In April 2006, a young Democratic senator from Illinois and a graying fiscal conservative from Oklahoma introduced legislation to create a searchable database of federal monetary awards, essentially a Google for government spending. The site would empower citizens to monitor how their tax dollars are spent and uncover waste. President George W. Bush signed the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act five months later and USASpending.gov was born in 2007. While co-sponsor Sen. Tom Coburn, a Republican, pushed for greater financial transparency until retiring in December 2014, many say the other co-sponsor, now President Obama, ran out of steam.

USASpending could not account for $600 billion in grants and awards, when last checked by federal auditors. The White House Office of Management and Budget balked at a legislative proposal to establish a new watchdog agency that would ensure agencies deliver all spending data in searchable formats. Whether due to disorganization or fear of disgrace, agencies to this day have not released financial information on the Web in formats that machines and people can understand, observers say. At a time when the government is doling out $3.8 trillion annually, taxpayers are questioning where all that cash is going.

Obama once was—and maybe still is—one of them.

He ran for president with a message: “Every American has the right to know how the government spends their tax dollars, but for too long that information has been largely hidden from public view.”

Once elected, Obama’s administration stood up the Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board to keep tabs on $840 billion in economic stimulus money intended for shovel-ready projects. Board Chairman Earl Devaney and anti-pork Republicans saw to it that Recovery.gov did just that. It was discovered, for example, that a construction company superintendent covered up improperly installed bolts on a $21.6 million bridge-building effort. Kip Harris, the former manager, was sentenced to three years of probation and fined $750 along with a $100 special assessment.

When the board wound down in September, estimates pegged the amount of money recouped, forfeited or saved at $157 million.

There is a fear in this administration that anything that is embarrassing should be somehow classified.

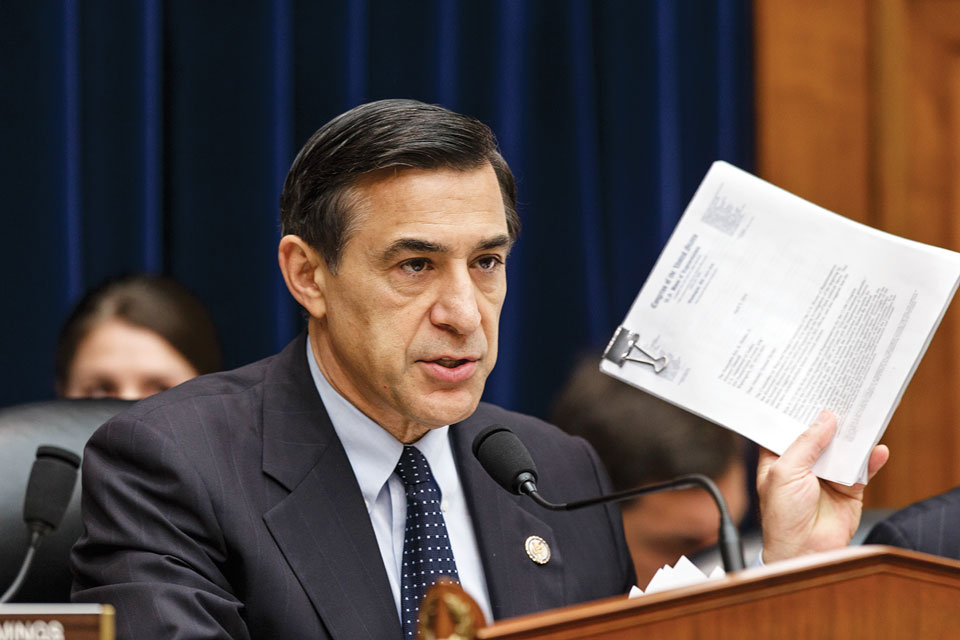

Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif.

“Bridges were falling down around America. We created a map of where those bridges were and then we overlaid that map with the money to see if the money was going to the bridges that most needed it or was going somewhere else,” Devaney recalls. “I think the bad guys looked at that money and saw how transparent it was and said, ‘let’s go steal Medicaid money because this isn’t worth it.’ ”

In December 2011, Devaney retired after recommending that Obama extend the money-tracking technique to all government awards. “Here’s where things come to a screeching halt,” he says. “I’m sad to say, I don’t see much progress since the day I left.”

There is one exception. In 2014, Obama signed a bipartisan measure mandating agencies use consistent data standards for spending, along the lines of what Devaney had advised. The Digital Accountability and Transparency Act was ushered through by Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., and Sen. Mark Warner,

D-Va. The DATA Act, introduced in 2011, “ended up being watered down considerably,” Devaney says. “The administration opposed just about everything that was in the original act.”

The first proposal would have carved out a new agency like the Recovery Board to log all federal expenditures. Administration officials argued OMB already has an office that serves that purpose. Then the White House reportedly wanted to remove the key component of the bill—a uniform way for agencies and contractors to report disbursements so that USASpending’s data would be accurate and searchable. Ultimately, the administration came around, after lawmakers extended deadlines for standardizing reporting and assigned OMB more decision-making responsibilities.

Issa, then chairman of the Oversight and Government Reform Committee, commended the Recovery Board for illustrating cash flows for the public, even when the pictures made the board look foolish. At one point the website depicted more congressional districts than existed in some states, he says. The staff “took the incredible criticisms of bad data,” Issa says, noting their premise was “put out the data, take the embarrassment, make the fixes, the data gets better.”

There is no active equivalent to that window into government spending right now. Unlike Recovery.gov, USASpending.gov data comes from agency reports that do not categorize expenditures in a consistent manner, so it’s impossible to analyze.

The Case for Transparency

Issa contends that with better data, the scandal that erupted in 2012 over hundreds of General Services Administration employees partying in Las Vegas might have been averted. A 2010 photograph of a GSA senior executive bathing with drinks close at hand incensed lawmakers on Capitol Hill.

“People think that the man in the bathtub with two wine glasses was the embarrassment. The real embarrassment was he didn’t have a fund to do what he did,” Issa says. “If you had an open data process, just the fact that simultaneously multiple funds were being spent all in Las Vegas from GSA would tip anyone off that you shouldn’t be having five different unrelated events occurring” in the town.

Obama did not endorse these events, Issa acknowledges. However, a culture of secrecy flows from the top down, he says. “There is a fear in this administration that anything that is embarrassing should be somehow classified,” he says.

The hiding of undeniably public information has eroded public trust, Issa asserts. Edward Snowden, the ex-intelligence contractor who leaked surveillance secrets “is a good example of exactly why the DATA Act and transparency is needed. Snowden’s defense is the government should have disclosed this, the government was doing wrong,” Issa explains. “The more information that is in machine-searchable, metadata-rich, personally identifiable, extractable from any report or field—the less apparent secrecy there is.”

If you are concerned about the accountability of government to the people, then you must start with spending.

hudson hollister, data transparency coalition

Issa points out the distinction between illuminating public data and exposing restricted data. “I think we have to realize that I don’t want to know the secret codes for our nuclear weapons and I don’t want the public knowing it,” he says. “What’s important is that open data standards properly implemented and then appropriately released can give the American people both the confidence in their government’s activities and save hundreds of millions of dollars in waste.”

Devaney, too, says the administration’s attitude toward financial disclosure is not helping its public image. The information is “secret only to people that don’t want other people to see it. It’s not because it could lead to disaster for the nation,” he says. “You can’t have transparency without embarrassment.”

Obama seemed open to that risk in the early years of his administration.

At the start of his first term in 2009, the White House website posted an oath pledging to institute “an unprecedented level of openness in government.” About a year later, Obama followed up with a directive instructing agencies to publish meaningful data sets and act under a presumption of openness.

Citizen Watchdogs

Some former White House officials, who were there at the time, say transparency into government functions is clearly visible on the Web.

For instance, the Commerce Department’s stimulus-funded National Broadband Map, which charts the country’s high-speed Internet infrastructure, helps physicians serving low-income areas avoid certain financial penalties. Doctors in designated rural areas who fail to make “meaningful use” of electronic health records are exempt from Medicare payment cuts because Internet connectivity is limited.

“The opening-up of data from one government agency is being repurposed and reused now to help advance the mission objectives of a second government agency,” says Aneesh Chopra, who was the first U.S. chief technology officer from 2009 until 2012.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau also sprinkles sunshine on government records to save money. The bureau stripped the names off complaints received about products and services, publicized the contents online, and encouraged citizens to parse them for trends. “Maybe the agency lacks the tools or the people, but by opening up the underlying data, millions of Americans can help them find patterns of financial deception, or whatever the term of art might be, to help make sure that we have a high-functioning consumer-protected financial products marketplace,” Chopra says.

After he left the administration, the White House in May 2012 unveiled a digital government strategy centered on releasing data in smartphone-friendly formats. One year later, before enactment of the DATA Act, the administration issued an open data policy requiring agencies to collect and disseminate information in machine-readable formats.

Critics, however, say the White House has not prioritized the release of the most important information.

Former U.S. chief technology officer Aneesh Chopra says opening up data has helped missions across agency lines.

“It’s not enough to be committed to transparency or to open data generally—if you are concerned about the accountability of government to the people, then you must start with spending,” says Hudson Hollister, executive director of the Data Transparency Coalition, who helped write the DATA Act when he was counsel to the Oversight and Government Reform Committee. “The efforts that the Recovery Board made and the proposal in Congress to [expand that approach] to all spending encountered opposition from the White House.”

The law requires agencies to begin reporting their spending using new data standards by May 2017. In addition, the White House must run trial programs to test whether the formats will allow contract and grant recipients to report expenditures.

U.S. Comptroller General Gene Dodaro, head of the Government Accountability Office, told the Senate Commerce Committee on Oct. 1 that White House officials are in danger of falling out of compliance with the law. “I am concerned that they haven’t really identified the proper pilot for the contract side—and they haven’t finalized plans yet for the grant side,” he told lawmakers. “If they don’t start soon, this summer, they’re not going to be able to meet that requirement.”

What Does ‘Open Government’ Mean?

Obama administration officials declined to comment for this article.

In an August White House blog post, OMB and the Treasury Department reflected on progress made, such as finalizing uniform definitions for data fields. The standards provide “a foundation to improve the quality and consistency of data available on USASpending.gov,” wrote David Mader, OMB’s acting deputy director for management, and David Lebryk, Treasury’s fiscal assistant secretary. “We have taken an important step to provide valuable, usable information on how tax dollars are spent, who they are spent on, and for what purpose.”

Previously, in a May blog post, the pair praised the Health and Human Services Department for taking the lead in the grant reporting experiment. The department has prescribed data categories that should be used to break down all grant funds, like “federal share” and “highly compensated officer name.”

As of October, the administration was still discussing how to conduct a contractor spending study.

The vagueness of the phrase “open government” has played into perceptions of Obama’s success in achieving the ideal, some researchers say.

“I think openness meant whatever the listener thought or hoped that it meant. This generated unrealistic expectations, followed by disappointment and even cynicism,” says Steven Aftergood, who directs the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists.

Individual departments, for the most part, have abided by different principles of transparency, experts note.

You can’t have transparency without embarrassment.

earl devaney, former recovery board chairman

“Progress in openness has depended on personal leadership from senior agency officials,” Aftergood says. One unlikely example he tosses up is the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Robert Cardillo, director of the spy mapping agency, facilitated the posting of unclassified data sets related to Ebola aid, the Arctic, piracy and other subjects. “Where leadership is missing, transparency has stagnated,” Aftergood adds.

In the end, the determination of agencies—or lack thereof—may define Obama’s record on data transparency.

Sean Moulton, open government program manager at the Project on Government Oversight, says top administration officials likely still want to present as much data as is legal, but they have lost the willpower.

“They came in and they found out that it was a lot harder, a lot slower and a lot more expensive to change the entrenched culture of government, than I think they imagined,” Moulton says. When the DATA Act was proposed, administration officials grew gun-shy, reluctant to charge into agencies and announce “it’s a governmentwide spending transparency thing with tight deadlines,” he adds.

Many top administration officials probably would wave a magic wand if they could and compel agencies to follow through on open data policies, despite the potential for public shaming, says Moulton, who co-developed the precursor to USASpending, a grassroots website called FedSpending.org.

But there are concerns, especially among well-heeled, large agencies, about how the information might be used, ways it could be correlated with other details, and whether it will make them look bad, he says. There might not be “some smoking gun that they are trying to hide,” Moulton adds, “but I think to some extent they don’t even know what the data will say.”

Aliya Sternstein reports on cybersecurity and homeland security systems. She’s covered technology for more than a decade at such publications as National Journal's Technology Daily, Federal Computer Week and Forbes. Before joining Government Executive, Sternstein covered agriculture and derivatives trading for Congressional Quarterly. She’s been a guest commentator on C-SPAN, MSNBC, WAMU and Federal News Radio. Sternstein is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania.