John Kirby, the Pentagon press secretary, outlines part of the strategy against ISIS in September. Glenn Fawcett/Defense Department

$300,000 an Hour: The Cost of Fighting ISIS

What price will the U.S. ultimately pay to neutralize the Islamic State?

It's been 96 days since the United States launched its first airstrikes against ISIS militants in Iraq; 50 since it expanded that campaign into Syria. And on each one of those days, the U.S. government has spent an average of roughly $8 million, or more than $300,000 an hour, on the operation against the Sunni Muslim extremist group, according to Pentagon officials .

That's a trivial sum compared with the more than $200 million the U.S. pours each day into its 13-year war in Afghanistan (the National Priorities Project , which advocates for budget transparency, estimates that the U.S. has now spent more than $1.5 trillion on its wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and against ISIS, since 2001). But the bean-counting matters, because the place values and line items offer clues to understanding the military offensive President Obama has committed the country to—and now asked Congress to bless .

On Tuesday, for instance, Defense News reported that most of the $5.6 billion in additional funding that Obama recently requested from Congress to fight ISIS will go toward training and equipping the Iraqi and Kurdish militaries, operating military aircraft over Syria and Iraq, and transporting troops and materiel through the region (last week, the White House doubled the number of American soldiers deployed to Iraq in an advisory role, authorizing as many as 3,100 troops). The administration, in other words, is betting billions on a military operation largely predicated on 1) pounding the Islamic State by air and 2) beefing up local forces that can challenge the group on the ground.

The budget for the operation also highlights the ambiguity surrounding when exactly America's campaign against ISIS began. During a press conference in late August, Rear Admiral John Kirby, the Pentagon press secretary, suggested that U.S. military engagement commenced on June 16, when Obama sent 275 troops to defend the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad. But according to Defense News , the Defense Department has since changed course, arguing that the operation in fact began on August 8, the day airstrikes started in Iraq. The Pentagon has not disclosed the price tag for U.S. military activity between June 16 and August 8, though Defense News estimates the cost during that period at around $400 million. All told, that would mean the U.S. has so far spent more than $1 billion on its campaign against ISIS.

Most importantly, the numbers serve as a guide not only to when this all began, but also to how it ends. In September, Obama pledged to " degrade and ultimately destroy " ISIS. Thus far, the president's campaign appears to be doing more degrading than destroying. Last week, The New York Times reported that the U.S.-led coalition and various forces on the ground have helped halt the Islamic State's rapid advance in Iraq and Syria, and even reversed some of the group's territorial gains in Iraq. Airstrikes have also forced the jihadists to ditch their military bases for civilian homes (and their flashy convoys for more discreet means of transportation), while depleting ISIS revenues by taking out oil wells and refineries controlled by the group. (Airstrikes aside, ISIS may also simply have alienated local populations and run out of marginalized, sympathetic, Sunni-majority areas to conquer.)

But nearly 800 airstrikes into the U.S.-led military operation, ISIS still controls sizable pockets of territory in Syria and Iraq (the shaded areas in the map below). Strikes have targeted the Islamic State's leaders and rank-and-file, but foreigners continue to join the group in large numbers, and its fighting force remains formidable.

Top U.S. officials acknowledge that airstrikes can only do so much to counter the Islamic State. "The airstrikes are buying us time," General Ray Odierno, the Army chief of staff, told CNN in late October. It will take several years to "significantly degrade" ISIS, he said, and doing so will depend in great measure on the efforts of local ground forces such as the Iraqi army and Kurdish peshmerga. (The U.S. appears to be more concerned with dislodging ISIS in Iraq than in Syria, where it is focusing instead on neutralizing the group's command centers and revenue sources, and reportedly training Syrian opposition fighters to defend rather than seize territory.)

"Over time, if that's not working, then we're going to have to reassess and we'll have to decide whether we think it's worth putting other forces in there, to include U.S. forces," Odierno added.

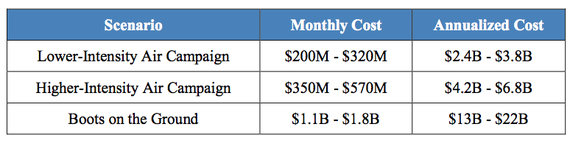

That's a multibillion-dollar "if." In September, the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) estimated the annual costs of America's campaign against ISIS based on three scenarios of how it will evolve: 1) a low-intensity air campaign; 2) a high-intensity air campaign; and 3) a deployment of 25,000 U.S. combat forces to the region.

Obama has ruled out dispatching U.S. ground troops to fight ISIS, but wars—even limited ones—unfold in unpredictable ways. As the authors of the CSBA's report write:

The cost estimates presented here highlight the high degree of uncertainty involved in current operations. One source of uncertainty are the desired end states in both Iraq and Syria—i.e., what the United States would like to leave in place if and when ISIL is destroyed. Another source of uncertainty is what will be required of the United States to achieve its desired end state and how long it will take. The former is a matter of strategy while the latter is a matter of tactics and planning—and the enemy has a say in both.

As the U.S. air campaign continues, and as ISIS fighters melt into their surroundings, the number of targets will likely dwindle even as the enemy remains, weakened but undefeated. What then? How will Obama define the mission to "ultimately destroy" ISIS? Follow the money.