Silicon Valley May Soon Offer a Public Bus Commute That's Quicker Than Driving

A VTA bus could be the solution. Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority

The El Camino BRT project shows why great transit needs exclusive lanes.

The big advantage of driving to work over taking the bus is time. A bus ride just takes longer: walking to the stop, waiting for the bus, picking up passengers, all while toughing out the same traffic as cars. But when transit is done well, the time gap shrinks, and when it's done really well—with frequent service, all-door boarding, and exclusive lanes—the gap can disappear entirely.

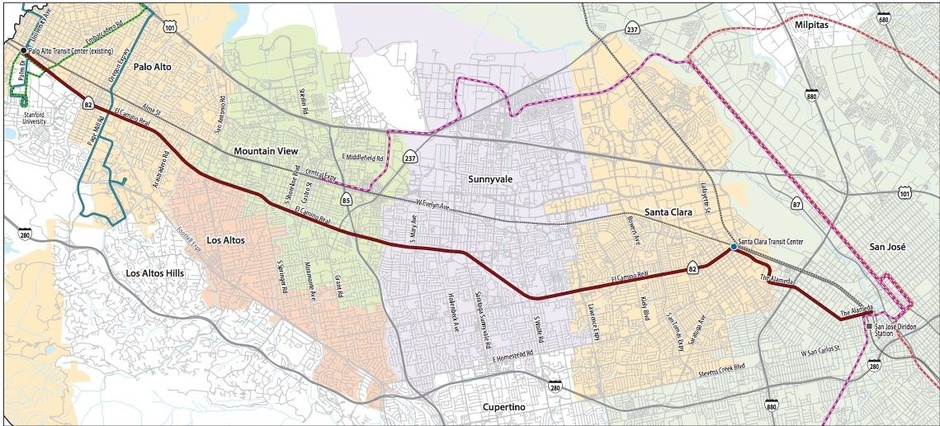

Silicon Valley ( of all places ) may offer a sparkling example of how buses can compete with cars in the not-too-distant future. The Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority has released a draft environmental review for a 17.6-mile bus-rapid transit line on El Camino Real connecting San Jose with Palo Alto (home of Stanford) via Mountain View (home of Google). In the plan's best-case scenario, the El Camino BRT would travel the corridor almost as quickly as cars by 2018, when the line hopes to open, and occasionally beat them by 2040.

Today, two buses travel the same stretch of El Camino: a Rapid 522, which makes the full morning commute in about an hour, and a local bus, which takes even longer. But it won't be too long before the already-bad congestion in this growing, car-reliant corridor becomes even worse. Several BRT design alternatives are being explored; in the full build, the line would feature all-door boarding and pre-paid fares, transit priority at traffic signals, train-style stations with real-time information, and one exclusive bus lane in each direction on the six-lane highway.

With some guidance from Chris Lepe at the California transit advocacy TransForm (via Human Transit ), we charted some of the travel time outcomes in various project scenarios (via Appendix F of Appendix H of the massive draft review). What the results show with overwhelming clarity is the importance of giving transit exclusive, car-free travel lanes. With them, El Camino BRT commuters will travel as quickly as drivers; without them, riders have a brutal trip in store.

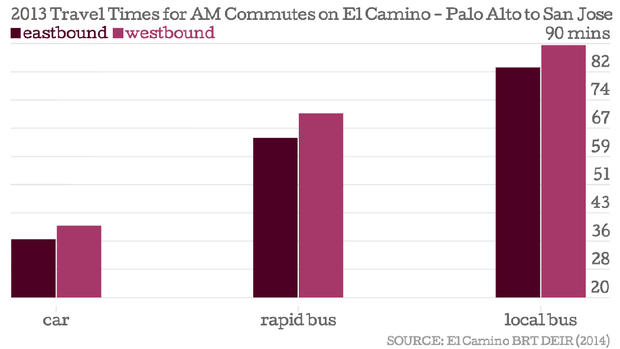

First, let's take a look at the situation as it exists today. Drivers make the full eastbound morning commute in about 36 minutes. Rapid bus riders, meanwhile, take 64 minutes. Local riders fare even worse, at more than 83 minutes from Palo Alto to San Jose. The westbound travel times are a bit longer in each scenario—roughly 40, 71, 90 minutes, respectively—but the car-bus gaps remain equally wide.

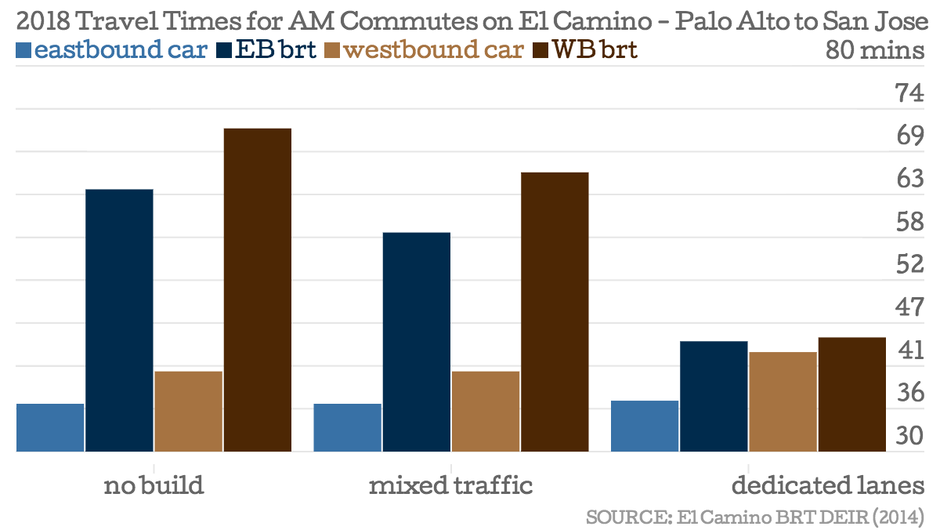

Now let's focus on the three main BRT alternatives. There's the "no build" scenario, which is essentially the Rapid 522 bus as it currently exists. There's a "mixed traffic" scenario, where BRT boarding and station features are implemented but the buses share lanes with cars on El Camino. And there's a "dedicated lane" scenario, where the full BRT gets its own exclusive lane for 14 miles, until it reaches downtown San Jose and merges into regular traffic.

Removing the local bus from consideration, we see the travel-time gap between car and bus steadily shrink as the BRT options improve (below). Heading eastbound in 2018, a rapid bus morning commute would take nearly 30 minutes longer than a drive, and a BRT ride in mixed traffic would take 22 minutes longer. But in a dedicated lane, a BRT commute only takes about 8 minutes longer than driving.

Heading west, the gap shrinks even more. By 2018, only 2 minutes separate a BRT commute in dedicated lanes from a car commute. Taking the bus to work is almost as quick as driving.

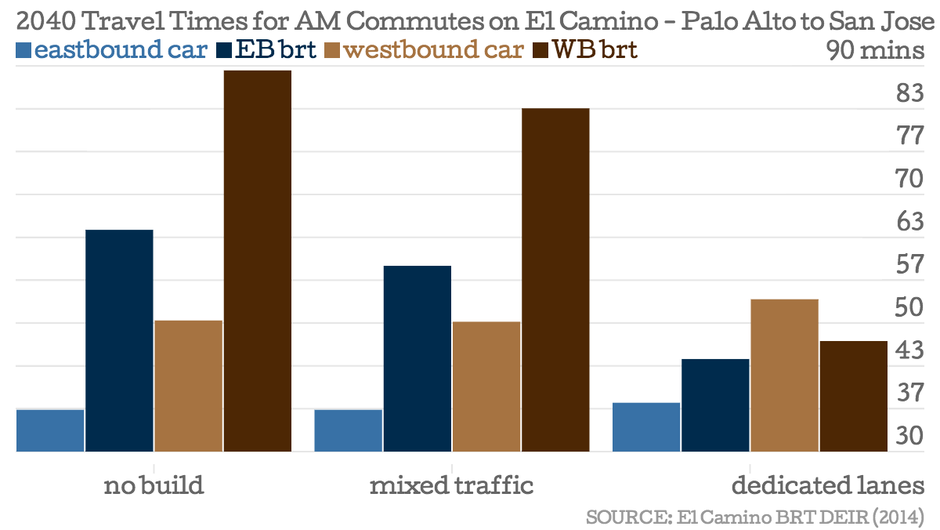

By 2040, the situation heading east during the morning commute is pretty similar across the board (below). A regular rapid bus takes a half hour more than driving, and a mixed-traffic BRT trip still can't compete with a car. But a dedicated BRT commute is only 7 minutes longer than driving.

And look at what happens in the westbound scenario. Travel times in general rise, as a result of regional growth, but a dedicated BRT commute makes the trip in 47 minutes, while a car takes 54 minutes. If that scenario holds, riding the bus becomes a faster commute option than driving to work. In Silicon Valley.

The charts make a couple things clear. Above all, transit that travels in dedicated lanes can compete with driving in terms of commute time and convenience, but transit in mixed lanes can't. Bus travel times in the no-build and mixed-traffic scenarios are rather comparable in the 2018 and 2040 scenarios. In other words, if cities are going to invest in BRT projects at all, they need to give them dedicated travel lanes, or else they're using mountains of taxpayer money for a bus service that isn't much better than what already exists.

(And keep in mind that dedicated BRT would perform even better if the exclusive lanes continued into San Jose, though that's a tougher sell, according to Chris Lepe, because the road there drops from four to six lanes.)

The full-build option of El Camino BRT, with 14 miles of dedicated lanes. ( VTA )

Second, while drivers often complain about losing travel lanes to transit, their commute times barely budge in any of the future scenarios. In 2018, for instance, even with a dedicated BRT lane, the full eastbound commute by car takes only seconds longer than it would today—up to 36.6 minutes from 36.2 minutes—largely because many commuters shift modes. In 2040, a drive alongside dedicated BRT will take only three minutes more than it would have otherwise, hardly an imposition for a project that encourages regional growth. When drivers become satisfied riders, it's a win for all facets of metro area mobility.

The El Camino BRT is far from a done deal. The public must give feedback on the draft environmental review, and since it was evidently prepared using California's old car-friendly traffic standards (which are in the process of being changed to transit-friendly ones ), drivers may still raise a fuss or even threaten litigation. And if the full-build were to win out, the region would need to secure $233 million in capital funding . But projects that help transit compete with driving are exactly the type that should be moving forward—and quickly.

NEXT STORY: The Case Against Universal Preschool