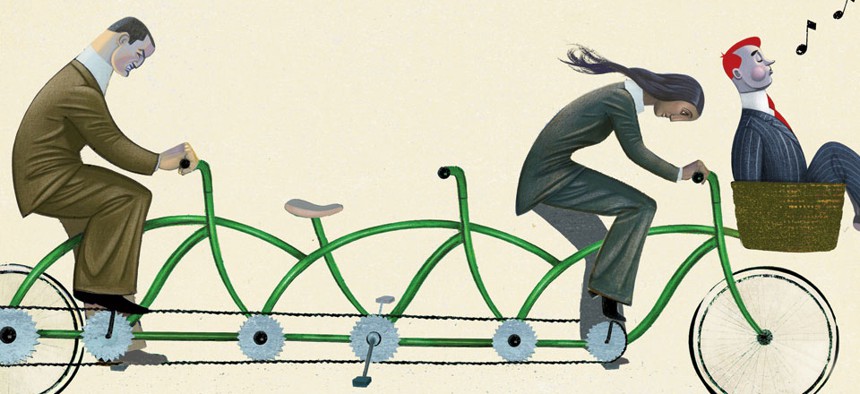

Jon Krause

The Science of Slackers

How to get your colleagues to carry their weight.

When people come together in groups, there’s usually at least one member who slacks off. Whether you call it shirking or social loafing, it’s a major source of misery and prevents teams from achieving their potential.

It turns out the worst offenders are American men. When psychologists Steven Karau and Kipling Williams

analyzed 78 studies of free-riding in groups, they found that it was more common among men than women, and in Western than Eastern countries. On

average, American men tend to be more individualistic and less group-oriented than women and non-Americans.

When you’re stuck working with free-riders, how can you motivate them to step up to the plate? Karau and Williams identified a series of factors that encourage people to contribute their fair share.

Make the task more meaningful

People often slack off when they don’t feel that the task matters. When they recognize the importance of their efforts, they tend to work harder and smarter.

Years ago, colleagues and I studied call center employees who were raising money for a university, but felt that their individual efforts were just a drop in the bucket. To highlight the significance of the task, we invited a scholarship student who benefited from their work to speak with the callers. It was a randomized, controlled experiment: some of the callers heard about how their fundraising had improved the student’s life, whereas others didn’t. After a five-minute interaction with a scholarship student, the average caller spent 142 percent more minutes on the phone and raised 171 percent more revenue per week. The largest effect was on the free-riders, who quadrupled their weekly donation rates.

Show them what others are doing

Sometimes people simply don’t realize that they’re doing less than the norm. In this situation, the key is to help them compare their contributions against their peers’ efforts. A research team including the psychologist Robert

Cialdini, for example, showed that people conserve more energy when they can see how much their neighbors are conserving. When the company

Opower randomly assigned roughly half of 600,000 households to receive home energy reports that included neighbors’ usage, conservation skyrocketed, especially by those who were wasting a lot of energy.

Shrink the group

When working in a large team, it’s easy to question whether individual efforts really matter.

In a famous experiment decades ago, psychologists invited people to make as much noise as possible in groups, in pairs and alone. In groups of six, each individual averaged only 40 percent capacity. As fewer members were involved, people made less noise in total, but each member’s average contribution increased. Individual contributions increased to 51 percent capacity when the group was reduced from six members to four, and spiked to 71 percent capacity when people worked with just one colleague. The smaller the group, the more responsible each member feels for contributing.

Assign unique responsibilities

Many groups balloon in size because people are trying to be polite—they want to include everyone and offend no one. In these cases, it’s not difficult to shrink the group, but in other situations, the group is large because the task requires many members. In those contexts, the easiest way to boost effort is to make sure each group member has a distinctive role. Karau and Williams found that free-riding was common when people saw their contributions as redundant. If each member is delivering something different, it can’t be taken for granted that someone else will cover your tracks.

Make individual inputs visible

When it’s impossible to see who’s doing what, people can hide in the crowd. Once everyone knows what each group member is adding, no one wants to be seen as a slacker. In an experiment with brainstorming groups, when people submitted ideas with their names attached, they contributed 26 percent more ideas than when they submitted anonymously.

Build a stronger relationship

If it’s challenging to change the task or the results, it could be time to work on the relationship. People don’t worry much about letting down strangers and acquaintances, but they feel guilty about leaving their friends in the lurch. Karau and Williams demonstrated that people stopped slacking when they worked with colleagues they liked or respected. If you can establish a personal connection, teammates often become more committed and dedicated.

If all else fails, ask for advice

Sometimes it’s useful to go right to the source. What if you approached a slacker and said the following? “I’m trying to get some members of this team to contribute more, and I wanted to seek your guidance on how to do that.” Research by professor Katie Liljenquist reveals that when you ask for advice, you flatter your colleagues and encourage them to look at the problem from your perspective. Having walked a mile in your shoes, they’re more likely to advocate for your interests. They might start adding more value themselves, or lobby colleagues to pick up the slack. At minimum, you’ll get some good ideas from the viewpoint of people who aren’t as motivated as you are.

Adam Grant is a professor at the

University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and author of Give and Take:

A Revolutionary Approach to Success (Viking Adult, 2013).

NEXT STORY: A Glass Half Full