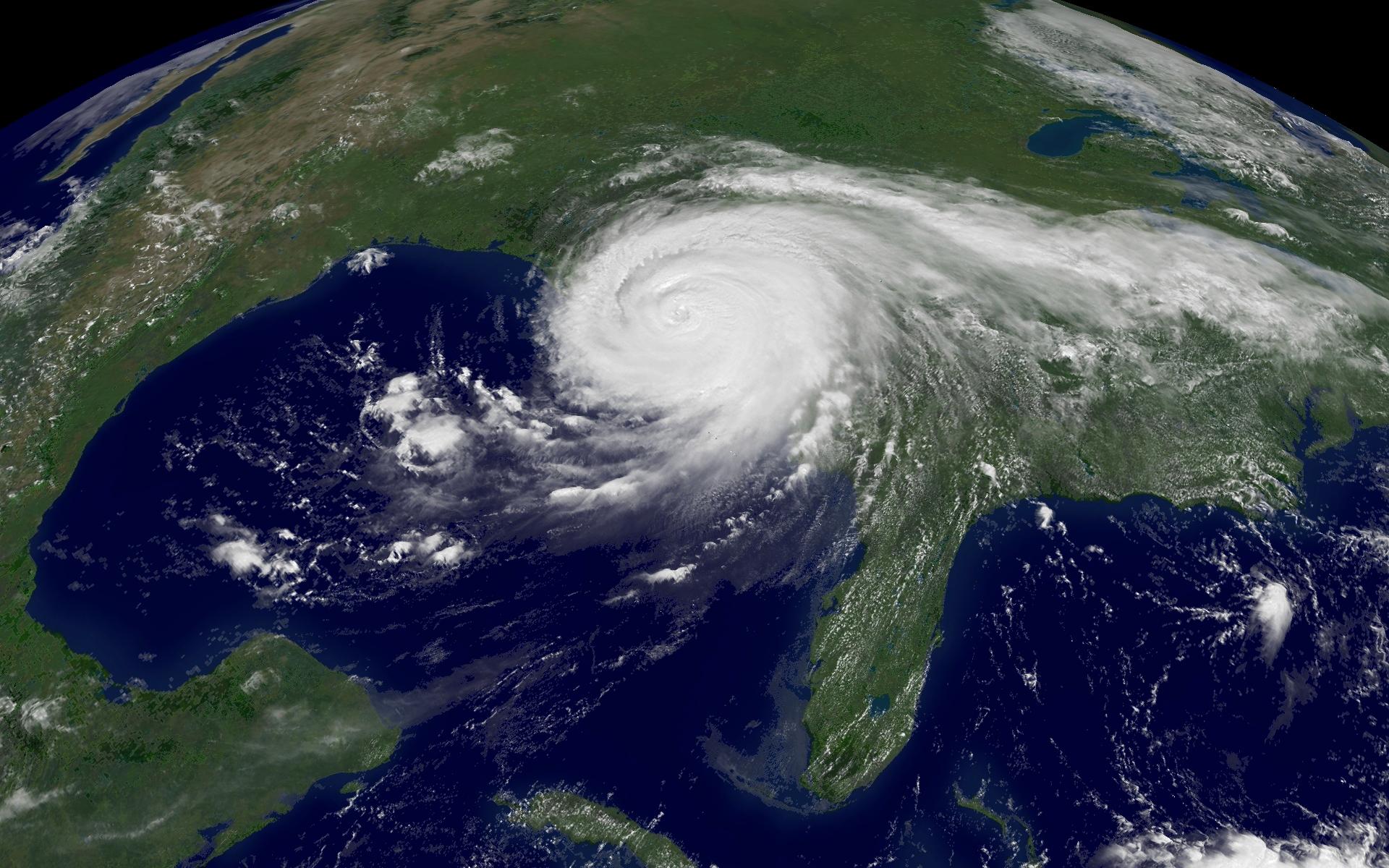

Some disasters you see coming. Hurricane Katrina was one of them.

In New Orleans, people had been bracing for The Big One for decades. The city sits in a bowl, surrounded by water kept at bay by canals and levees constructed to hold back Lake Pontchartrain to the north and the Mississippi River to the south as it snakes through the city en route to the Gulf of Mexico. In summer 2004, the Federal Emergency Management Agency brought together nearly 300 people from all levels of government to simulate the city’s response to a slow-moving Category 3 hurricane — the hypothetical Hurricane Pam. The results were not encouraging. A year later, officials found themselves grappling with the all-too-real Hurricane Katrina.

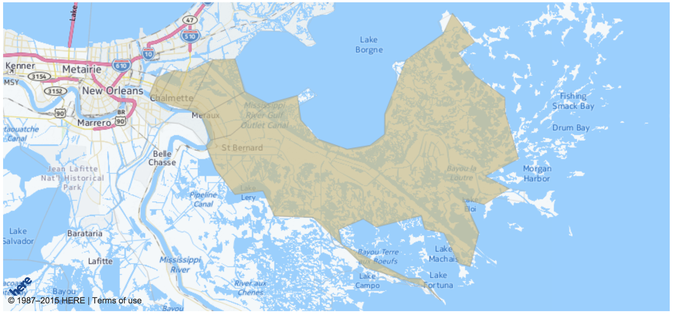

Katrina’s destruction 10 years ago this summer has been well-documented: Nearly 2,000 lives lost in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida and Georgia. Entire communities wiped off the Gulf Coast. Hundreds of thousands of people displaced. Four levees breached in New Orleans after the storm, culminating in floodwaters of 15 to 20 feet covering 80 percent of the city.

Katrina was a natural disaster that morphed into a manmade catastrophe.

The failure of government at every level — federal, state and local — to respond quickly and decisively to Katrina is indisputable. And a decade later, still heartbreaking. But the disaster also gave rise to the heroism of countless ordinary citizens, first responders and government workers in the face of chaos and unremitting loss.

To mark the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Government Executive talked to 10 people who witnessed the storm and its aftermath from their roles in government. Our goal here is not to provide comprehensive coverage of the event, or a full analysis of what went wrong. It’s simply to offer what we hope are some valuable insights into the extraordinary limits and capabilities of

government.

The Responders

Chief of staff of the U.S. Coast Guard

Director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency

Business agent for the National Association of Letter Carriers

Executive director of the Biloxi Housing Authority in Mississippi

Director of the public health preparedness program at RAND

Director of the National Hurricane Center

Leader of the first U.S. Public Health Service team dispatched to the region

Federal Housing Administration commissioner, Housing and Urban Development Department

Director of civil works at the Army Corps of Engineers

Deputy director of the National Finance Center

Forecast and Missed Opportunities

On Tuesday, Aug. 23, 2005, the National Hurricane Center in Miami issues an advisory about a tropical depression forming over the Bahamas, 350 miles east of Miami. By Wednesday, the depression strengthens into a tropical storm. Katrina is born.

Max Mayfield: One of the senators, I think Sen. Nelson of Florida, asked me when I first became concerned for New Orleans, and I said “about 60 years ago.” Most people that know anything about hurricanes know that southeast Louisiana, including New Orleans, is extremely vulnerable to hurricanes and especially storm surge.

Thursday, August 25

Michael Brown: As the cone got more narrow by Thursday, New Orleans was the target. I can tell you that all eight floors of FEMA on C Street [in Washington], and every region in the country, was on full alert because we were exceptionally worried it would be Hurricane Pam come to life. We know for certain it’s headed toward New Orleans. We know internally we have a dysfunctional state . . . Now, I love [Louisiana Governor] Kathleen Blanco to death, she’s a nice woman. But she didn’t have the kind of system that allows quick decisions.

One of the senators asked me when I first became concerned for New Orleans, and I said 'about 60 years ago.'Max Mayfield, director of the National Hurricane Center

Friday, August 26

Katrina moves across Florida, heading for the Gulf of Mexico, where National Hurricane Center officials warn it will gather strength before moving ashore, most likely near New Orleans. The National Finance Center, which is located in the city and processes payroll for about 650,000 civilian federal employees, declares a state of emergency, triggering its continuity of operations and IT disaster recovery plans; it completes its work on the next payroll cycle to ensure people are paid on time. The Postal Service partners with the Social Security Administration and other agencies to establish distribution centers to disburse benefit checks, knowing mail delivery will be disrupted. In Washington, leaders at the U.S. Public Health Service discuss what potentially will be a public health disaster. Many Gulf Coast businesses close and urge employees to leave. Many local officials declare mandatory evacuations, but not New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin.

Brown: We were told they will use the Superdome [in New Orleans] as shelter of last resort. I went ballistic. I’m sitting with a report saying the Superdome is the bottom of the fishbowl. If levees are breached, the engineer’s report showed it can’t withstand a Category 3, let alone a 4 or 5. Its roof will be ripped apart, and there will be no power. We said that’s a mistake, and they shouldn’t do it, we need to evacuate. It just falls on deaf ears . . . I just lose my temper. I’ve got Amtrak, United, American, Southwest and Delta airlines, and Greyhound, who all have assets — planes at Louis Armstrong Airport, or the New Orleans train station, buses — they have all agreed to take people out. All people have to do is show up and they will help evacuate the city. So I’m asking my staff, why the hell is there not a mandatory evacuation? . . . My staff said, “Well, Mr. Brown, there is a fight between the mayor and the governor,” and this is where I begin to understand, before leaving for Baton Rouge: This is going to be a snafu.

So I’m asking my staff, why the hell is there not a mandatory evacuation? . . . My staff said, 'Well, Mr. Brown, there is a fight between the mayor and the governor.'Michael Brown, director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency

Saturday, August 27

With Katrina gaining strength in the Gulf of Mexico, Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco tells the media, "I believe we are prepared. That's the one thing that I've always been able to brag about." Within hours, her confidence wanes: "I have determined that this incident is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capabilities of the state and affected local governments."

Mayfield: By sometime Saturday afternoon or evening, it was pretty obvious that people were not responding as we had hoped they would, especially New Orleans. So yeah, I called the governors of Louisiana and Mississippi, and actually Gov. Blanco in Louisiana, she’s the one who suggested I call Nagin directly. And I did. I guess he was at dinner. I left a message, and he called me back. I don’t remember exactly what I said but I know one thing I said to all three of those folks was that I wanted to be able to go to sleep that night knowing that I had done everything I could do to get the proper response. I’m sure I conveyed the possibility of a large loss of life if they didn’t respond appropriately.

Don Riley: I spent a good deal of Saturday on the phone with the Corps and with the Federal Emergency Management Agency. We briefed FEMA on our district experts’ plans to unwater New Orleans, to sector off the city. The forecast we gave was that if there were major breaches, it would take up to six months to get the water out of New Orleans.

Brown: The other part of my job is keeping the White House informed — that’s President Bush, Andy Card and Joe Hagin, the deputy chief of staff — explaining to them all what’s going on. Bush is in Crawford, Texas. I explained to Joe, “You gotta help me explain to the president, I really need him to call the mayor and use the bully pulpit.” Joe chuckled at me. “Seriously?” The president called me back while I’m in my Alexandria [Virginia] townhouse packing. Bush asked, “Brownie, what do you want me to do?” I said, “Mr. President, I need you to call the mayor and say we think it’s going to be really bad.” Bush does make the call. We’re well within the 72-hour period for mandatory evacuation, and the mayor decides to do a mandatory evacuation. But the storm is approaching landfall, we’re too late and a dollar short. The airlines had left, Amtrak had left, the buses had left. Except for the people still in New Orleans.

I sent some people into the community to find water and food and things like sleeping bags because we didn’t know where next we were goingCapt. Charles L. McGarvey, leader of the first U.S. Public Health Service team dispatched to the region

to sleep.

Sunday, August 28

In the Gulf of Mexico, Katrina grows into a Category 5 hurricane, with 175 mph winds, just 170 miles southeast of the mouth of the Mississippi.

Mayfield: We had a noon [telephone] briefing . . . and then Mike Brown said, “Thank you, Max, now I’d like to take you to Crawford, Texas, and introduce the president of the United States.” So, the president was on the line. I kind of figured he might be listening, but I didn’t know for sure. You know, [Bush] was engaged, and actually, even Mike Brown was engaged. [Brown] asked, “Isn’t the Superdome in a flood zone? What about the roof of the Superdome?” He was asking all the right questions. But that’s water under the bridge now.

Charles McGarvey: I was contacted prior to Hurricane Katrina coming ashore by one of the admirals at [Public Health Service] headquarters and we discussed the needs in the New Orleans area. I was in church that Sunday when he buzzed me on my pager. He said, “Pack your bags. We’re going to fly a group down there and set up a field hospital in the Superdome in New Orleans.” So I prepared my equipment and got directions to meet up with my group at Dulles Airport [outside Washington] at one of the private terminals there that afternoon. There were about 37 in our group — physicians, nurses, therapists, pharmacists and some administrative individuals. We didn’t have very much time. We had not worked together and it was very important for people to get to know each other. While we were in flight, our orders were changed due to the chaos that was beginning to occur at the Superdome and how rapidly the storm was coming in. Our new orders were to fly into Jackson, Mississippi, and then travel to Baton Rouge to set up a field hospital.

Riley: I had planned to travel to St. Louis for a White House conference on the environment, but I told my wife I was canceling and going to Baton Rouge. I reported to the state Emergency Operations Center, where the Corps already had a lead team. The governor was there. We hunkered down that night and had to evacuate the Corps in the New Orleans District to get people out of the way of the storm. The district commander and civilian leaders stayed in their Emergency Operations Center, though they lost power and water right away. But at least we had a connection in the city . . . I would not use the word confusion, but we were scrambling to get information.

McGarvey: We arrived in Jackson around 11 p.m. We had to get special permission to come in there and we had to arrange for a series of rental vans to get our people and equipment to the Hilton. That whole process was something else. I anticipated that there may be some problems — Jackson was in the line of Katrina. We mustered before everyone went to bed and I said, “Look, there’s a really good chance we’re going to lose electricity, so you can’t depend on your phones or even your ability to get around the hotel — you’re going to have to get out your flashlights, you won’t be able to use the elevators, we’ll have to do what we can as far as food and water.” I sent some people into the community to find water and food and things like sleeping bags because we didn’t know where next we were going to sleep.

Landfall

Monday, August 29

Katrina makes landfall in both Mississippi and Louisiana as a slow-moving Category 3 hurricane.

Riley: On Monday morning we watched the storm surge 28 feet at its highest when it slammed up against the coast of Mississippi. Waveland, near Biloxi, was completely wiped off the map. They had no levees in Mississippi. Plaquemines Parish [Louisiana], which is like a 50-mile pier sticking out in the ocean, was swept over in both directions.

In New Orleans, four levees are breached: the 17th Street Canal levee; two along the London Avenue Canal and one on the Industrial Canal. Others are overtopped, causing 80 percent of the city to flood, with water rising almost 20 feet in parts.

Riley: We got word of the breach in the levees and floodwalls. The Corps district commander was trying to make his way but got stalled, taking high risks. Several civilian [employees] lost their homes in the process, but stayed at work like good soldiers. It’s hard to say it was a big shock, but it was one of those moments when you just knuckle down and try to figure out what happened. I took a Black Hawk helicopter overflight. It was astounding how much of New Orleans was underwater. I had a sickening feeling at all the damage, all those people suffering.

Two holes open in the Superdome roof around 9 a.m.

Brown: The storm hits, I’m sitting in a hotel room in Baton Rouge. We still have satellite connectivity, still getting reports. The Superdome is beginning to leak, floodwaters are rising around, the roof is ripped off, and people are beginning to flood into the Superdome. We get conflicting reports on breaches and toppings. We don’t know which is which. Typically in the midst of battle you get conflicting reports, until you can get your own eyes on the ground, you rely on conflicting reports and do the best you can.

Nicole Lurie: I sat there [in my home in Washington] watching the wind blow the roof off the [Superdome] and then more and more flooding, just being more and more concerned about what was likely to happen.

McGarvey: Katrina hit and the hotel lost power. The elevators were out, communication room-to-room was out, and even cellphones. So we reverted to the communications board in the lobby, and we were able to muster.

Officials grow increasingly concerned about the region’s most vulnerable residents, including the approximately 2,500 hospitalized patients in New Orleans. New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin urges people to move to the Superdome. Lurie sets up a rapid policy response group at RAND to work with the state of Louisiana and the city of New Orleans to figure out their needs.

A lot of people who were uninsured and likely to have undiagnosed medical conditions. Dialysis was suchDr. Nicole Lurie, director of the public health preparedness program at RAND

a problem.

Lurie: We had a lot of questions about how coordinated a federal response might be. I understood pretty clearly from my previous work that the population on the Gulf Coast, and New Orleans in particular, was from a public health perspective a pretty needy population. A lot of people with a lot of chronic disease. People with lower levels of education in general than the American public. A lot of people who were uninsured and likely to have undiagnosed medical conditions . . . Dialysis was such a problem, because people who didn’t get dialysis on time ended up in emergency rooms and hospitals with some frequency. It’s bad for patients, but it’s also one of those things that causes additional unneeded surge in the health care system. So we focused a lot on trying to do something about it.

In one bright spot, federal employees are paid on time, because the National Finance Center completes its work before evacuating.

John White: One of the saving graces was that Friday night, we [had] finished running payroll for that [two-week] period. So we had two weeks really to kind of deploy, get established. Who knows what would have happened if we were in the middle of a payroll cycle?

Who knows what would have happened if we were in the middle of a payroll cycle?John White, deputy director of the National Finance Center

Around midnight, people force their way into the Ernest Morial Convention Center in New Orleans, which has housed about 1,000 people rescued from flooded neighborhoods but is not stocked with food, water and other necessities.

Tuesday, August 30

By the end of the day, 20,000 people find their way to the Convention Center. Water rises around the Superdome and widespread looting is reported; 1.1 million homes and buildings in Louisiana and Mississippi have lost power.

Brown: People are stranded in 8 to 12 feet of water in the Superdome. In the operations center, I have military planners at [the Defense Department] handling the logistics of how to get people out of the Superdome in 12 feet of water. Silence is their response. We’re not really sure. We can start requesting Black Hawk [helicopters], try to get amphibious trucks and equipment in. But it’s going to take a while. So my decision is “Whatever you can do, just start doing what you can to move.” DOD starts moving stuff in, but it realizes it has to clear bridges, clear roads, so it’s taking them a while to move in. That’s a surefire indicator you’ve got things even worse than expected.

Thousands of patients and medical workers are stranded in New Orleans hospitals — most without power.

McGarvey: We got orders to travel [to Baton Rouge]. By the time we got people packed and plans made, it was afternoon when we left Jackson. We didn’t have GPS. It’s not really all that far from Jackson to Baton Rouge, but people didn’t know the roads. Because of the high winds there was debris all over the road so we had to be very careful. So many of the signs were damaged to the point where we couldn’t even find out what roads we were on. It was a good thing that one of the last things I packed was a Rand McNally road atlas. The power was out everywhere so we had to be very careful about gasoline consumption. Instead of a three- or four-hour trip, it took us nearly eight hours.

The most important thing that had to be done that night was setting up the pharmacy. Many of these people who wereCapt. Charles L. McGarvey, leader of the first U.S. Public Health Service team dispatched to the region

being transported were the

frail elderly.

McGarvey’s team arrives in Baton Rouge around 9 p.m., at the Pete Maravich Assembly Center, a 13,215-seat arena, where they are to establish a field hospital. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has shipped containers of medical equipment and supplies, and someone has sent three buses, with sleeping berths, to house team members.

McGarvey: We walked into the PMAC center and the floor was basically empty, with the exception of some people they had begun to transport up from New Orleans. Some were on cots, some were on the floor. Immediately our physicians and nurses began to triage those patients — there were just a few. I immediately had our group begin to set up all the cots on the floors. The most important thing that had to be done that night was setting up the pharmacy. Many of these people who were being transported were the frail elderly. They’d either lost their medications or were transported so quickly they couldn’t retrieve their medications. [The pharmacists] worked straight through the night to inventory and secure the drugs. By the next morning, when people were coming in ambulances and helicopters and buses and everything else, we had a full working pharmacy.

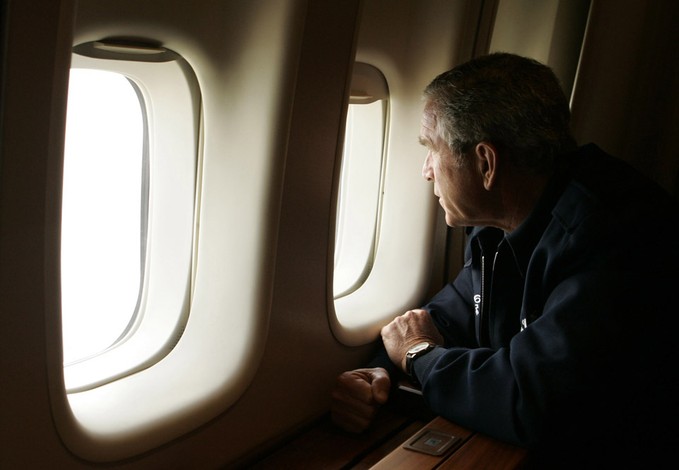

By Wednesday, 78,000 people are living in shelters, with 26,000 sheltering in the Superdome; those shut out seek refuge in the Convention Center. Blanco announces plans to evacuate people to the Astrodome in Houston. Air Force One flies low over the Gulf Coast so Bush can see the damage, and the president delivers his first speech on Katrina in the late afternoon. Health and Human Services Secretary Michael Leavitt declares a public health emergency. Mayor Ray Nagin declares martial law in New Orleans.

I said, “Gee, I wonder what’s wrong with the chemistry down there, what’s going on, why we can’t get our arms wrapped around this thing.Vice Adm. Thad Allen, chief of staff of the U.S. Coast Guard

By Thursday, evacuees start to arrive at the Houston Astrodome. Thousands remain in the Convention Center without supplies, and thousands more are stranded on highway overpasses in the city.

McGarvey: There were two other emergency response disaster teams that came in [later]. One was from New Mexico and one was from Indiana. They brought with them some excellent logistical people that helped us. They were able to set up a much better organization of the floor. Our people, along with [Louisiana State University] staff, provided most of the medical assistance in the way of triage and care. Obviously, we didn’t have ongoing food or water that we brought with us. The community was very good — the churches and the Red Cross. They set up kitchens and water.

Friday, September 2

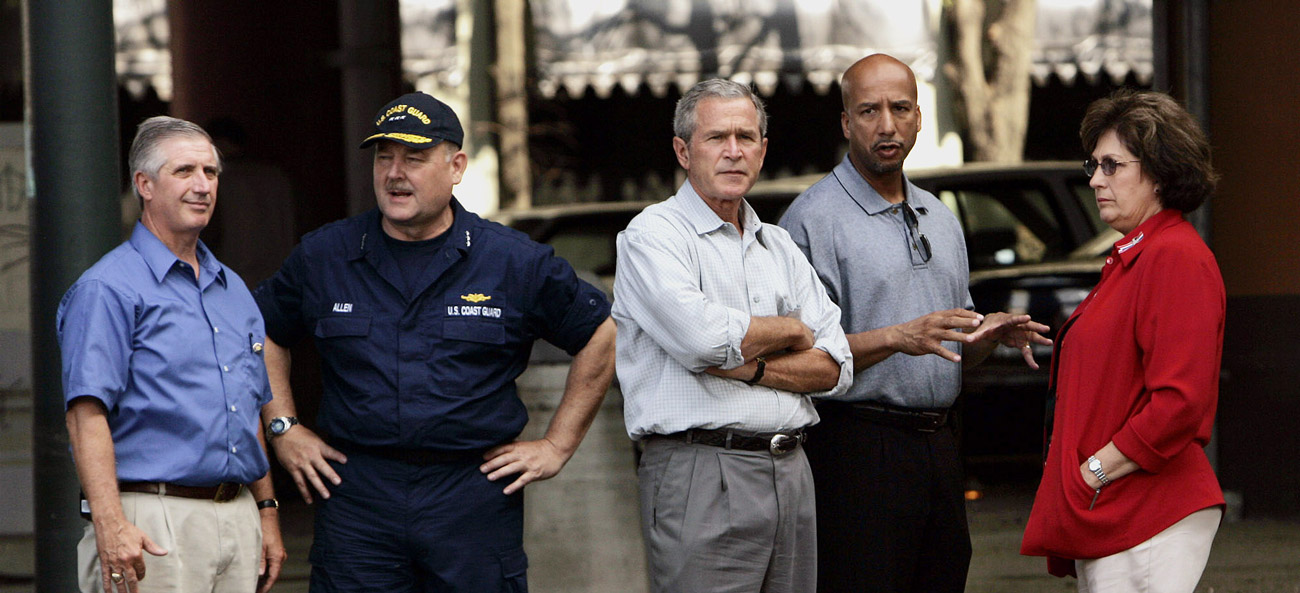

President Bush meets with Brown in Mobile, Alabama, at the beginning of a tour of the Gulf Coast. In a comment that becomes a caricature of the administration’s response, the president says: “Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job.”

Brown: The media is putting it all together, that we’re all out of touch, this administration doesn’t have a clue what it’s doing . . . Things were taken out of context [including jokes with staff]. I had the most loyal, civil staff. They know I cared about them. I supported them in whatever they did. If they made a mistake, [I had] that ability to take someone who has been sleeping in a car for three or four days, because there were no hotel rooms, and be able to joke with them. For the media to take that out of context shows how damned ignorant they are. It’s about how to manage people in a crisis, to give them their humanity back.

Thad Allen: I, like other [Coast Guard] flag officers, said, “Gee, I wonder what’s wrong with the chemistry down there, what’s going on, why we can’t get our arms wrapped around this thing.”

National Guard troops take control of the Convention Center and deliver 200,000 meals. Congress passes emergency relief funding. Hospitals in New Orleans are evacuated by late in the afternoon.

What Worked

Vice Adm. Thad Allen is in Chincoteague, Virginia, at a bed and breakfast with his wife for Labor Day weekend when Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff calls and asks him to go to New Orleans as deputy to Brown.

Allen: Obviously, that entailed a discussion with my wife and some pretty honest discussion about whether or not so many things had happened down there where windows had closed and the opportunity to do anything had passed. But in the end we kind of felt it was my duty to help, if there was a way I could. So I talked to Secretary Chertoff again and told him I’d be happy to go down there.

Allen returns home, recalls his Coast Guard staff to hand off responsibilities and takes a flight to Baton Rouge on Monday, Sept. 5. Brown is unavailable that evening, so Allen gets acquainted with the staff and is briefed on what’s going on.

Tuesday, September 6

Allen meets with Brown in the morning. Thousands of refugees from the Gulf Coast are en route to cities across the country.

Arriving on the morning ofVice Adm. Thad Allen, chief of staff of the U.S. Coast Guard

the 6th, which was over a week later, the city was still full of water: it was black, it smelled awful, there was no potable water, no sewage and

no electricity.

Allen: It was clear that [Brown] was pretty stressed out. We still hadn’t repaired the levees and the floodwalls that had collapsed and caused the city to flood. Until those breaches were repaired it was impossible to pump out the city. So arriving on the morning of the 6th, which was over a week later, the city was still full of water: it was black, it smelled awful, there was no potable water, no sewage and no electricity.

As the week goes on, hundreds of refugees arrive in the nation’s capital.

Lurie: I remember showing up at the D.C. Armory with a stethoscope around my neck and someone asking, “Are you a doctor?” I said yes, and they said, “Could you go see these patients?” That was the extent of my credentialing. We had a pretty significant influx of people who came into the Washington area. I had a very interesting set of experiences going there and providing medical care for people who had a variety of needs, watching our nonsystem at work.

The Bush administration has decided not to fully federalize the response in New Orleans and Mississippi, since there are state and local leaders on the ground with constitutional standing to lead the charge.

Allen: All of the resources being deployed down there throughout the week were basically self-deployed, reporting back to their own administrative chains of command. They were all doing very good work, and some of it was very heroic and we should be astounded that was put forward and what everybody was trying to do. But the fact of the matter was, it wasn’t an integrated response because the city lacked the capability to do that.

Allen moves communications equipment from Baton Rouge to New Orleans and unifies his response efforts with the Defense Department. He divides the city into sectors and assigns teams to handle each one. Local authorities lead search and rescue missions, with Allen’s team directing operations and providing support. Teams try to reach every house and draw symbols on them to indicate the living and the dead. On Sept. 9, Allen is named principal federal official for coordinating relief efforts. Michael Brown resigns on Sept. 12.

Allen: There were still people out there that still had to be rescued and at that point there were still people that had refused to leave that were then willing to come out after being in there for seven, eight days in those terrible conditions. We also had to start dealing with the very difficult situation of remains recovery. We got into a rhythm when we were having our meeting, we were planning how we were deploying our forces and at that point the response started to turn around. It stabilized. By the middle of that week you didn’t hear a lot after that about problems with the response.

It was our first real test of how we would respond to a domestic health crisis in an emergency, and I think the Public Health Service did a pretty good job.Capt. Charles L. McGarvey, leader of the first U.S. Public Health Service team dispatched to the region

McGarvey: It was the very first time, in the history of the Public Health Service, that it was ever involved in setting up a field hospital of that magnitude and function. It was our first real test of how we would respond to a domestic health crisis in an emergency, and I think the Public Health Service did a pretty good job in that situation.

Lew Drass: It took us a while to find [all the letter carriers]. A couple weeks. That was the first step — locating everybody. One by one, they made contact through the Postal Service and let you know where they were. We got the message out through the Postal Service to go to the post office [wherever you are] and go to work. So we’d find out that Joe Blow was working in Houston. Or somebody’s in Austin or somebody’s in Dallas. The mail was much like the people — the people ended up somewhere. The mail was like that too. Postal operations got up pretty quick. We had mail moving before the electricity was moving. It’s the dedication of the workforce. Rain, sleet, snow, dead of night, we still do our rounds. That slogan was never more true than in Katrina.

Fallout and Recovery

On Sept. 23, HUD Secretary Alphonso Jackson and Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff announce the Katrina Disaster Housing Assistance Program to help displaced families who would not normally be eligible for FEMA assistance.

Brian Montgomery: We set up this central command center with phones and workstations for people. That was something we set up within the Office of Housing, but we pulled in other folks in other offices within HUD. It was in headquarters here in Washington. That recovery center became the source of a lot of inbound calls for folks who were moving into these [vacant FHA-controlled] homes, [saying things like]: “Well, we can’t get the garage door open.” It wasn’t supposed to be for that, but God love ’em, if that’s your family and you can’t get into your garage, it’s a problem. We were becoming an apartment manager’s office. We worked that out at some point, so people knew who to contact. It was just another level of complexity that we hadn’t envisioned — in a good way, though.

One thing Katrina did do was pull back the curtain on what FEMA is, and what they aren’t. FEMA isn’t this 100,000-person agency, with tens of billions of dollars waiting in the safe toBrian Montgomery, assistant secretary for housing, Federal Housing Administration commissioner at HUD

be spent.

Saturday, September 24

Hurricane Rita makes landfall in Louisiana, west of New Orleans.

In early October, the Katrina Disaster Housing Assistance Program becomes operational. When the situation transitions from immediate recovery to dealing with the long-term fallout of the storm, Allen decides it is time to step aside as the primary federal official coordinating the response to Katrina in New Orleans. He stays on to deal with certain housing issues, but he says the sheltering process to this day needs clarity.

Allen: I think there ought to be a clear cutoff regarding sheltering and moving to long-term sheltering options between FEMA and HUD. There would be a positive handoff, and HUD ought to take the responsibility at that point as FEMA needs to go back, and say, “We’re gonna get ready for the next storm.” They tried to do that during Katrina, they tried to do it after Sandy; in my view that still remains a transition point that is not clearly laid down in authorities and jurisdiction within HUD or the other agencies.

Montgomery: One thing Katrina did do was pull back the curtain on what FEMA is, and what they aren’t. FEMA isn’t this 100,000-person agency, with tens of billions of dollars waiting in the safe to be spent. They really are a smaller agency that relies a lot on contractors. Just the sheer magnitude of the number of people obviously created problems, and by the way, more hurricanes were coming to the Gulf Coast and southeast Texas [Rita and Wilma].

We’re political appointees, but the people who are the boots on the ground at FEMA, they don’t give a rat’s ass about what somebody’s politics are, or their skin color, or theirMichael Brown, director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency

bank account.

FEMA had done a marvelous job with those three or four hurricanes that had crisscrossed Florida in ’04. I’m not really interested in rehashing where breakdowns occurred. I think that people learned going forward that there needs to be a much more collaborative approach between city government, state and federal.

Allen: Now, there was criticism leveled at me, some of it internal at FEMA that this really exceeds the authorities of somebody who’s down there just to provide resources and assistance to local governments. And I can understand where somebody who’s looking at it [might think that]. You have this large command-and-control machine that’s driving these decisions. But I can tell you every day we made a plan for the next day, and if there was significant objection by the city, we altered the plan.

Brown: It always just infuriated me when people would accuse me and Bush, that we were either playing politics, [or] that we didn’t like black people, we didn’t like poor people, and we only cared about white Republican districts. I found it despicable. It’s also a slam on the people who actually do the work. We’re political appointees, but the people who are the boots on the ground at FEMA, they don’t give a rat’s ass about what somebody’s politics are, or their skin color, or their bank account. I watched urban search and rescue teams, and our community relations team staff who were pulling people out of buildings, who were incredibly dedicated. They just wanted to do the right thing for the people we serve.

Montgomery: Having been at the White House during Sept. 11, the mentality we had back then was “Let’s fix it, let’s get help” — it definitely helped us later on dealing with Katrina. I learned the value of “Let’s sit down with the career staff who have been here, some of them for decades.” [In one meeting] one hand went up, and this man said, “You know, we do have this [Memorandum of Understanding] with FEMA as a holdover from the hurricanes that hit Florida in 2004, whereby we can house families, or seniors, in vacant FHA homes, and that FEMA would essentially pick up the cost.” And I said, “Where is that MOU?” So, we got all over that MOU fast. Not every HUD vacant home at the time was in move-in condition, so we immediately [brought in] contractors who managed HUD’s real estate-owned portfolio, and said, “We need to get these homes ready for occupancy.” I think we eventually housed about 3,000 families in vacant FHA homes, scattered all over.

After Katrina, some idiotic senator wanted to know whether, 'If we’re doing this Pam exercise, why weren’t we doing changes to deal with that?' . . . I thought, 'You’ve been in that Senate x-number of years, you know how it long takes to move the ship of state one degree.'Michael Brown, director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency

Katrina has wiped out two large public housing developments in East Biloxi, Mississippi, and displaced about 500 families living in public or subsidized housing in Biloxi. (The number of families the housing authority serves has tripled since Katrina — from about 600 families before the storm to 1,800 families today.)

Bobby Hensley: We went from being a housing manager before the storm, to being a construction company almost, primarily, after the storm. Now I’m slowly, slowly bringing my people back to being housing managers, primarily. We have helped with day care, we have adult day care now, we have an assisted living facility now, we have a free clinic that we help sponsor. We have gotten involved with helping people in ways that I would never have seen before, and it’s become a necessity now for a lot of these people, [to] maintain some kind of normal life.

On Oct. 11, the Army Corps of Engineers removes all the floodwaters from New Orleans—43 days after Katrina’s landfall.

Riley: The Corps really took a beating. There were 20 hearings on Capitol Hill [among other investigations, including one Riley commissioned]. Typical of any disaster, whether it’s an airplane or 9/11, you’ll find not one contributing factor but usually a minimum of 100 contributing factors. People may have thought these were good decisions at the time, but they turned out not so good. All had a role — state, federal, private. Some people had swimming pools right up to the levees, for example, or trees on a levee, which is dangerous.

Brown: I’ll never forget that after Katrina, some idiotic senator wanted to know whether, “If we’re doing this Pam exercise, why weren’t we doing changes to deal with that?” Looking at her, I thought, “You’ve been in that Senate x-number of years, you know how it long takes to move the ship of state one degree, and you’re criticizing me for having not made, in less than 90 days, regulatory and policy changes in the money and equipment FEMA might need for this kind of disaster? How stupid can you be? This showed this wasn’t a public policy discussion but a political discussion. People often forget — Katrina was both a public policy issue and political issue.

I personally called every single letter carrier that had been displaced to find out what their life was about. 'Do you want to go back? Do you want toLew Drass, business agent for the National Association of Letter Carriers

go home?'

Winter 2005-2006

Employees of the National Finance Center move back into their headquarters in New Orleans East. Nearly 1,000 employees are deployed to Philadelphia; Grand Prairie, Texas; and Smyrna, Georgia, for a few months after the storm while White and the rest of the senior leadership team set up a command center in Alexandria, Louisiana — about three hours northwest of New Orleans.

White: We now have one [continuity of operations plan] site, which is in Shreveport [Louisiana], so all the people can go to one place. That was a big issue because you had people who worked side by side, and then they had to separate. [Also], we’ve got the primary computing facility that we set up in Denver. [Prior to Katrina, the primary computing facility was in New Orleans].

Drass: I personally called every single letter carrier that had been displaced to find out what their life was about. “Do you want to go back? Do you want to go home?”

Every postal employee who fled New Orleans is given the opportunity to go back if they want to, even years later.

Drass: I have a file cabinet drawer that I’ve kept all these years. It has all the people who left, where they went, when they went back, and all the little deals that took place. I would have people call and say, ‘I’m in Chattanooga, Tennessee.’ I would talk to the Postal Service and give them a transfer. I was like the travel agency for the letter carriers. That was good work.

White: We lost a lot of employees [who left the organization]. We lost about 10 percent [of 960 employees in the New Orleans facility].

You look back on that, you can’t make people leave sometimes. But they won’t get a chance to stay the next time, if I’m here.Bobby Hensley, executive director of the Biloxi Housing Authority in Mississippi

December 2006

Congress passes the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, which establishes within the Health and Human Services Department a new assistant secretary for preparedness and response. President Obama nominates Dr. Nicole Lurie to the position in May 2009.

Lurie: Our goal is to protect people in communities and plan for disasters. Part of what you do is look at the kinds of people and populations that are likely to get in trouble and think proactively about what you can do to increase their resilience, what you can do to increase the resilience of those communities, and what you can do to make it so those bad things are less likely to happen.

February 12, 2012

The last FEMA trailer leaves New Orleans — more than six years after Katrina.

Montgomery: The general public naturally thinks of housing and “We need food, we need clothing.” What they don’t necessarily think about, unless they’re impacted by it, is how [the disaster] impacts the schools and the Department of Education, and what they can do; the Department of Labor with workforce grants; USDA with assistance to farmers whose crops were destroyed; the Department of Energy and price gouging. It’s amazing, and I did some of this when I was running Cabinet affairs at the White House. It’s amazing how deep it gets, and how long it goes. It goes on and is equally as important as the shelter and housing.

July 2015

HHS releases the digital emPOWER Map, which is updated monthly to provide ZIP code-level data on all Medicare patients who rely on electricity-dependent equipment, such as ventilators or oxygen.

Lurie: Now in advance of any coming storm we can give [local officials] the names and addresses of people they need to get out of harm’s way, or get into early dialysis. We know how many people, what languages they speak, and we know what their burden is with chronic disease. So we know not only who’s on dialysis, but we know that 40 percent of the population is diabetic, or overweight enough that it’s going to be hard to evacuate them, or whatever. That’s a huge advance, just taking advantage of all the information that’s out there and putting it together in an actionable way.

There’s been a pretty significant decrease in funding for emergency preparedness. I think there was kind of this notion that we could just buy a lot of stuff and put people through training and we’dDr. Nicole Lurie, director of the public health preparedness program at RAND

be done.

Hensley: We certainly made our share of mistakes. We were in the middle of that [housing redevelopment] project, we could have been better prepared. I never imagined a Katrina, let me just say that. I have never in my life seen devastation like that, so it never crossed my mind that I could be completely wiped out in the area, like we were. I thought we were very well-insured, and we weren’t, for what happened. We lost several lives in some of our properties. I could have done a better job of forcing people out before the storm. You know, you look back on that, you can’t make people leave sometimes. But they won’t get a chance to stay the next time, if I’m here.

Lurie: Some remaining issues and gaps I see are, No. 1, people’s memories are short. There’s been a pretty significant decrease in funding for emergency preparedness. I think there was kind of this notion that we could just buy a lot of stuff and put people through training and we’d be done. But people in the workforce turn over all the time. People need to train and practice and exercise in health care facilities and communities all over the country every single year.

McGarvey: You have to be flexible in an ever-changing environment, and you have to plan ahead and expect the worst.

Where They Are Now

Max Mayfield is a hurricane specialist with WPLG Local 10, the ABC TV news affiliate in Miami.

Maj. Gen. Don Riley, who retired from the Army in 2010, is a senior vice president at Dawson and Associates, an advisory and technical services firm on federal water resources issues and environmental regulatory policy in Washington.

John White is director of the National Finance Center.

Thad Allen became the 23rd commandant of the Coast Guard, retiring from the service in 2010. He now is a senior vice president at Booz Allen Hamilton.

Michael Brown resigned from the Homeland Security Department in 2005 amid heavy criticism. He’s now a consultant and corporate speaker and hosts a syndicated talk radio show for KHOW in Denver.

Dr. Nicole Lurie is the assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Health and Human Services Department, a position created by Congress following Katrina.

Lew Drass was elected national vice president of the National Association of Letter Carriers in 2014.

Bobby Hensley remains the executive director of the Biloxi Housing Authority in Mississippi.

Brian Montgomery is vice chairman of The Collingwood Group, an advisory services and business development firm in Washington.

Capt. Charles L. McGarvey is retired and works as a consultant in Rockville, Maryland.

This was a collaborative project by the staff of Government Executive. Interviews were conducted by Kellie Lunney (Hensley, Montgomery, White and Mayfield); Charles S. Clark (Brown and Riley); Eric Katz (Allen and Drass); and Katherine McIntire Peters (Lurie and McGarvey). Lunney, Peters and Amelia Gruber wrote the narrative. Ross Gianfortune conducted photo research and contributed to design. Chawndese Hylton provided research support. Tom Shoop and Susan Fourney edited the piece. Katie Strylowski designed the piece.