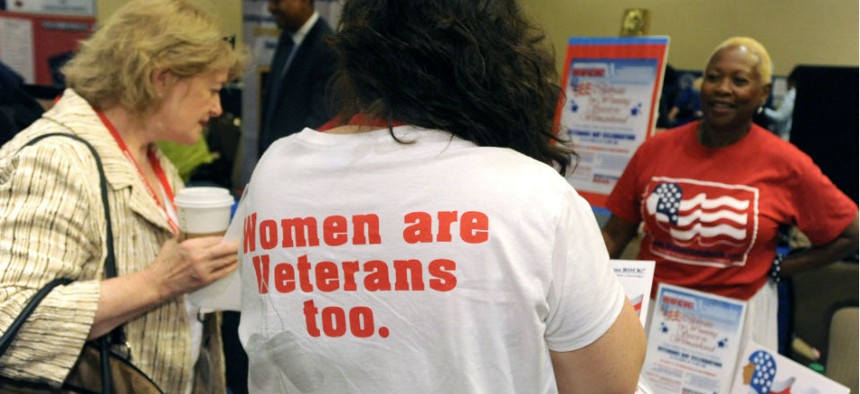

Women attend a veterans training summit in Washington. Robert Turtil/VA file photo

Does the VA Have a Women Veterans Problem?

Both inside and outside of the department, there's one consensus: More work needs to be done.

When Angela King left the Navy and enrolled in Ohio State University, she struggled to find classmates who could understand her military experience.

But instead of turning to a local branch of the Veterans Affairs Department for support, she looked for help in a student veterans group on campus.

"I think a lot of women feel like they don't fit in [at the VA]. I think there's not a lot of trust in the community to receive care there," said King, 28, who is now a graduate student at Duke University School of Medicine in North Carolina.

And it's not just King. Officials and advocates agree: The department has a long way to go in its handling of the many issues faced by women veterans.

In many ways, female veterans face tougher challenges than their male counterparts, as they are more likely to be uninsured, unemployed, divorced, and suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder—often the result of a sexual assault.

"They were in theater, they were in very different traumatic types of environment. And they're coming back to a VA that is built more for male veterans," said Garry Augustine, the executive director for Disabled American Veterans, a Washington-based advocacy organization.

As advocates like to point out, gaps in care reach the most basic levels. For example, about one-third of VA clinics don't even have a gynecologist on staff, requiring them to send their female veterans elsewhere.

At the same time, the number of female veterans is on the rise. By 2043, the VA projects that the number of female veterans will increase by 16 percent, while the number of male veterans will decrease by almost 40 percent.

But women are still an overwhelmingly small part of the veteran population. In 2014, women accounted for almost 10 percent of the total veterans population, or 2 million veterans out of a total U.S. population of nearly 22 million. And females account for more than 18 percent of veterans who enlisted after Sept. 11, 2001.

This minority status of women veterans is largely to blame for the gender gap in coverage at the VA, according to a Disabled American Veterans report released late last month. It notes that discrepancies in treatment of women at the VA "result from a disregard for the differing needs of women veterans and focusing on the 80-percent solution for men."

Women make up roughly 7 percent of the veterans using VA health care, according to department data. With such a small population, service members stressed the importance of creating more female-centric care at the VA, including establishing health centers specifically for women veterans.

"I wouldn't have gone to the VA if they didn't have that women's clinic," said Jill Finken, a member of the Army National Guard in Iowa. "... I kind of felt embarrassed, because it's a bunch of men who served in WWII and Vietnam.… Having the women's clinic was a place where I didn't feel like such a fraud."

The VA has made progress in recent years, including a requirement that every medical center have a women veterans program manager who helps coordinate female care. But top officials acknowledge that hurdles remain.

"I will tell you that post their separation from service, [women] have a fundamentally different experience," said Allison Hickey, the VA's undersecretary for benefits, at a Council on Foreign Relations event in New York last week.

And for department staffers, the challenge begins with trying to get women to sign up for VA services. Some service members won't self-identify as a veteran after they leave the military, meaning they opt out of receiving VA benefits—including health care, education, disability, and employment assistance. And most veterans who don't self-identity are female.

"The tendency as a woman veteran is ... when you hang up the uniform, you are disconnected with your colleagues in service.... I mean, the lines are cut. There is no—very little connection," Hickey said. "... They seem to fall off into invisible environments. And so we have to do some things very strategically to grab them and pull them back in."

But a VA spokesperson said that because they don't come forward as veterans, it's impossible for the department to know, or even estimate, how many are choosing to opt out.

Service members said that females choosing not to self-identity as veterans reflects long-standing issues of gender inequality within the military, where many combat-heavy, infantry jobs are all but closed off to women.

"There has to be a change to some degree within the service component.... The reality is that the infantry is the ... crown jewel of the military," said Finken, 36, adding that this leaves some women with a "second-class citizen feeling."

This can be compounded by societal pressures. Women go from the military—where traditional feminine characteristics are discouraged—to a very different civilian world.

"All of the sudden you're supposed to be this caring, loving, folding-laundry person," Finken said. "... That is going to be difficult. It's because of society's expectations of females."

But advocates are hopeful that the VA is dedicated to improving services for female veterans.

"I think in general the VA is making strides to change the culture that has caused the problems," Augustine said. But he said Disabled American Veterans doesn't have a specific timeline for wanting to see specific changes within the organization.

"What we would like to see is progress," he said. "... It's like turning a battleship when you try to change a bureaucracy."

NEXT STORY: A Glossary of Ebola Contact Types