HELD BACK

Why the government struggles so much with job one: hiring.

By Kellie Lunney | Illustrations by Will Mullery

Amid fruit-filled martini glasses—sans alcohol—a group of government workers gathered around several tables in November in an elegant Washington hotel and discussed federal hiring with gusto. Dominating the talk was the Pathways program and veterans’ preference, two authorities the government can tap to hire more millennials and veterans into the civil service. Neither hiring mechanism is new. But both consumed the energy at the “Rethinking People Strategies in Government” conference sponsored by FedInsider and the George Washington University.

One table included employees from various agencies: the General Services Administration, the Navy and the departments of Health and Human Services and Housing and Urban Development. One participant described the Pathways program as “horrible.” As for veterans’ preference, there was praise for its intent, but frustration over how it’s applied and speculation over whether it sometimes results in poor hires or favoritism. It was a surprisingly candid breakfast conversation about subjects that quickly can become politically sensitive, especially when it’s about who is getting which jobs. But it wasn’t until the Q&A after a keynote speech by Ann Marie Habershaw, chief of staff and external affairs director at the Office of Personnel Management, that the discussion revealed some larger truths about the challenges of federal hiring.

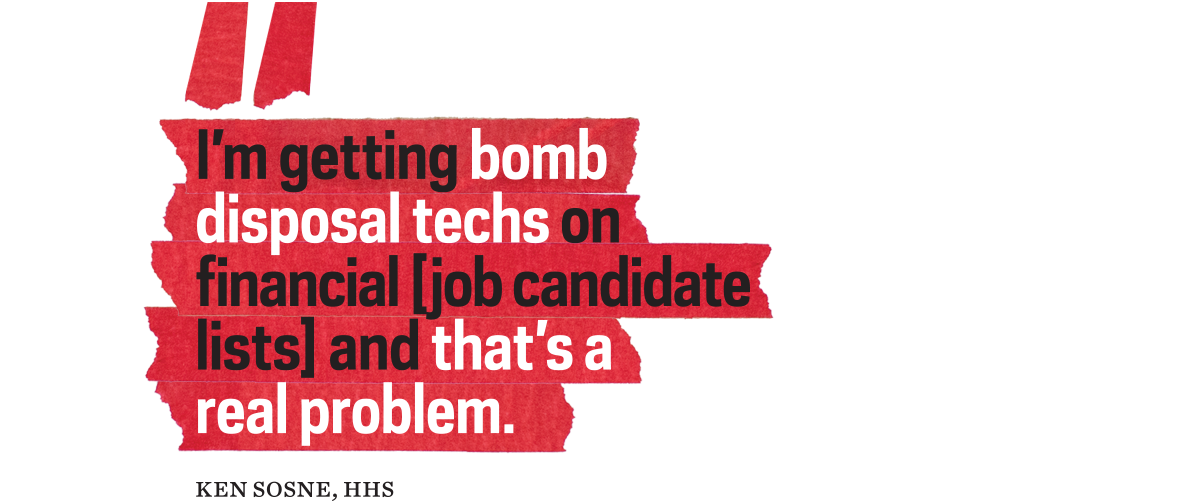

Ken Sosne, a divisional director and hiring manager with HHS’ Administration for Children and Families, posed this question to Habershaw in front of the room:

“The Pathways program, the way it is structured right now is actually not very helpful, because you are pushing the veterans’ preference issues, but we’re not getting the pool of candidates that we need. The question I had was, how do you find the balance between what I—I mean, vets are very valuable, there is no question about it—but what I see is a myopic view of saying ‘just vets only’ because that’s what we’re getting. How do we find the right balance so we can bypass vets and get the pool? I’m looking at the public pool, and I want to favor vets, but I’m getting bomb disposal techs on financial [job candidate lists], and that’s a real problem.”

Habershaw responded:

“You know, Pathways is a tough one because it’s a new program that was made because of challenges with the previous [program]. One of the things I’ve been trying to focus on is more the public notice issue, to really kind of give agencies more flexibility in how they recruit for Pathways. The veterans’ preference is a different challenge. I don’t know why you are getting explosives experts for financial positions. I don’t know that I can solve that question but what I found is that there is a real misunderstanding about how to use and apply veterans’ preference, and that’s what we are hearing from people, and it’s figuring out how we clear up those issues. That is definitely a challenge.”

Then Tania Allen, the veterans’ employment program manager at the Environmental Protection Agency, spoke up to respond to Sosne’s question:

“When I consult with our hiring managers and they have issues like that, if you don’t have a strong vacancy announcement, if you don’t view your HR specialist as a consultant prior to posting the vacancy announcements, then you are going to get people who are not qualified for your job. The veterans that are qualifying for the positions are qualifying based on the questions in the vacancy announcement. If you have a strong vacancy announcement that is addressing the specific skills that you’re seeking to fill that position, then you’ll only get those that are qualified. If they happen to be veterans, then they happen to be veterans, but they’re going to be the most qualified people.”

This exchange encapsulates the hiring challenges the federal government faces: Highly complex regulations, confusion over how to apply the rules to hire the most talented applicants while also preserving fairness and diversity, disconnect among the major players, and head-scratching over how to fix it. At the root is this question: If the federal government can’t figure out how to hire the right people and be a model workforce for the rest of the country, then how is it supposed to effectively deliver goods and services, protect America, and solve our most pressing policy problems? When you think about it that way, federal hiring suddenly becomes a lot more interesting.

Knot Working

“We are drilling down in agencies to find the knots in the hiring process, and to untie them,” said OPM Director Katherine Archuleta in a May 2014 speech to federal employees.

It turns out there are a lot of knots.

USAJobs, the government’s online warehouse of job vacancies, is still difficult to navigate and lacks sophisticated search capabilities to help applicants find positions that meet their interests and qualifications. Recruiting and hiring tools, including veterans’ preference, Pathways, and the prestigious Presidential Management Fellows program, are innovative. But they’ve become encased in layers of complicated rules that most hiring managers and even some HR staff don’t understand or use properly. Job descriptions typically exceed 1,500 words, and many of them are barely comprehensible, at least to the uninitiated. Agencies are supposed to get new hires onboard within 80 days, but for some jobs, it can take several months.

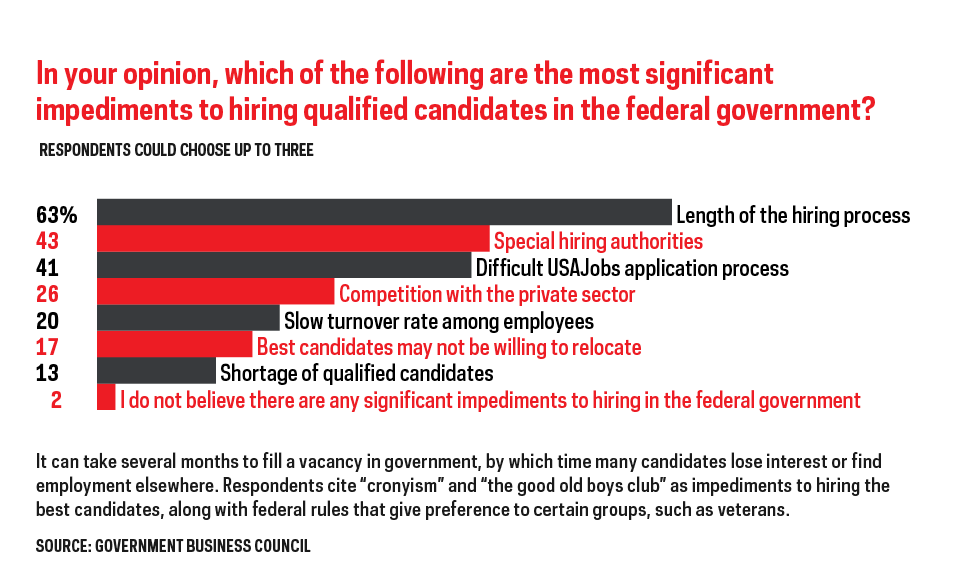

In fact, all three of those issues—USAJobs applications, special hiring authorities and the length of the hiring process—were cited as the most significant impediments to hiring by federal employees who responded last fall to a survey conducted by Government Business Council, the research arm of Government Executive Media Group.

Some things have improved since OPM launched a major hiring reform effort in 2010: better and more frequent communication between job applicants and agencies, more targeted outreach to specific groups such as millennials and veterans, the elimination of lengthy knowledge, skills and abilities essays in favor of a resume-based application process. The government also chucked the “rule of three” (though technically it remains on the books) in the competitive civil service, under which hiring managers made their selections from a list of the top three candidates and eligible vets received an extra 5 to 10 points. Replacing it was the “category rating” system, aimed at increasing the number of qualified candidates that supervisors can choose from, while also preserving veterans’ preference.

Jeffrey Neal, a former chief human capital officer at the Homeland Security Department and the Defense Logistics Agency, frequently writes about federal hiring. This is how Neal, now founder of ChiefHRO.com and senior vice president of ICF International, explained category rating in an Oct. 16 piece for Federal News Radio:

“With category rating, applicants are placed in two or more groups. Applicants who are eligible for veteran preference are listed ahead of individuals who are not preference eligibles. With the exception of scientific and professional positions at GS-9 of the General Schedule (equivalent or higher), qualified preference-eligibles who have a compensable service-connected disability of 10 percent or are listed in the highest quality category. Selecting officials may select any applicant in the highest quality category.”

That’s one of the more succinct explanations of category rating out there, and it still makes your head hurt. And to make matters even more complicated, category rating is used in competitive hiring, which is just one way the government can hire people. There’s the excepted service, which covers certain occupations requiring specialized skills, such as lawyers. Jobs in the excepted service, unlike those in the competitive service, don’t have to be posted on USAJobs and are not open to everyone. Then there’s direct hire authority for certain jobs that agencies must fill quickly due to a shortage of workers with critical skills—think nurses and employees in information technology. And there’s the Veterans’ Recruitment Appointment, which allows agencies to hire eligible vets for certain jobs without competition. That falls under the umbrella of “veterans’ preference” but is actually separate from the veterans’ preference scoring system used in competitive hiring. Finally, the Pathways program includes three tracks: current students, recent graduates and Presidential Management Fellows. Participants are classified under Schedule D within the excepted service, and each Pathways program honors veterans’ preference.

That’s just a sampling of how applicants can get their foot in the door. And just because flexibilities exist doesn’t mean they are easy to understand or apply properly.

To be fair, the federal government is the largest employer in the world, with roughly 2 million civilian employees all over the globe. It’s unreasonable to expect a seamless HR operation at this scale. The merit principles it embodies are noble but cumbersome. A private sector manager can throw 30 job applications in the trash without even looking at them. Anyone who does that in the federal government risks serious legal trouble.

The reality is that today’s federal hiring process breeds fear in HR staff and hiring managers, distrust among federal employees who perceive the process is rigged, and frustration in everyone.

“In many ways, it’s the most important thing the government does,” says Janice Lachance, OPM director during the Clinton administration. “The government is not making widgets. This is a knowledge-based workforce. The government’s effectiveness is dependent on the people who are doing the work.”

As the federal agency that sets governmentwide HR policy and oversees everything from hiring to retiring, OPM has a challenging mission. Hiring traditionally has been viewed as a “back office” function, though that attitude is changing. Federal hiring reform began in earnest under Archuleta’s predecessor, John Berry, now the U.S. ambassador to Australia. But OPM still struggles to play its role effectively, partly because it historically has lacked clout and authority within the executive branch.

OPM and Archuleta know government has to do a better job of branding and pitching itself—on social media and on college campuses—to engage a younger audience. The agency also knows that HR staff throughout government are stymied by ever-dwindling resources, arcane rules and complex hiring processes. OPM officials understand the need to make the hiring process simpler and faster, but that goal has to be balanced against the virtues of fairness and inclusion, not to mention the priorities of the administration in power.

“The talent in that agency is staggering, and their ability to work with other agencies is unsurpassed,” Lachance says. But those other agencies, starting with the leadership, have to make a commitment to human resources, both the system and the people, says the former OPM director. “OPM can’t impose that kind of culture on other departments. They can send out guidelines, help pass legislation, but they can’t enforce a culture.”

Kim Holden, OPM’s deputy associate director for recruitment and hiring, says the agency continues to provide regular in-person and online training and resources to hiring managers and HR professionals on a range of topics. In July, OPM began collecting data and feedback from nearly a dozen focus groups, including students, seniors, current federal employees and veterans, on how to improve USAJobs. That research will form the basis for the next version of the hiring portal, and it could be a massive makeover. The agency wants to “address root causes rather than fix the symptoms, and what people typically complain about,” Holden says.

Neal says OPM has an “incredible amount of responsibility” overseeing HR policy and writing regulations, in addition to its roles in the security clearance process and administering the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. But the agency could do more, especially in areas where HR policy is not enshrined in existing statute. “What is law is not very much,” Neal says.

The GBC survey asked respondents involved in the hiring process at their agencies to rate the support received from their own HR staff and OPM during the hiring process. On a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest score, respondents on average gave both groups low marks: 2.9 for their agency’s HR operation, and 2.0 for OPM. Even if OPM is making a solid effort, something isn’t translating.

Moving in Lockstep

The relationship between OPM and federal HR staff across government is an important one. Perhaps even more vital, however, is the one inside an agency between HR specialists and hiring managers.

“Hiring managers should be in lockstep with HR,” says Liz Joyce, a senior director in the government human capital practice at CEB and a former federal employee with experience in hiring. When HR and program supervisors work closely throughout the hiring process, communicating at every stage, it increases the likelihood that the system works the way it should: fairly, as expeditiously as possible, and yielding the most qualified candidates for the job. The key to that is doing much of the work up front, creating the right job description or “recruitment package” that is targeted but not overly prescriptive, and broad without being so generic that you’ve got, say, explosives experts applying for financial analyst positions.

“What we’ve seen across managers, and I was guilty of this as well, they are almost sourcing a unicorn,” Joyce says. Sourcing is HR-speak for proactively seeking out qualified candidates for current or future positions. “They could be looking at too technical or specialized of a skill set, or they are looking for too many competencies or experiences creating this kind of applicant that we can’t actually find.” Joyce says HR should help program managers articulate which competencies matter most. In CEB’s research of public and private sector organizations, it found that “a lot of qualified candidates were screened out because of the manager’s technical expertise requirements. So people who could be good fits don’t end up even getting on the most qualified lists for managers to look for because their expectations are too high.”

Towanda Brooks, deputy chief human capital officer at HUD, led a major hiring blitz last year at the department. HUD hired 1,036 people in fiscal 2014, a combination of internal and external candidates through competitive and noncompetitive hiring, from more than 120,000 job applications. The department did 35 percent of its hiring in September alone. Communication, transparency and strategic planning from the beginning helped HUD accomplish its goal, Brooks says. She and Michael Anderson, the department’s chief human capital officer, briefed senior agency leaders from across HUD every week on the hiring initiative. Brooks, in turn, held weekly meetings with HR specialists and hiring managers—the people on the ground—to see what was working and what wasn’t.

“That was one of the things that, early on in the process, really helped, because a lot of times the data between the human capital office and the program office was slightly off,” says Brooks, who has more than two decades of experience in federal HR at several agencies, including the departments of Commerce, Energy and Homeland Security. So HUD developed a database to track hiring and identify bottlenecks. For instance, HR staff and hiring managers expressed concern that the security clearance process, which also involves OPM and the FBI, could derail the timeline for getting people onboard. But they worked through those issues ahead of time, Brooks says, by ensuring the office dealing with that part of the hiring process had enough staff to handle the influx of new people and documentation.

“I would say that there was a lot of visibility throughout the process,” Brooks says. “Everybody knew if the HR specialists were having trouble doing qualifications, or if the managers were stumbling a little bit getting interviews done, and other people would come in and help.”

HUD also did outreach to different communities, including veterans, and used various hiring mechanisms available to attract and hire a diverse group of people. Brooks said they hired Peace Corps volunteers and Presidential Management Fellows—the latter being a priority of then-HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan. To Brooks, the fact that the hiring initiative had different stakeholders and was a priority for the department’s leadership helped elevate it to a level where lots of people had a vested interest in its success.

“For me, hiring used to be a rote process,” Brooks says. “It was looked at as, HR was responsible for everything.” But over time and with hiring reform, it feels more like a human capital initiative and that hiring is the agency’s function, she says. “There’s more ownership in the agency to get it done.”

Questions of Fairness

The Obama administration has made it clear it wants the federal government to effectively recruit the next generation of employees and hire more veterans to create a diverse, model workforce that can tackle the challenges of the modern era.

In theory, this makes sense—from a business standpoint as well as a public service one. But as with so many things in government, it becomes complicated in practice. Federal employees must carry out an administration’s priorities with a limited amount of resources in a specific time frame while adhering to lots of rules and laws.

Pathways, for example, grew out of the old Federal Career Intern Program, which was scrapped in 2010 after the Merit Systems Protection Board found it violated veterans’ preference laws. Two preference-eligible vets claimed the FCIP did not allow them to compete fairly for government jobs. So the government created Pathways, which requires a public notification process for jobs so that any student or recent graduate is aware of opportunities throughout government. Under the old system, agencies could work with universities and colleges they had partnerships with to select students. But now, the process is more transparent and open to more people: single mothers who go back to school for their degrees, or veterans taking advantage of the G.I. Bill, for example. The number of applications has spiked as a result—as has confusion about what agencies can and cannot do when it comes to hiring through Pathways.

Good government groups are trying to educate agencies, universities and students about Pathways and dispel some misconceptions about it, ranging from when to apply vets’ preference to whether agencies can target specific academic institutions. “The recruitment and hiring system, both for pre-career and for midcareer employees, is seriously limping and federal internship programs are just plain broken,” Shelley Metzenbaum, president of one such group, the Volcker Alliance, told the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee in March 2014.

OPM plans to do more training on Pathways over the course of 2015, Holden says. “Overall, all the agencies want this to be a successful program.”

But even after intern and student programs have been opened to a wider applicant pool, a large percentage of federal employees and applicants think the current hiring process favors certain candidates, or is somehow rigged. For instance, 68 percent of GBC survey respondents said veterans’ preference sometimes prevents the best candidate from getting the job, while 25 percent disagreed.

Vets’ preference in federal hiring, in some form, has been around since the 19th century, but it has evolved into a complicated patchwork of laws and hiring authorities for vets and their spouses. “There are so many factors about the person applying, the position for which he or she is applying, the authorities being used, and the agency in which the positions exist, that the system is beyond unwieldy,” MSPB wrote in an August 2014 report on veterans’ preference laws. That study surveyed federal employees, finding that 4.5 percent of workers said an official in their agency knowingly violated veterans’ preference laws, and 6.5 percent “inappropriately favored a veteran.” Those were perceptions, not actual findings of misconduct.

Neal says it’s true that a certain amount of favoritism for vets is built into the system. A veteran with a disability who is qualified for a job, but not as qualified as a nonveteran, is likely to get the job because of preference regulations. But as a country we’ve decided that we are going to allow for that, and “people need to just deal with it,” Neal says.

“Hiring a qualified person who might be a compensably disabled veteran over a more qualified person who may not be a veteran at all is a public policy decision. Congress has backed that decision. The president has backed that decision. Every president in recent memory has backed that decision. Most people who don’t want to go get shot at themselves back that decision until they apply for a job and then they say, ‘Why did Fred get preference over me?’ ”

Neal advises agencies to actively recruit highly qualified veterans for jobs where they anticipate a lot of interest from vets. “Then you don’t have to worry about having a lesser-qualified veteran because you’ve got highly qualified veterans on your list.”

The notion of favoritism, real or imagined, tends to crop up over internal promotions and lateral movements within the government more than with new hires, says CEB’s Joyce.

“The infrastructure is in place to make sure everyone is competitive, but if it comes down to, there is a person that the hiring manager wants to hire and they are qualified for the position and they are not blocked by somebody else—like a veteran—they can make that selection as long as they are on the best qualified list,” Joyce says. People might think that’s unfair, but it’s perfectly legitimate, as long as the process isn’t being manipulated or “cooked” as Neal calls it, with a certain person in mind.

There have been instances where hiring managers have “gamed the system” and drafted position descriptions to fit a particular person, and it’s hard for HR professionals to catch it, Joyce says. “But as HR is more involved in the process, and hiring managers work with HR more, that would resolve itself.”

Kellie Lunney covers federal pay and benefits issues, the budget process and financial management. After starting her career in journalism at Government Executive in 2000, she returned in 2008 after four years at sister publication National Journal writing profiles of influential Washingtonians. In 2006, she received a fellowship at the Ohio State University through the Kiplinger Public Affairs in Journalism program, where she worked on a project that looked at rebuilding affordable housing in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina. She has appeared on C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, NPR and Feature Story News, where she participated in a weekly radio roundtable on the 2008 presidential campaign. In the late 1990s, she worked at the Housing and Urban Development Department as a career employee. She is a graduate of Colgate University.