Ask Donald Trump why he should be president, and he will likely tell you that he built a “tremendous” business that prepared him to step in as the nation’s CEO.

In fact, Trump last year told Breitbart that managing “the country may be easier than building a business.”

The boisterous and controversial Republican nominee is seeking, for the first time in his life, to make the transition to the public sector with a solemn vow to purge the federal government of the “stupid people” who run it. No more bad deals, no more weak leadership and no more inadequate management, Trump has promised.

He has offered few details on exactly how he would accomplish this good-government revolution, aside from vague references to hiring “the best people,” eliminating waste and transforming the missions of a few agencies. But a review of Trump’s business record and his own writings, along with interviews with his former employees, journalists who have covered him and academics who have studied his foray into politics, helps to paint a picture of how the man seeking the country’s highest office would run the bureaucracy.

Some of those who know Trump best, including journalist David Cay Johnston, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of the just-released The Making of Donald Trump, say analyzing his management tactics and skills is a fool’s errand.

“You cannot think of Donald Trump in terms of policies and in terms of management strategy, because there’s nothing there,” said Johnston, who has covered Trump for decades. “It’s all bluster.”

Timothy O’Brien, author of TrumpNation: The Art of Being the Donald, said Trump’s modus operandi does not point to a coherent set of guiding principles.

The real estate magnate has led Trump Organization — which boasts 20,000 workers and has served as the launching pad for every one of his ventures into the public consciousness — “very by the seat of his pants,” O’Brien said, “without a lot of rhyme or reason.”

Still, while Trump has often surrounded himself in a cloud of uncertainty, his story is woven with some common threads that would likely follow him into the Oval Office: a heavy reliance on a small group of loyal advisers, an aversion to micromanagement and little patience for getting deep in the weeds of policy issues.

Donald Trump speaks during the final day of the Republican National Convention in Cleveland on July 21. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Hands-Off Leadership

Donald Trump is one of the most famous people on Earth, but he maintains that few truly know him.

“People who work for me know there’s a lot more to me than my public persona,” Trump wrote in his 2004 memoir Trump: How to Get Rich. Those close to the candidate have indeed described throughout the campaign two Donalds — the extrovert who speaks his mind and confronts his adversaries, and the more deliberative man behind the scenes who listens, reflects and plans.

Trump has kept a tight-knit set of advisers and decision-makers by his side throughout his career, with his children serving as his most-trusted confidantes. Mike D’Antonio, author of another recent Trump biography, Never Enough: Donald Trump and the Pursuit of Success, said the candidate has consistently maintained a “small inner circle.” D’Antonio noted that when he has visited the Trump Organization offices on the 26th floor of Trump Tower in Manhattan, he has seen “very few people.”

Trump’s top subordinates, in addition to his family members, “tend to be people who have stayed with him for a very long time,” D’Antonio said.

When it comes to rank-and-file workers, Trump tends to maintain a distance and typically shies away from the day-to-day operations of his projects. “He usually leaves the nitty-gritty of everything to others,” O’Brien said.

Randal Pinkett, a former champion of the Trump-hosted reality television show The Apprentice who served as an executive for Trump Organization’s Atlantic City, New Jersey, casinos, said Trump led by delegating.

“He was not involved in a hands-on way,” Pinkett explained. “It was a combination of Donald setting expectations and at the same time empowering the executive team to lead the business to a place where it was more profitable, reducing costs and growing revenue.”

Ultimately, Trump created an echo chamber in which “people within Donald’s inner circle tend not to challenge him,” Pinkett said. “I find that he’s often surrounded by people who think like him and reinforce his way of thinking.”

While Pinkett said Trump has little interaction with those outside of his inner circle, the candidate has preached a different approach. In a section of How to Get Rich called “Donald J. Trump School of Business and Management,” Trump’s prescription for a good leader included: “Make yourself accessible to your employees.”

Trump advised: “If they feel they can bring ideas to you, they will. If they feel they can’t, they won’t. You might miss out on a lot of good ideas, and pretty soon you might be missing a lot of employees.”

But the Republican nominee also described his relationship with his employees as Machiavellian, reminiscing about tricks he has played on his workers to covertly determine their productivity. He told D’Antonio, “it’s a good idea to be a little bit paranoid.”

Donald Trump, seeking contestants for “The Apprentice” television show, is interviewed at Universal Studios Hollywood on July 9, 2004, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Ric Francis)

Because Trump generally concerns himself only with top-level operations, the vast majority of the career civil service would likely not face his unpredictable methods. In Atlantic City, Trump “certainly didn’t get involved with the needs, careers, aspirations and problems of employees at the grassroots level,” O’Brien said.

While Trump’s business success has formed the foundation of his candidacy for president, he has certainly experienced failure. From his ill-fated airline venture to his steak sales and his mortgage enterprise, Trump has suffered high-profile duds. The businessman has not fared much better in some evaluations of his management style.

In 1999, Fortune surveyed 10,000 executives and analysts to rate an array of publicly traded companies on their management; Trump Hotels and Casinos came in dead last of the 496 organizations analyzed. The company was among the basement dwellers in categories such as quality of management, employee talent, keeping talent and financial soundness.

D’Antonio suggested those findings are not particularly surprising, saying Trump specializes in deal-making, not management. The federal government, D’Antonio said, “requires very effective operating experience . . . and that’s not his strong point.”

O’Brien forecast those problems would only be exacerbated if Trump is called upon to run the complex and cumbersome bureaucracy. “He’s never come close to anything in his work experience that approximates managing an organization with 2 million employees,” O’Brien said, referring to the size of the civilian federal workforce.

Government 101

Many observers of Trump and the federal sector warn that the candidate’s apparent lack of understanding about how the government functions could be a problem. Lara Brown, interim director of The George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management, said an attendee of a summer meeting on Capitol Hill between Trump and congressional Republicans told her Trump was unaware that Article I of the Constitution refers to the powers of the legislative branch.

Brown said Trump, if elected, “would be shocked with the amount of power presidents don’t have.” She predicted his chief of staff, the White House counsel and the attorney general would “spend a lot of time educating him on systems and processes,” impeding his ability to accomplish anything in his critical first 100 days.

Trump’s dismissive assessment of complex national challenges and lack of patience for details could make his learning curve even steeper. The political neophyte told The Washington Post earlier this year that reading long briefing documents was a waste of his time because he could grasp “the gist of an issue” with little material.

“I want it short,” he told the Post. “There’s no reason to do hundreds of pages because I know exactly what it is.” On foreign policy, for example, Trump said on MSNBC’s Morning Joe in March that he trusts his own gut.

“I’m speaking with myself, No. 1, because I have a very good brain and I’ve said a lot of things,” Trump responded, when asked about his consultants.

Brown, who has written multiple books on presidential leadership, said candidates who go on to become good presidents are “deeply curious” and “highly perceptive.” Individuals fail, she added, when they become victims of their hubris. “They start to believe their own spin.”

As a candidate, Trump has shown a tendency to propose or back policies that would undermine laws designed to protect the civil service system.

At a June rally, a supporter asked Trump why the government did not replace all Transportation Security Administration employees with military veterans, suggesting the agency “get rid of all these hibijabis” (apparently referring to the hijab coverings worn by many Muslim women).

Trump’s response: “I understand. And we are looking at that. We’re looking at a lot of things.”

Veterans already receive hiring preference in the federal government, but manipulating the process so only one class of applicant could get the job for the purpose of blocking out a religion would violate just about every civil service and equal opportunity law on the books.

“He does not understand the duties and responsibilities of the president, and how the Constitution works,” said Johnston, the Trump biographer and current professor of federal regulatory law at Syracuse University.

GW’s Brown echoed that assessment. “I just imagine that he would run afoul of . . . rules and procedures that are actually there to protect and serve the public safety,” she said.

This tendency could also lead Trump to push employees to carry out illegal tasks, critics warn. Trump is a litigator by nature, Johnston said, and would likely find lawyers who would “run roughshod over the law” by drafting memoranda that give Trump cover to do whatever he wants. “There will be real trouble for executives at federal agencies,” Johnston added.

One area in which Trump has demonstrated his affinity for litigation is through his company’s use of contractors; a USA Today report found the GOP candidate has been involved in 60 lawsuits involving employees and vendors alleging he never paid them, while an additional 253 subcontractors said they were not paid in full or on time while working on Trump’s Taj Mahal Casino in Atlantic City.

Donald Trump marks the opening of the Trump Taj Mahal Casino Resort in Atlantic City, N.J., on April 5, 1990. (AP Photo/Mike Derer, File)

Johnston said he has spoken with additional business owners who declined to take their issues to court because their legal fees would have exceeded the amount Trump allegedly shorted them.

Given this pattern, it’s not out of the question that the businessman might attempt to bend government contracting rules in pursuit of his objectives. “A well-documented business record of stiffing vendors . . . would suggest he’d bring a lot of laissez-faire attitude about responsible contractual relationships to the federal government,” O’Brien said.

New Jersey Republican Gov. Chris Christie, who is chairing Trump’s transition team, recently told donors that a Trump administration would purge the federal government of employees loyal to President Obama — something that would require rewriting civil service laws designed to prevent political patronage. Good government experts note that independent agencies already provide oversight of political appointees “burrowing in” to career positions during presidential transitions, and revising the law to root out career civil servants who might have a particular affinity for Obama would essentially return government employment to a spoils system.

The two words Trump is perhaps most associated with are “you’re fired,” and Christie has reiterated that “Donald likes to fire people.” Trump, however, has argued the catchphrase is just another area in which his public persona and his private demeanor part ways.

“The truth is,” Trump wrote in his management guidelines, “although I’ve had to fire people from time to time, it’s not a big part of my job. I much prefer keeping loyal and hardworking people around for as long as they’d like to be here.”

Johnston did not argue with that self-assessment, but noted loyalty surpasses any other asset: “Donald has gotten rid of competent executives in the past in favor of people who would do whatever he asks for.”

A shovel with the Tump logo during a groundbreaking ceremony for the Trump International Hotel at the site of the Old Post Office in Washington on July 23, 2014. (AP Photo)

Big Government Conservative?

Trump has made broad promises to fix government. “I'm going to get great people that know what they're doing,” he said in 2015 on ABC’s This Week, “not a bunch of political hacks that have no idea what they're doing, appointed by President Obama.” But, unlike most Republican politicians, Trump has made no vow to shrink the overall federal footprint.

The nominee has promised to eradicate waste at federal agencies, saying in a GOP primary debate: “We will cut so much your head will spin.” In his Republican National Convention acceptance speech, he said he would ask every agency head to “provide a list of wasteful spending projects that we can eliminate in my first 100 days.” He has also said he would freeze regulations and eliminate the Education Department, although the latter promise perhaps conflicts with his claim that the three most important functions of government are security, health care and education.

Still, Trump has repeatedly rejected the traditional Republican commitment to smaller government in favor of big government programs. He said he would preserve Social Security, vastly increase military spending and at least double Democratic rival Hillary Clinton’s plan to spend $275 billion on infrastructure. He has said cuts to NASA have led the country’s space program to resemble that of a “third-world nation,” and forcefully defended government’s right to claim eminent domain on private property. He has opposed returning federal lands to individual states (saying federal ownership was the only way to “keep the lands great”) and supported increased federal agency spending to address the Zika virus outbreak.

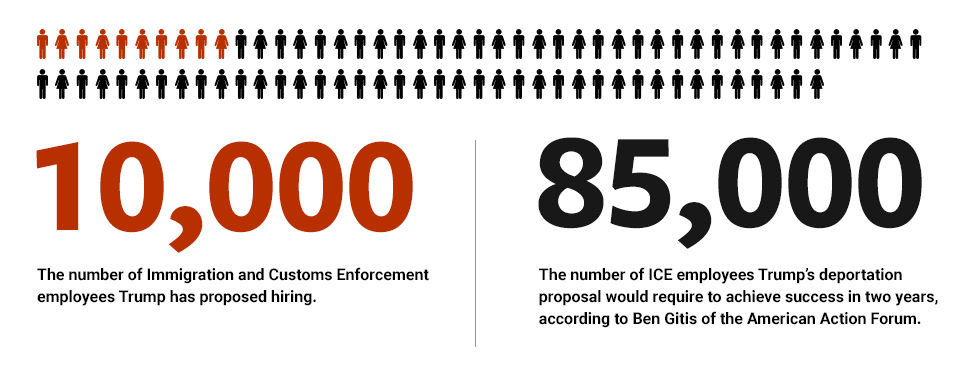

Two of his most discussed policies — building a wall along the southern U.S. border and deporting all undocumented immigrants — would likely require a massive increase in government spending and personnel.

Ben Gitis, director of labor market policy for the American Action Forum, said Trump’s deportation proposal would require 85,000 new Immigration and Customs Enforcement employees to accomplish the task in the Republican’s first two years in office. The impact would trickle down to all levels of the Homeland Security Department’s operations, from a tenfold increase in detention beds to chartering 17,000 flights, according to Gitis, who has released multiple papers studying the economic impact of Trump’s plans. Trump, however, has proposed hiring only 10,000 new ICE agents.

At the current staffing level, Gitis estimated, it would take 20 years to complete the deportation process and cost between $400 billion and $600 billion. Other logistical difficulties noted include achieving a twentyfold increase in government immigration attorneys or shortening the holding time for detained immigrants from 30 to three days. A shorter timeframe, Gitis said, would likely increase DHS’ error rate, leading to the expulsion of individuals legally in the country.

As for the border wall, a New York Times investigation this year found it would be logistically difficult to build, citing contractors who said Trump has vastly undersold the costs, academics who said it is impractical, and engineers and environmental scientists who said it would disrupt water exchanges between the United States and Mexico.

David Aguilar, the Border Patrol chief when the George W. Bush administration built 652 miles of fencing along the U.S.-Mexico border and now a principal at GSIS, called Trump’s wall “unrealistic” and “unnecessary.” Aguilar recalled the “heart-wrenching” tactics his agency had to deploy when claiming eminent domain over privately owned property.

Proposals like Trump’s wall are “taking front-and-center attention when there are so many other things that need to be addressed that are, frankly, so much more important,” Aguilar said.

In his 2015 book Crippled America: How to Make America Great Again, Trump attempted to address any concerns about building the wall with what has become another Trumpism. “Nobody can build a wall like me,” he wrote. “People will say you can’t do it: ‘How do you build a wall across the whole border?’ Believe me, it can be done.”

Brandon Judd, president of the National Border Patrol Council, which is the only federal employee group to endorse Trump, said his union’s members trust the Republican nominee to see the job through. Trump has reached out to the group to solicit feedback on his plan, including where the wall would be most effective and where it is unnecessary.

Ultimately, the group’s endorsement stemmed from Trump’s corporate experience and promises to give Border Patrol agents the resources necessary to carry out federal laws.

“Do we want the same old status quo,” Judd said, “or do we want someone who has run businesses and can run the business model for government?” He added that Trump has promised the union to hold agency management accountable by firing bad actors, a vow the Republican nominee has also made in reference to the Veterans Affairs Department.

Judd said Trump’s wall and his promise to end Obama administration policies that are encouraging immigrants to breach U.S. laws will help to better protect federal personnel at the border. “We have to put our agents in the safest position we can put them in,” said Judd, who has worked at the Border Patrol for 19 years. “And Donald Trump offers that.”

Reaching out to the union could show another side to Trump, one to which he alluded in How to Get Rich. “If people are your resource,” he wrote, “you’d better try to learn something useful about them. Being able to do so is what makes a good manager a great one.”

Donald Trump speaks to reporters after arriving for a visit to the Mexican border in Laredo, Texas, on July 23, 2015. (AP Photo/LM Otero)

Rough Seas

Trump acknowledges his leadership style can be choppy, but defends his chaotic structure as a management necessity (while perhaps forecasting what a Trump presidency would look like).

His office, he wrote in How to Get Rich, can resemble a “family fight in progress.” But, he said, “if you want smooth sailing, move to the Mediterranean.”

The transition to the White House would be difficult for Trump, said The George Washington University’s Brown, a former Education Department official, because in business — especially Trump’s — “all the power resides at the top.” In government, by contrast, “every single decision at the business level has to be made by all of the shareholders,” she said.

While Trump is promising to overhaul the way government operates, he is likely to run into a combative Congress, limits on his own authority and the glacial pace at which the federal bureaucracy moves.

“He thinks the president can just snap his fingers and make things happen,” Brown said, again noting the differences between the private and public sectors. If elected, she added, “He would be so stunned by the entire process.”

In perhaps his best-known book, The Art of the Deal, Trump said he is good at two things: “overcoming obstacles and motivating good people to do their best work.” He added: “One of the challenges ahead is how to use those skills as successfully in the service of others as I’ve done, up to now, on my own behalf.”

If things go his way in November, he will finally have the opportunity to do just that — if he is willing to learn how.