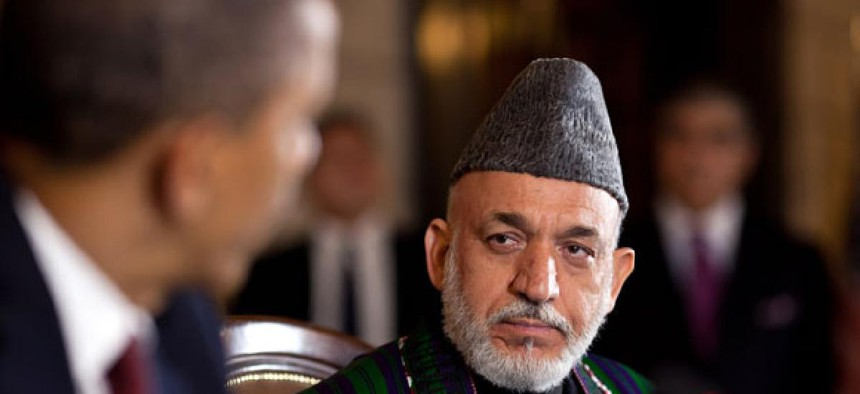

Obama met with Hamid Karzai at the Presidential Palace in Kabul. White House photo

When President Obama and Afghan President Hamid Karzai sit down to lunch at the White House tomorrow, they will attempt to hash out a workable separation agreement. The White House would like to withdraw as many of the remaining 68,000 U.S. troops from Afghanistan as rapidly as possible between now and the end of 2014, and leave as few as necessary behind to continue supporting Afghan Security Forces and striking terrorist targets in the region. Karzai will argue for pledges of maximum U.S. monetary support for years to come, with minimal strings attached that might impinge on Afghan sovereignty and his own room to maneuver domestically. Both leaders will be driven towards hard-bargaining by publics that are bone-weary of the relationship and the conflict at its core.

Casting a pall over the lunch will be the painful example of Iraq. In that case both sides also attempted to negotiate the end to an unpopular war, and the presence of a residual U.S. force to help stabilize the country on its path towards democracy. Instead the talks broke down and U.S. forces withdrew completely at the end of 2011. Iraq has been beset by violence and mired in political stalemate ever since, even as the government in Baghdad has drifted closer towards Iran.

“I can easily see an Iraq-like deadlock in negotiations develop because the United States is already talking troop levels in a residual force of just a few thousand, which is so low as to prove unsupportable, and Karzai wants almost total control and Afghan ownership going forward because he believes both were unduly surrendered during the ’surge’ of U.S. forces,” said Paul Hamill, a former communications adviser to Karzai who is now chief executive officer of the American Security Project. “The danger is that if no agreement is reached for a substantive residual U.S. force, the U.S. Congress is unlikely to keep providing the resources that Afghanistan desperately needs.”

Already, the talks have stumbled over the same issue that tripped-up U.S.-Iraq negotiations: Afghan resistance to granting U.S. forces immunity from prosecution post-2014. After winning concessions from the United States in terms of Afghan authorities assuming control of most Afghan detainees and taking the lead in “night raids,” Karzai has balked at the idea of prosecutorial immunity for U.S. soldiers. Once again, U.S. officials say that is a red line they will not cross.

“As status of forces agreements do around the world where we have U.S. forces stationed on foreign soil, the bilateral security agreement [under discussion with Afghanistan] will establish jurisdictional arrangements to include immunities,” said Douglas Lute, deputy assistant to the president for Afghanistan, told reporters this week. “As we know from our Iraq experience, if there are no authorities granted by the sovereign state, then there is no room for a follow-on U.S. military mission.”

Even if an agreement is reached on a U.S. – Afghan status of forces agreement, there are myriad potential stumbling blocks to a smooth U.S. exit and transition of power in Afghanistan. Some experts believe a minimum U.S. force of up to 30,000 troops would be needed post-2014 to provide nascent Afghan Security Forces with critical enablers such as airlift, logistics, surveillance, command-and-control, medevac and long-range artillery. White House officials reportedly favor troop level options of between 10,000 and 3,000, and have insisted that a “zero option” is also on the table. Afghanistan will also hold critical presidential elections in 2014, in the midst of the NATO pullout. Charges of corruption during the last presidential election in 2009 plunged the country into crisis, and even though Karzai is banned from another term some experts believe he will try and prove kingmaker, with unpredictable results. Without Karzai’s well-established patronage system, it’s unclear that a new president will even be able to extend the federal government’s control beyond Kabul.

“There are both a security and a political transition underway in Afghanistan, and the latter is by far the more dangerous and uncertain,” said former ambassador to Afghanistan James Dobbins, an analyst for the RAND Corporation. “I don’t see the Afghan Army running away in 2014, but the Afghan government could certainly fail as the result of a botched transition.”

For those reasons, Dobbins believes tomorrow’s talks at the White House should be infused with a sense of urgency. “The Obama administration should avoid the situation that developed with Iraq, where we didn’t ask the Iraqis until very late in the process what kind of residual U.S. force they even wanted, which led to the failure of any agreement,” said Dobbins, speaking this week at the Atlantic Council in Washington. “Of course, the obstacle to the current talks is Karzai’s apparent desire to drive the hardest bargain possible, and some of his objectives are both undesirable and unreasonable.”

Hello guys – Perhaps the most agonizing foreign policy issue President Obama has faced is what to do about Afghanistan, the “war of necessity” he ran on in 2008. When he meets with Afghan President Hamid Karzai tomorrow, the discussion will center on the last two outstanding issues still to be decided about the country’s longest-ever war: how fast to withdraw the remaining 68,000 American troops between now and the end of next year, and what, if any, residual U.S. force to leave behind post-2014 to help support Afghan Security Forces and conduct counter-terrorism strikes? The body language of the Obama administration is to get out quick and leave as few troops behind as possible, but both decisions would add risk to an enterprise already stretching the limits of its margins of error.

NEXT STORY: Zero Dark Thirty is about more than torture