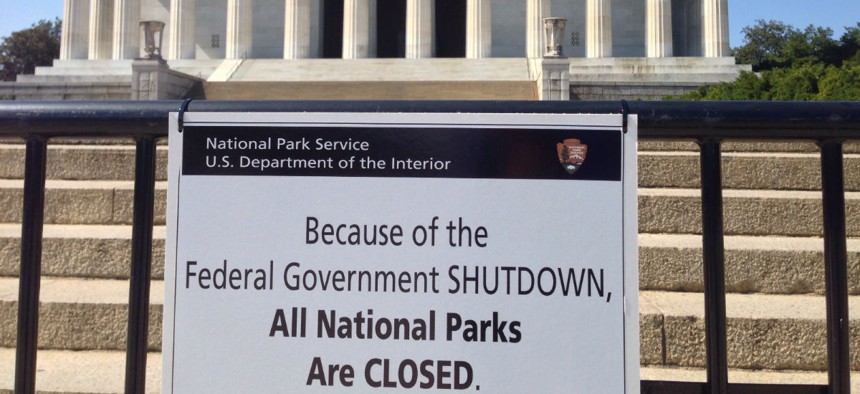

Flickr user John Sonderman

Study: Furloughing Feds in 2013 Shutdown Produced Significant Economic Drag

Forcing federal employees not to work took billions of dollars out of the economy.

Federal employees worked 6.6 million fewer hours during the 16-day government shutdown in October 2013, according to a recent report, with the loss of productivity resulting in a 0.3 percent loss in economic growth.

In other words, sending more than 850,000 federal employees home without pay for at least part of the shutdown took billions of dollars out of the economy.

In an analysis released this month measuring the effects of the shutdown, the Congressional Research Service said while federal spending -- including the retroactive pay to furloughed employees -- was eventually restored and made up for, the loss of work hours could not be similarly reinstated. The “supply” created by the government was irreversibly diminished, CRS said, as furloughed federal workers could not contribute to the production of government output while out of work.

The analyses of the overall economic impact of the shutdown that CRS examined produced varying results, though they all indicated some negative effect. Standard & Poor’s said the shutdown shaved 0.6 percent off growth in the fourth quarter of 2013, effectively taking $24 billion out of the economy. Others estimated a 0.1 percentage point reduction in growth of the Gross Domestic Product for every week the shutdown carried on.

Some analysts looked more precisely at the impact caused by furloughing federal workers. Morgan Stanley estimated the compensation of the civilian workforce accounts for 1.5 percent of GDP. The company predicted a 0.15 percentage point reduction in GDP growth for each week the shutdown lasted, assuming one-third of employees were sent home.

While about 40 percent of civilian federal employees were initially furloughed when the agencies were forced to close starting Oct. 1, the Defense Department recalled nearly all of the 400,000 civilians it originally sent home several days after the shutdown began. That action caused Goldman Sachs to reduce its initial estimate of the economic drag of the appropriations lapse.

CRS noted those estimates should be thought of as the “lower bound” of the overall effects on economic activity, as they did not account for more residual, indirect impact of the shutdown. While the overall damage caused was relatively small due to the length and boosted federal spending that resulted when government reopened, the shutdown “created hardships for some of those directly affected by it,” CRS said.

For example, federal employees may have “reduced consumption” based on their delayed pay. Additionally, federal workers and contractors -- a number of whom unknown to CRS were also furloughed -- may have seen an “uptick in delinquencies” due to their delayed pay. That could hurt their creditworthiness, thereby reducing household wealth and spending. The issue could have affected even the 1.2 million federal employees forced to work during the shutdown, who were guaranteed back pay but only once the government reopened.

The shutdown had an obvious, immediate impact on employment. The week before agency funding expired, about 1,400 feds filed for unemployment compensation. During the shutdown, that number spiked to 70,000, according to CRS. Many furloughed federal employees initially received unemployment compensation, but after Congress approved back pay, the Labor Department issued a rule demanding they pay it back.

Congress has until the end of Sept. 30 to reach a deal to fund agencies and avoid a shutdown. The Senate is now expected to take the lead on a stopgap continuing resolution after it votes on a doomed measure to defund Planned Parenthood. A so-called clean CR would likely pass the Senate with the support of some Republicans and all Democrats and has the White House’s backing, but its fate in the House is still unclear.

(Image via Flickr user John Sonderman)