Senior Executive Service Faces ‘Pivotal Moment’ on Cusp of Next Administration

Report details some agencies’ efforts to infuse new life into the frail, aging elite career corps.

This story has been updated.

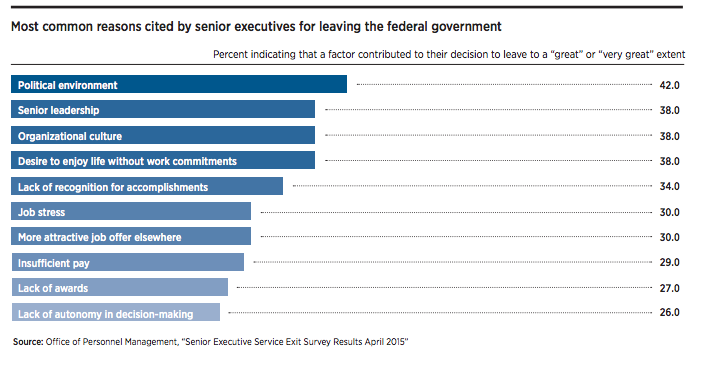

The Senior Executive Service, older and less diverse than the rest of the federal workforce, faces serious challenges recruiting talented managers who view the government’s top career jobs as prestigious but basically a headache. And yet, according to the new report, there are several examples of federal agencies using creative approaches to improve the elite corps as the government prepares for a new political administration.

The ideas range from relatively simple (arranging monthly meetings for senior executives to network and commiserate in person and via technology) to extraordinarily complicated (moving to an entirely resume-based SES hiring system), but they’re having a positive effect on recruiting and retaining top career officials, said dozens of people inside of government interviewed for A Pivotal Moment for the Senior Executive Service, a new report on the health and future of the SES.

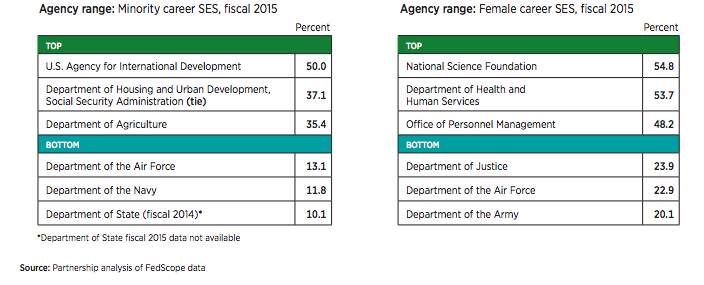

The report, conducted by the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service and management consulting firm McKinsey & Company, offers some bleak SES statistics: 85 percent of the corps is eligible to retire in the next decade, while less than 60 percent of current top managers in the General Schedule actually aspire to the SES ranks. And while the SES is more diverse than the executive ranks of the private sector, it still lags behind the rest of the federal workforce: Women made up 33 percent of the career SES in fiscal 2015 compared to 42.5 percent of the federal workforce; minorities made up 20.5 percent of the top career cadre and 36 percent of the federal workforce in fiscal 2015.

But agencies are trying to revive and diversify the SES, which has drawn more attention in recent years thanks to management scandals at the Veterans Affairs Department and President Obama’s 2015 executive order aimed at reforming the institution.

For instance, Customs and Border Protection and the General Services Administration have both shifted to resume-based hiring for the SES, and officials report more transparency, better applicant data and trends, and a stronger pool of applicants. Many SES candidates have complained that the lengthy written responses they have to produce to demonstrate executive core qualifications are a deterrent to the hiring process, but agencies have been reluctant to get rid of ECQs for fear of attracting a dramatic influx of SES applications that they couldn’t handle, or a less qualified group of candidates. But giving second-round candidates problem-solving assignments and implementing behavior-based interviewing (which forces applicants to explain how they handled specific work situations in previous jobs) have helped ease the ECQ burden on applicants, while still helping to target the best people for the job, the report found.

Some agencies, like NASA and the Army Department, have reviewed their top career positions and decided which required more executive management skills, and which needed more technical expertise to match the right people to the right jobs. The Army, for example, requires only one technical qualification for entry-level SES jobs, and none for mid-to-senior level SES positions, according to the report.

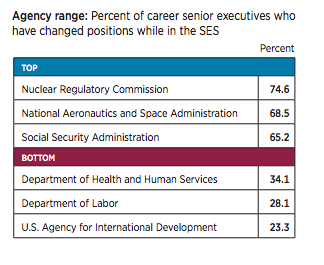

Agencies also are trying to make the SES more mobile to ensure the corps is flexible, has experience working in different environments, and is well-versed in a variety of federal management challenges. The SES was designed to be more agile, with executives moving around to other jobs and agencies within the government over the course of their careers.

“People learn when they are pushed outside their comfort zones…I know that the best learning happens from those difficult experiences that you probably wouldn’t ask for,” one interviewee said in the report, which administration officials will gather in Washington to discuss on Wednesday during an event hosted by PPS.

Easier said than done. Several things over the years have thwarted the goal of a nimble SES: people’s reluctance to uproot to another geographic region, performance management systems that aren’t standard across agencies, and a lack of transparency into the rotational assignment decision-making process. Fifty-three percent of career senior executives have not changed jobs while in the SES, according to fiscal 2015 data from the Office of Personnel Management cited by the PPS report.

The Army requires senior executives to move into new jobs every five to seven years, and has tried to improve the process by creating a more transparent talent management board made up of people and groups outside the department who weigh in on rotational assignments. Human resources plays an important role in outlining expectations for senior executives in new jobs. And the department tries to collaborate with other federal agencies in the same geographic location to help SESers change jobs while staying in a specific geographic region.

Agencies also realize that they have to do a better job making meaningful distinctions among senior executives when it comes to performance evaluations, which determine everything from bonuses to morale. A January 2015 GAO study found that about 85 percent of career senior executives received “outstanding” or “exceeds fully successful” ratings in their performance reviews between fiscal years 2010 and 2013, concluding that most federal agencies were not making meaningful distinctions in performance ratings and bonuses for senior executives.

“Some agencies have begun to address the lack of data and improve performance management by focusing on performance alignment – the connection between an individual’s performance goals and agency goals,” the PPS report stated. “Some are also using electronic performance management systems, such as inCompass, enabling employees to see connections between their individual performance goals, their senior executives’ performance goals and agency strategic goals.”

In other cases, just the opportunity to observe a leader in the midst of a management crisis can prove invaluable to potential recruits, the report found, illustrating the practice of “shadowing” at some agencies. Employees were shadowing NASA Administrator Charles Bolden in 2013 during the battles over the impending government shutdown, the report recounted, adding that Bolden let the observers stay in the room while he took phone calls from Capitol Hill and the Office of Management and Budget. “These types of experiences have the potential to change people’s careers,” Keith Lowe, NASA’s lead for hiring, recruiting and compensation, told report interviewers.

A simple “thank you” can go a long way too, according to Reginald Wells, the Social Security Administration's chief human capital officer, who told report interviewers about an event hosted in Los Angeles, Calif., for outstanding senior executives by that region’s Federal Executive Board. “Some of the people in Los Angeles were on the verge of tears,” Wells said. “One woman said she had never been treated this well, and all we did was host a luncheon, read her biography, and give her a medal. It really does speak to the intrinsic value of doing these kinds of events.”

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly stated that Reginald Wells is the Education Department CHCO. He is the chief human capital officer at the Social Security Administration.

NEXT STORY: NASA Finds That the Earth Has a New 'Mini Moon'