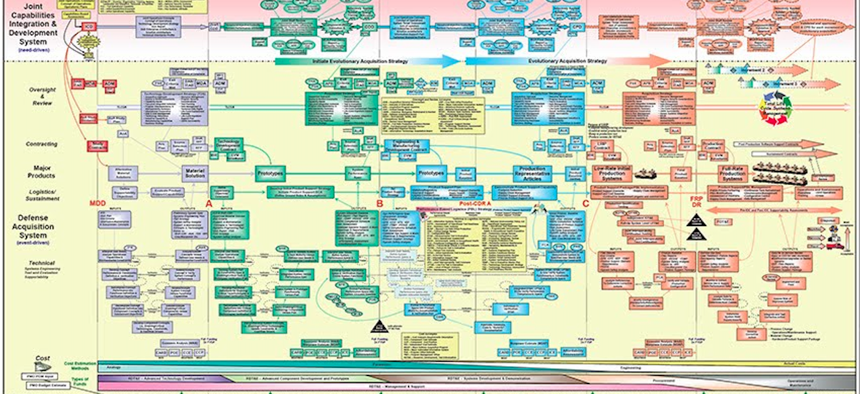

Photo credit: Defense Acquisition University

Defense Acquisition Reform: Is Something Different this Time?

Defense acquisition reform has recently become a hot topic again for the defense community. Though acquisition reform has been attempted again and again over the last 50 years, circumstances today suggest structural reform may actually be possible now.

Acquisition reform initiatives are hardly novel for the Department of Defense, but the circumstances giving rise to renewed calls for structural reform suggest this time may be different. At a recent American Security Project event, Norm Augustine, former CEO of Lockheed Martin Corporation and Undersecretary of the Army, described three factors driving his belief that the time is finally ripe for reform.

First and foremost, the specter of sequestration - despite temporary, partial relief - means the department must prepare to make do with a shrinking budget. As Pentagon officials scour accounts to find sources of cost savings, the acquisition process sticks out as an area where purchasing power can be greatly improved. A recent GBC study helps show why. A survey of 340 DoD managers found 42% believe cost is a major acquisition problem, while 58% indicate it is a major problem for C4ISR acquisition. A new GAO report offers more detail, demonstrating that 45% of of the $682 billion needed for future acquisition funding represents cost growth over original estimates.

Second, the pace and breadth of technological change has accelerated in recent years, and the acquisition process has had trouble keeping up. New developments in cloud computing, mobile technology, cybersecurity, and C4ISR provide regular proof of this, but acquisition inertia has also proved problematic for less sophisticated developments. For example, more than five years after invading Iraq, former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates found it necessary to circumvent the normal acquisition process and set up a special senior-level unit - the Counter IED Senior Integration Group - just to acquire appropriate equipment to protect U.S. troops from Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs).

Finally, an increasingly diverse and uncertain threat landscape - partly generated by technological change - affirms that DoD will need to expand capabilities while maintaining more traditional ones. Augustine reiterated what the Pentagon’s 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review made clear: the U.S. military will need to sustain traditional force projection means, maintain counterinsurgency capabilities developed over the last 12 years, and invest in emerging technologies to ensure superiority in a new and more uncertain era of defense.

So what should reform look like? Augustine’s comments and the aforementioned GBC study suggest two essential guidelines:

- Bring different sets of stakeholders closer together. Despite recent improvements in the requirements development process, operators, engineers, and acquisition professionals remain too disconnected. Greater integration of these groups can help ensure the acquisition process supplies warfighters with the best systems in the most cost-effective manner.

- Tie acquisition programs more closely to budgets and strategic priorities. DoD tends to plan acquisition programs one by one and without matching goals to resources. As a result, programs can morph into larger programs that take longer and cost more than originally intended. Impactful acquisition reform would require programs to be planned concurrently and in sync with clear budgetary parameters. Moreover, acquisition programs could be made more difficult to both initiate and stop so that DoD plans its programs more strategically.

More so than before, DoD is well-positioned to undergo structural acquisition reform. As Augustine said, the silver lining of being in tough times is that the tough decisions are that much easier to make.

This post is written by Government Business Council; it is not written by and does not necessarily reflect the views of Government Executive Media Group's editorial staff. For more information, see our advertising guidelines.