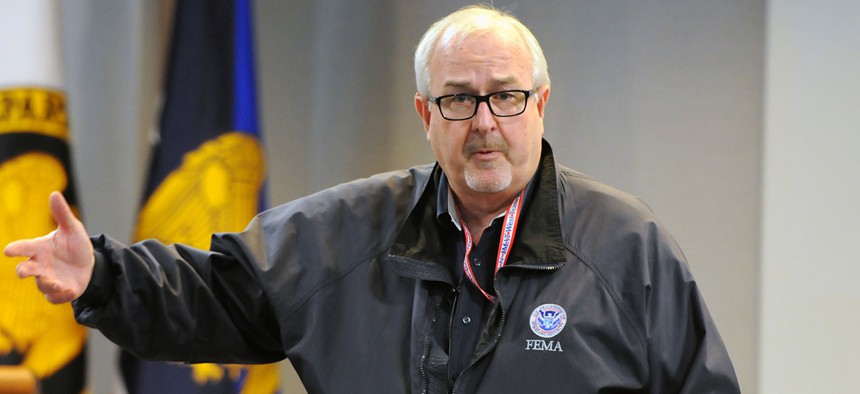

Craig Fugate spoke at the winter National Guard Senior Leader Conference in Virginia in February. Sgt. 1st Class Jim Greenhill/Army

How FEMA Director Craig Fugate Wants to Reshape Disaster Management

Fugate on why the Katrina response failed, why it’s important to talk about “survivors” instead of “victims,” and why citizens can’t just wait for the government to save them in a huge disaster

If you’ve never heard of Craig Fugate, that’s probably best for all involved. Most people only know the names of directors of the Federal Emergency Management Agency when something goes badly wrong—just ask Michael “Heck of a Job” Brown, who led the organization during Hurricane Katrina. “My joke has been my entire career, I’m that individual when things go south. You gotta fire somebody, so I’m the guy you’re gonna fire,” Fugate says.

Since his appointment and confirmation to lead FEMA at the start of the Obama administration, Fugate has been largely out of the public eye. That’s despite several major disasters, including Hurricane Sandy and a string of deadly hurricanes in 2011. (In fact, 2011 saw an unprecedented 99 federal major disaster declarations.) Within the emergency-response community, however, he’s well-known for his philosophy of “whole-community response,” which seeks to decentralize disaster management from the federal government and involve the private sector, volunteers, and private citizens. The idea is aimed at solving some of the glaring weaknesses in how the government responds to disasters, flaws that were exposed most clearly by Katrina.

“Craig was absolutely revolutionary with the whole-community thing,” says Russ Paulsen, executive director of community preparedness and resilience services at the American Red Cross. “Before Craig started talking about whole community there really was this view that there's emergency responders, and there's the rest of us, and ne'er the twain shall meet. This idea that really we can all play a role in emergency response was both revolutionary and very helpful.” (Barack Obama, speaking in New Orleans last week, was blunter: “I love me some Craig Fugate,” he said.)

Fugate—who began his career as a volunteer firefighter and eventually rose to lead the Florida Division of Emergency Management—offered a somewhat self-effacing view of how he's trying to change the response mentality during an interview at his office in Washington. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

David Graham: Everyone I talked to spoke very highly of the idea of whole-community response.

Craig Fugate: It’s nothing innovative.

Graham: All these professionals say so!

Fugate: If you talk to people that are really in this business, it’s nothing revolutionary. In fact, most of the people look at me and say, “What the hell are you calling it, ‘whole community’?”

When people talk about catastrophic disasters, it’s kind of an abstract term. [In Florida] we tried to put it into, what has happened historically that would hit that threshold? The Great Miami Hurricane in the ’20s, extrapolated out for today’s dollars, it’s about a $120 to $130 billion storm. We had all these organizations, including a lot of faith-based and volunteer groups; we had the business community; we had the government agencies, both local and state and federal partners. We kept talking about how we were going to take care of the 6.8 million people that had been devastated by the storm, the number of houses that were destroyed, the power outages, everything else. The numbers were staggering. There’s a demand that there’s no way this group’s going to be able to address. I kept thinking about it for a minute. I’m going [pause], “What happened to the 6.8 million people? Did they just, like, get sucked up by aliens? Why are they not part of this?” We had almost by default defined the public as a liability. We looked at them as, We must take care of them, because they’re victims. But in a catastrophic disaster, why are we discounting them as a resource? Are you telling me there’s not nurses, doctors, construction people, all kinds of walks of life that have skills that are needed? “Post-traumatic stress” was this huge thing we had created to describe what people are going through in disasters, and how disasters are so traumatizing and leave lifelong scars, but when you started reading the research, it said for most people that’s not what happens. Certain symptoms you go through are quite normal, and we should be normalizing that, not making it exceptional. The best way to reduce the long-term impact is to get people back in control.

Our response was literally to take all the control away from them. I took some of the language that I started seeing in the mental health and behavioral sciences of, “Quit referring to people as victims and call them survivors.” I said, my first goal is to change the vocabulary of emergency management. As long as you use vocabulary like “victims,” you’re going to treat the public like a liability and you have to take care of them. That works in most small- to medium-size disasters, ’cause we can bring in more help than there are people—but the bigger the disaster the less effective it is. When you step back and look at most disasters, you talk about first responders—lights and sirens—that’s bullshit. The first responders are the neighbors. Bystanders. People that are willing to act.

When we were in Joplin, there was a gentleman there, and the president says, “Were you here?” He describes all this stuff, how the tornado destroyed his house and he barely survived, and the president says, “So what’d you do?” And the guy looks at the president like [puzzled face], “I went and started helping people dig out. My neighbor was screaming for help.” The president says, “Sir, do you mind me asking how old you are?” And he’s in his eighties. It was not an isolated case. The most effective response you’ll get is just a simple request: “Once you do all the stuff you’re supposed to do, check on a neighbor.” It’ll save more lives than anything else we can do.

Graham: Were people doing this on their own? Was FEMA in the way?

Fugate: Yes. It was getting in the way—not FEMA physically all the time, but in the way we wrote our plans and the way we did our training. What we built was government-centered problem solving. Everything was built on what government was going to do because the expectation from the media and everyone else was,The government’s going to be in charge and if anything goes wrong, it’s the government’s fault, so therefore the government’s gotta fix everything. This is a kind of creepy thing I sometimes run into in the response community. It’s all about the person that’s doing the rescuing. It’s like … No! It’s all about the people we’re trying to help. If that makes you feel good, great. But the reason you’re doing it isn’t to feel good—it’s to address what they need, but also to empower them and give them control.

Graham: Where did that mentality go wrong? Was there a response that didn’t go like it should have?

Fugate: A classic one is housing. We thought the mission was to provide people housing, and then we couldn’t figure out why when we changed administratorswe had over 5,000 people still living in travel trailers. We defined the mission as getting everybody in temporary housing. No one defined it as, “How do we provide long-term, stable housing?” As much as people criticize the housing that was provided, the reality was, almost five years after Katrina, you still didn’t have good options. I know of no community that did not have affordable-housing issues before a disaster, and none of them got better—they always got worse.

You’ve got a lot of people who think they’re middle class but they’re really on the margins. They’re one catastrophe away from losing everything, ’cause most of their equity was in their house. You can’t build houses that fast, so you gotta have both a bridging solution, which is what FEMA’s role is, but you also gotta take a step back and go, “What’s in the best interest of the public?”, and look at fromHUD and all the other things we do, how are we going to work with state and local governments, because they have an equity in this, and the business community has an equity in this: How are we going to get affordable, stable housing for the workforce?

Graham: The Waffle House thing, right? [Ed.: Fugate has often spoken about the “Waffle House index,” the idea that the scale of a disaster, at least in the south, can be measured by how fast the breakfast chain reopens. The longer it takes before you can get an All-Star breakfast, the worse the situation is.]

Fugate: The Waffle House thing. Oftentimes if you do government-centered planning you forget about the private sector unless you need them to do something for you. We’re asking a different question: “What can we do to get you open?” Each level of government, they do things that they think intuitively are helpful to recovery, but may be counterproductive, like curfews. When you talk to big-box retailers, they do almost all their resupply at night. Yet, your curfews are generally at night. So you have this mismatch between law enforcement trying to keep an area secure at night and the private sector saying, “But that's when we try to do our resupply, when we try to do our repairs.” [Law-enforcement officials] say, “We’re trying to reduce looting, lawlessness, and all that.” I’m like, what do you think is going to happen when stores aren’t open and there’s nowhere to get stuff, versus there’s a lot of stores open and people can start taking care of their own needs?

Graham: What are the implications of whole-community response for disasters like Katrina?

Fugate: When people talk about Katrina, they always want to go, “What happened, what went wrong in Katrina? Well, FEMA screwed up, Mike Brown screwed up, the mayor got ...” The systemic problem was we planned for what we were capable of responding to, not what could happen. And when the system and the impact was greater than that, it failed. The whole community and all this other nonsense that all these people think is new and radicalized, it's like, guys, this is pretty basic stuff. But it does force us into thinking about disasters where government-centered problem solving will fail when our communities need us the most. That forces us to make a decision: Do you plan for what your average response looks like, or what you're capable of doing—or do you plan for the hazards we face as a nation and understand every part of a national response at all levels of government, the private sector, volunteer and faith-based communities, and the public?

NEXT STORY: It’s Time to Rethink the Way Work Is Managed