Two weeks after being sworn in as secretary of State, Hillary Clinton gathered hundreds of employees together in the Dean Acheson Auditorium at department headquarters in Washington.

“Some of you may know that I like to conduct listening tours,” she told those present or watching on closed-circuit TV on Feb. 4, 2009. “It’s something I started back in the 1980s when I was first lady of Arkansas. I continued it in New York and around the country. I found that meeting with people and listening to their concerns in small groups and large was very important to me and gave me a lot of excellent ideas and constructive criticism.”

In this first of 60 town halls or “town interviews” held over four years, Clinton announced a plan for an online suggestion box, adding, “I take the responsibility of managing our department and obtaining the resources necessary to fulfill our missions very seriously.”

What struck Melanne Verveer, a longtime Clinton confidante and White House executive, about those meetings was that people felt that they could talk to the secretary of State about their children or seek career advice.

“She was genuinely popular at State and always took questions, not just for the political leaders, but about what things mean for the rank and file,” Verveer told Government Executive. “Large numbers of people were teary-eyed on her last day,” said the first U.S. ambassador-at-large for global women’s issues. It was “a very emotional time.”

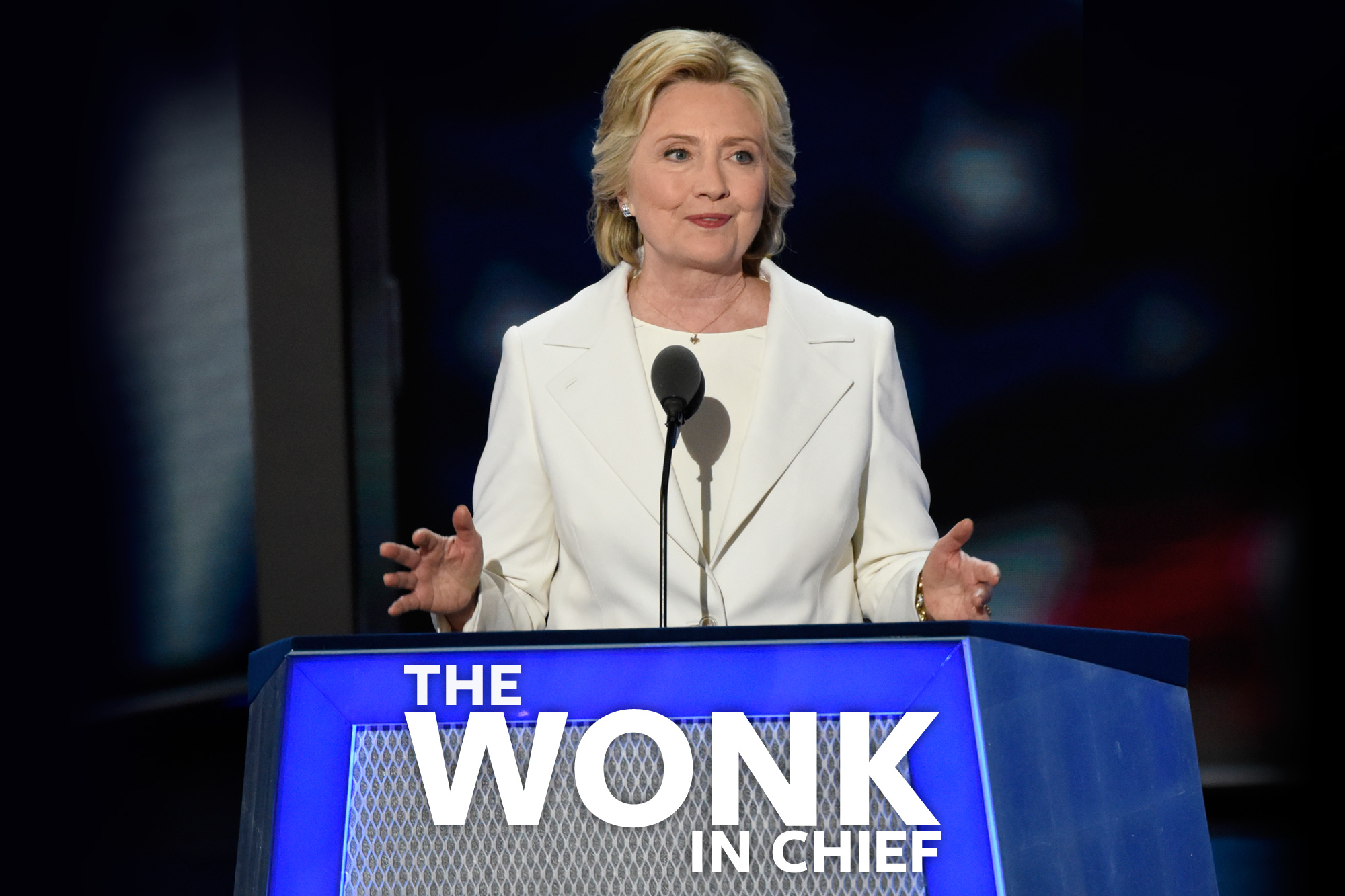

Generally, Clinton was well liked by the career denizens, agreed Ray Arnaudo, a retired State Department official who was on the policy planning staff. He said Clinton always struck him as “well-prepared in running meetings, and unlike many other secretaries, she had actually read the memos we sent her.” As she stated in her July 28 acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, she prefers to “sweat the details” of policy.

During her tenure running the government’s oldest department, however, Clinton spent relatively few days in Washington. She flew a million miles in 2,000 hours over 400 days to visit 112 countries, as she recalled in her 2014 memoir Hard Choices.

Clinton’s resulting accomplishments, as selected by her presidential campaign for a June TV advertisement, included negotiating a cease-fire in Gaza, reducing the global stockpile of nuclear weapons, taking on Russian President Vladimir Putin and fighting human trafficking. A list to which one must add her taking the lead on the Obama administration’s much-discussed “pivot to Asia,” which was first laid out in a 2011 Foreign Policy article by Clinton. There was also her successful push for the department’s first-ever Pentagon-style Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review in 2010, which she described as a plan for “harnessing new technologies, public-private partnerships, diaspora networks and other new tools, and it soon carried us into fields beyond traditional diplomacy, especially energy and economics.”

Clinton’s public approval ratings—tracked by the Pew Research Center since the early 1990s—reached their peak at 66 percent in 2009, early in her tenure at State. Annual Federal Employee Viewpoint surveys conducted by the Office of Personnel Management showed that during her first two years, Clinton managed to raise rank-and-file appreciation for leadership (though it tapered off in her final years).

But critics—and there were many who declined to be interviewed—found plenty of blades with which to cut Clinton down to size. There was the debacle surrounding the deaths of four Americans in 2012 at the U.S. diplomatic compound in Benghazi, Libya, and the “reset” with Russia that was overtaken by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression in Ukraine and Syria.

Hillary Clinton testifies on Oct. 22, 2015, before the House Benghazi Committee. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

“Like Hillary Clinton, I too have traveled hundreds of thousands of miles around the globe,” said then-GOP presidential candidate Carly Fiorina in February 2015. “But unlike Hillary Clinton, I know that flying is an activity, not an accomplishment.”

Clinton’s mishandling of official email using a private server during her tenure at the State Department continues to dog her, as well as some murky intersections between her official meeting schedules and those of donors to the Clinton Foundation set up by her husband, former President Bill Clinton.

Some resented the personnel powers of her “entourage,” including Chief of Staff Cheryl Mills and Deputy Chief of Staff Huma Abedin, both longtime residents of “Hillaryland”—a phrase coined inside the White House—going back to the 1990s, when Clinton became the first presidential spouse with a policy portfolio.

Huma Abedin, aide to then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, goes over notes with Clinton during her visit to Zambia on June 11, 2011. Clinton was on the first leg of a three-nation tour of Africa. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh, Pool)

If Clinton becomes the first woman to occupy the White House, she will bring a unique background and no small amount of baggage to the job. The former first lady, senator for New York and secretary of State built a career advocating for children and families, yet she engendered, alone and with her husband, countless ethics scandals. And she maintains stubbornly high levels of mistrust among voters.

What is clear from her performance at State is that Clinton views government—particularly when she has a personal role in it—as a force for good. In her 1996 book It Takes a Village she made an observation that probably holds today: “Despite the resurgence of anti-government extremism, it is becoming clear that most Americans do not favor a radical dismantling of government. Instead of rollback, they want real reform.”

A Clinton victory in 2016 wouldn’t guarantee she could mobilize politicians and agencies to ease what many call Washington’s dysfunction. But there can be little doubt that a Clinton administration would try.

The Likely Agenda

During her first 100 days in office, Clinton would propose $275 billion (“the biggest investment in jobs since World War II”) in spending on roads, bridges, tunnels, ports and airports, she has said on the campaign trail. That would include $25 billion in seed money to create a national infrastructure bank in Washington (as proposed by President Obama, without effect). If enacted, that package would presumably require a revival of the Economic Recovery Advisory Board to track spending and catch fraud.

Immigration reform is another area Clinton has championed. Legislation she has supported would expand security and legalization resources at the Homeland Security Department’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services agencies.

Her lifelong advocacy for women and children might mean initiatives resembling Obama’s call for pre-kindergarten education, which Clinton endorsed, and expanded child care aid through the tax code and the Health and Human Services Department’s Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting program. A Clinton Labor Department would take new initiatives in funding union training and apprenticeships. And she would oppose Republican efforts to abolish the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

To develop and retain talent in the federal workforce, Clinton might push a proposal she introduced as a senator in 2007 to create the first-ever U.S. Public Service Academy. It would provide an “annual influx of career-motivated public servants and future leaders into the nation's public institutions,” a summary said, and “provide competitive, federally subsidized, public service-focused undergraduate education to students from across the United States and the world.”

Then-Sen. Hillary Clinton, a Senate Armed Services Committee member, asks a question on May 22, 2008, during a committee hearing. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

Clinton would also carry on Obama’s quest for “smarter and more innovative government.” Her technology plan, released by the campaign on June 30, calls for making agency websites more user-friendly to improve customer service. It would make permanent the U.S. Digital Service while expanding it from the White House to other agencies. And “she will maintain support for other federal tech programs—18F, Innovation Fellows, and Innovation Labs—and look to them to develop a coordinated approach to tackling pressing technology problems.”

Like her predecessors, Clinton promised to streamline procurement, including breaking “large federal IT projects into smaller pieces, so it will be easier to stop projects that are over budget or failing to meet user needs, and also more feasible for small and medium-sized businesses to support public service projects.”

Clinton said she would continue the push for open data, especially in the regulatory agencies. And she would beef up cybersecurity by prioritizing “enforcement of well-known cybersecurity standards, such as multifactor authentication, as well as the mitigation of risks from known vulnerabilities.”

Judging by her Senate record, Clinton would likely continue Obama’s push for paid parental leave for federal employees. And she would preserve equal government benefits for those in same-sex relationships, one of her chief legacies from the State Department. During one of the town meetings, Clinton recalled in her memoir, a Foreign Service officer emotionally thanked her for opening the door to his career: “The moment you directed the department to recognize same-sex spouses as family members, the one thing that had been holding me back was suddenly no longer standing in the way.”

Tactics and Style

After decades in public life, Clinton has accumulated a vast network of political and policy relationships here and abroad—many in unexpected quarters. At State, she famously bonded with Defense Secretary Robert Gates. In his 2014 memoir, Duty, he wrote, “I found her smart, idealistic but pragmatic, tough-minded, indefatigable, funny, a very valuable colleague, and a superb representative of the United States all over the world.”

Among the military, Clinton worked closely with Army generals David Petraeus, Jack Keane and Stanley McChrystal on such issues as whether to send more troops to Afghanistan. Before embarking on a bid to open ties with the closed country of Burma, she first ran it by Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., as noted by New York Times reporter Mark Landler in his 2016 book Alter Egos.

Most reviews of her tenure as senator credit her with cooperating with Republicans on such issues as securing federal relief for first-responders following 9/11. But she may not have helped prospects for “reaching across the aisle” when, asked to name her enemies during an October 2015 Democratic debate, she included Republicans.

A delegation of senators view the rubble of the World Trade Center on Sept. 20, 2001. From left, Senate Minority Leader Trent Lott, Sen. Hillary Clinton, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, Sen. Charles Schumer and Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle. (AP Photo/Mike Albans, Pool)

More than any previous president, however, Clinton would likely tap into her network of sisters breaking glass ceilings, both for appointments to top jobs and for policy choices in areas like the family-friendly workplace. “I suppose I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas,” she famously told a reporter during the 1992 presidential campaign. “But what I decided to do was to fulfill my profession, which I entered before my husband was in public life.” In April, she told Cosmopolitan she would appoint a diverse Cabinet, half of which would be women: “Since we are a 50-50 country, I would aim to have a 50-50 Cabinet.”

Clinton’s famous declaration that “Women’s rights are human rights,” spoken as first lady at the September 1995 United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, still reverberates: The Voice of America last year showcased it in a video “A Single Step” on women’s economic status in the developing world.

First Lady Hillary Clinton delivers a speech to the Fourth Women's Conference in Beijing, China, on Sept. 5, 1995. (Clinton Presidential Library)

Former ambassador Verveer said Clinton “never ran into sexism at State and never talked about the issue.” But the reason for “interpreting things through a gender lens” in, for example, the Quadrennial Review, was “for effectiveness, jobs and prosperity,” Verveer said. “The issue received tremendous support and great receptivity because no country will get ahead if it leaves half its people behind.”

Clinton’s elevation of such “soft” social issues to the level of warfare and treaty negotiations, however, left openings for critics. “Clinton tended to settle for too little and squandered her influence on the small stuff,” wrote diplomat-turned-Northeastern University professor Mary Thompson-Jones in her 2016 book To the Secretary. Bravo for her bringing clean cook stoves to the Third World, “but was this the highest-value use of her time?”

The emergence of an anonymous Twitter critic of Clinton on the White House National Security Council staff (Jofi Joseph was eventually fired) prompted journalist Landler to conclude that the harsh tweets were “simply voicing what a number of people in the White House and State Department privately thought: Hillary Clinton had been a respectable but run-of-the-mill secretary of State.”

Managing Scandals

Clinton has grown accustomed to fielding ethics accusations from political opponents and the press, which would likely be one of the central management challenges of a new Clinton administration.

Lingering questions about her secrecy, truthfulness and responsibility for insufficient security at the U.S. consulate in Benghazi—the subject of nine investigations—stuck in part, critics said, because she insulated herself from State’s Accountability Review Board probe of the incident, which did not include interviews with her.

Clinton did, however, appoint the board and later agreed to implement all of its recommendations to improve protections of overseas personnel. And she released an unclassified version. “We’ve got to live in a transparent age, and we’ve got to be willing to get out there and own what we do and constantly work to improve it,” she told employees in 2013, encouraging the agency to “shed our defensiveness.” Her critics would argue that her failure to heed her own advice is the source of many of her biggest problems.

Nowhere is that more apparent than with the controversy over her private email server, which put classified information at risk and flouted Freedom of Information Act guidelines. The existence of the arrangement wasn’t disclosed until media reports more than two years after she left State. To Clinton’s doubtless embarrassment, one of the emails later disclosed was a 2011 departmentwide memo from her instructing employees to avoid conducting official business on personal email accounts.

Clinton’s assertion that she set up the server for convenience—a move she since has acknowledged was a mistake—didn’t clarify who among the department’s legal counsel, records management specialists and information technology staff gave the green light. (Her personal attorney David Kendall later told a judge that the setup in her New York home “was clearly permitted and allowed,” but he admitted it was never specifically approved by anyone.)

Both the Benghazi and email episodes speak to Clinton’s tendency not to “sweat the details” when it suits her. But these issues “are bigger than Clinton and the State Department,” Verveer said. “At all agencies, the secretary is ultimately the responsible agent, but they can’t possibility deal with what’s on their plate every day. There are management protocols, but they can’t be micromanagers—they have to depend on people who handle security, management and the building. You think all is being done, but often you find things have been lacking.”

Former acting CIA director Michael Morell, who endorsed Clinton for president, said on ABC’s This Week Aug. 7, that “Clinton would be the first to tell you the processes and systems of the State Department for handling classified information need to be enhanced.” And those reforms would apply across government, he continued, with her in the White House.

During her final town hall meeting at the State Department, on Jan. 30, 2013, Clinton was asked to look back on her tenure. Her answer could take on deeper meaning in January:

“I walked into the door of the State Department more than four years ago now, determined to elevate diplomacy and development as pillars of our foreign policy alongside defense because I was convinced they were critical for solving problems and seizing opportunities worldwide,” she said. “And I will walk out the door this Friday even more convinced of that because of the work that we have done together during some challenging and even tumultuous times.”