Obama talks to troops at Bagram Air Field in 2014. Staff Sgt. Evelyn Chavez/Defense Department file photo

In his recent cover story for The Atlantic , Jeffrey Goldberg notes that when Barack Obama first entered the White House, with George W. Bush’s long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq ongoing, “he was not seeking new dragons to slay.” Just the opposite: He fit the mold, Goldberg argues, of a “retrenchment president” elected to scale back America’s commitments overseas and shift responsibilities to allies. But you could be forgiven for thinking the dragons have stubbornly remained, and even multiplied, on Obama’s watch.

To cite just some recent examples: In October, the president authorized the first sustained deployment of U.S. special-operations forces to Syria to complement his air campaign against the Islamic State. In January, reports emerged that the Obama administration was rethinking its troop drawdown in Afghanistan, given the deteriorating security situation there, and considering sending more troops to Iraq and Syria. The next month, Obama released a defense budget that included an increase of $2.5 billion over the previous year to expand the fight with ISIS to North and West Africa, and billions more for sending heavy weapons, armored vehicles, and other equipment to Eastern and Central Europe to counter Russian aggression. In the past several weeks alone, we’ve learned of Pentagon plans to dispatch military advisers to Nigeria against the jihadist group Boko Haram and to launch an aerial offensive in Libya against the Islamic State. U.S. bombing raids recently killed 150 suspected militants in Somalia and over 40 in Libya . By one measure, in fact, the U.S. military is now actively engaged in more countries than when Obama took office.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Although Obama never presented himself as a pacifist candidate , his 2007-2008 presidential campaign was predicated in part on the promise to end the war in Iraq and properly prosecute the war in Afghanistan. In March 2008, he declared of Iraq, “When I am commander in chief, I will set a new goal on day one: I will end this war.” Later that year, he listed his first two priorities for making America safer as “ending the war in Iraq responsibly” and “finishing the fight against al-Qaeda and the Taliban.” The president also promised a foreign policy that relied more on diplomacy and less on military might in his first inaugural address , telling his audience that “our power grows through its prudent use; our security emanates from the justness of our cause, the force of our example, the tempering qualities of humility and restraint.” Well before the tumult of the Arab Spring and its aftermath, Obama famously offered to extend a hand to those willing to unclench their fist.

In many ways, Obama has kept his word. He ended Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom —the combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, respectively, that Bush bequeathed to him—and drastically reduced U.S. troop levels from their peaks in both countries . In the midst of the Arab Spring, the president led a limited military campaign against Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi with the support of the United Nations and a multinational coalition. He has been reluctant to intervene in Syria’s civil war in any significant way despite intense pressure to do so from both inside and outside his administration. In 2013, Obama announced his intention to shift the United States away from “a perpetual wartime footing.” He said, “Our systematic effort to dismantle terrorist organizations must continue. But this war, like all wars, must end.” And Obama has repeatedly shown his commitment to diplomacy by reestablishing relations with Burma and Cuba , and by striking a nuclear deal with Iran .

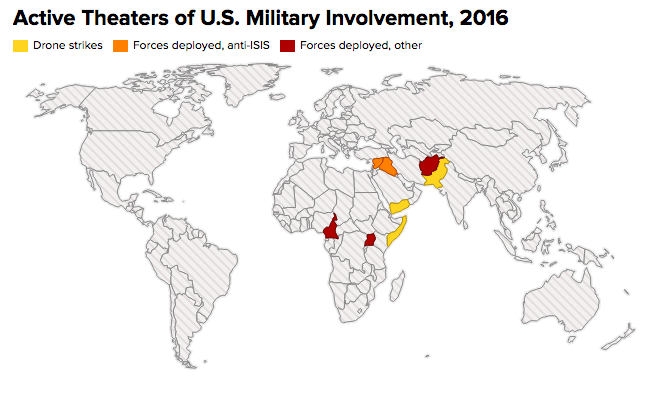

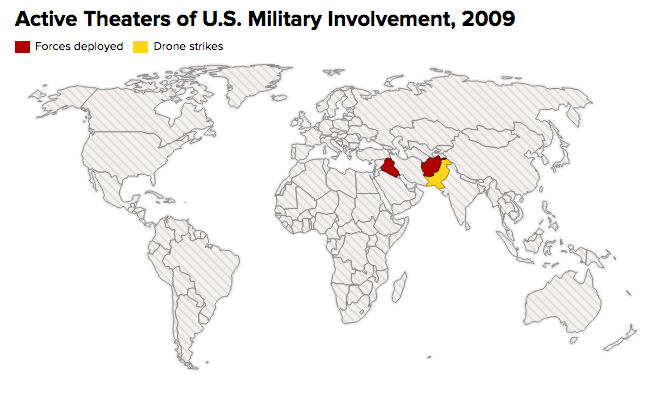

And yet while America’s military footprint abroad is fainter today than when Obama took office, it’s also more dispersed. Not counting the probable expansion of the anti-ISIS campaign to Libya and other parts of Africa in the near future, the U.S. military is, by my reckoning, involved in more countries now than when Obama took office in 2009, albeit to varying degrees.

To be fair, defining U.S. “military involvement” is tricky, partly because there are many levels of engagement between no military involvement and full-scale invasion, and partly because so much of the U.S.’s military activity is done from the shadows. That’s why, in consultation with Anthony Cordesman at Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and Chris Harmer at the Institute for the Study of War, I’ve limited the definition of military involvement to countries that the United States is consistently bombing (overtly or covertly); where regular U.S. troops are engaged in combat; or where regular U.S. troops are providing intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in support of another military force that is engaged in combat. By that definition, the U.S. is currently fighting in roughly eight countries. (For sanity’s sake, my definition excludes special-operations forces; Ken McGraw, a spokesman for U.S. Special Operations Command, or SOCOM, told me in early February that special-operations personnel were deployed in 82 countries that week alone.)

These eight theaters encompass the continuing conflict in Afghanistan; drone wars in Pakistan , Somalia , and Yemen ; the anti-ISIS campaign in Iraq and Syria; and two advise-and-assist missions—one against Boko Haram , which is at least nominally affiliated with ISIS , in Cameroon, and another against Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda and nearby countries. That’s more than double the countries that fit my definition of U.S. military involvement in January 2009, when it encompassed ongoing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and an incipient drone war in Pakistan.

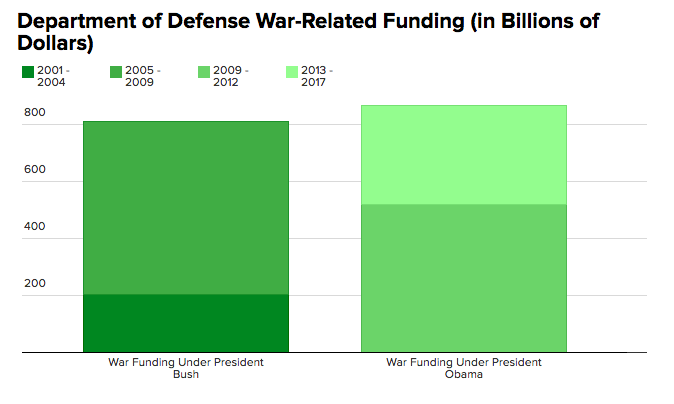

Other metrics also suggest that the country has not abandoned its wartime footing under Obama. As a candidate, Obama argued that the Iraq War represented an exorbitant cost for the American people. Over the course of his presidency, though, the U.S. military will have allocated more money to war-related initiatives than it did under Bush: $866 billion under Obama compared with $811 billion under Bush. (Measuring war-related spending is also tricky, but the Defense Department’s “Green Book” offers the most reliable figures, according to Todd Harrison at CSIS. These figures don’t account for war-related funding within the State Department or USAID.) It’s worth noting that annual expenses have decreased in recent years with the ending of the war in Iraq and the de-escalation of the war in Afghanistan.

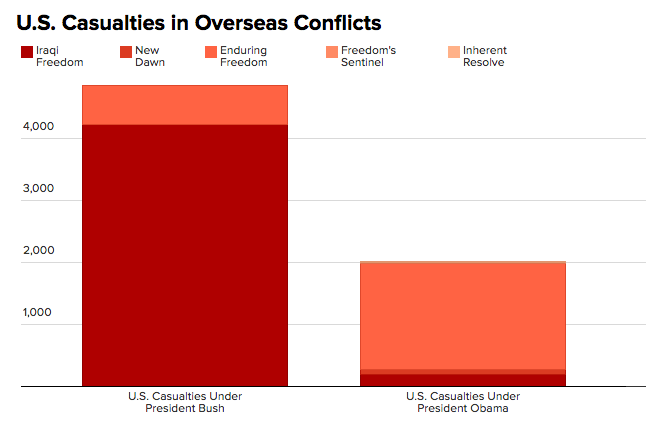

In one important way, Obama has made good on his pledge to extract America from war and make Americans safer: The number of U.S. troop casualties under Obama is significantly below the tally under Bush. During the Bush administration, the Iraq War alone cost 4,229 American lives; the Afghanistan War claimed 635 more. Although casualties in Afghanistan increased on Obama’s watch, largely due to a surge in troop levels in Obama’s first term, the president has presided over a nearly 60-percent decline in total number of soldiers lost. In the 20 months since the United States began its military campaign against ISIS, there have only been 15 U.S. casualties , with the most recent occurring just over a week ago .

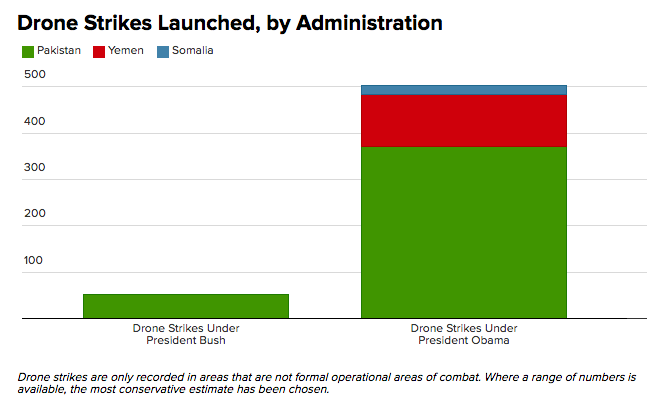

This decline in casualties has much to do with Obama’s marked preference for using air strikes or special-operations forces over large numbers of infantry. As Goldberg noted , Obama has “become the most successful terrorist-hunter in the history of the presidency.” Whereas Bush launched 51 drone strikes against suspected terrorists in Pakistan, for example, Obama has unleashed 372, according to data gathered by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism . (The frequency of such strikes has been declining since 2010, however.) According to the same data set, Obama has authorized at least 112 strikes in Yemen and 19 in Somalia . Bush launched one solitary strike in Yemen during his entire presidency.

Obama has also embraced special-operations forces. In fiscal year 2014, U.S. special-operations forces deployed to 133 countries, or roughly 70 percent of the entire world, The Nation reports. General Joseph Votel, the commander of SOCOM, has said , “The command is at its absolute zenith. And it is indeed a golden age for special operations.” The size of SOCOM has expanded by almost 25 percent since Obama took office, increasing from 55,800 people to 69,700, according to McGraw at SOCOM.

In other words: The dragons persist, but now the dragon-slayers tend to operate in the air—or in the shadows.