necladrup / Shutterstock.com

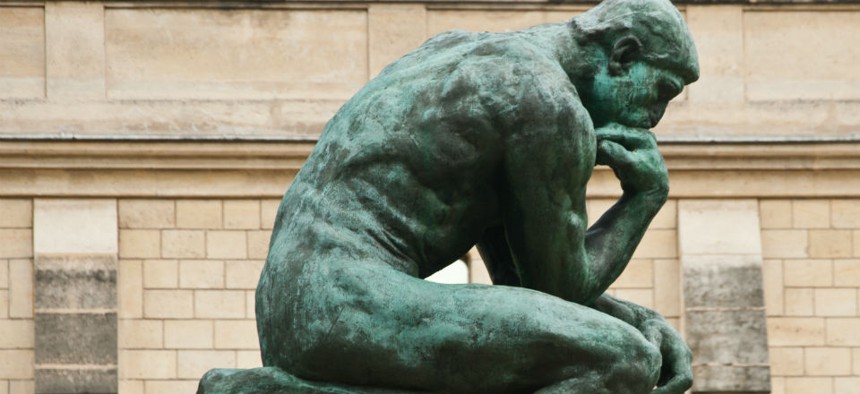

Why Air Force Cadets Need to Study Philosophy

Greater emphasis on humanities means more well-rounded decision making.

Ten years ago as a member of the U.S. Air Force, Jim Solti was charged with briefing a three-star admiral with some technical analyses that were “going to be a difference-maker in the height of the Iraq war.” He and his team had spent a month analyzing data about the relationships of infrastructural networks, like the electric grid and railroads, to derive the best recommendation for future military actions that would have the fewest secondary consequences as possible. But when showtime finally came and the team presented its findings, the admiral dismissed them very quickly.

"Our initial reaction was that this older guy doesn’t get the power of what we presented, said Solti, now the chief scientist at the U.S. Air Force Academy. But he quickly realized that the admiral not only understood what the team had told him, but that he had also already worked this new information into the larger picture of the task at hand. The admiral, who had a background in international relations, knew that whatever plan of action he took would affect the local community, and making that decision without the appropriate context of the region’s history and culture could mean much graver consequences for civilians and the military. Data alone didn’t suffice. “I think that’s what the humanities and social sciences provide: the ability to take those ones and zeroes and put them in the broader context,” Solti said.

That was an epiphany for Solti. He realized that his training in computational structural mechanics wasn't enough. "I was an active-duty airman for 15 years before realizing my gut was as valuable as my mind; my intuition as useful as scientific analyses; and my agility, creativity and innovation honed the decision-making necessary to function in complex environments, Solti wrote in a recent blog post. Now he advises those who design the curriculum at the U.S. Air Force Academy, and he’s finding new ways to give students the technical education they need to be airmen while broadening their scope and imparting them with the more holistic worldview afforded by the liberal arts. That involves honing students’ critical-thinking skills, for example, or encouraging them to analyze the historical legacies of present-day challenges.

From repairing planes to encrypting classified information, people who work in the Air Force need a background in science, technology, engineering, and math—fields collectively known as STEM. But the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs is an officer-training school with a liberal arts bent. “The courses that our students take are weighted heavily in STEM fields, but cadets are exposed to a holistic curriculum,” Solti said. For example, cadets are required to complete a capstone at the end of their education so that they can integrate the various subjects they have learned over the past four years.

Solti and others at the Academy see a background in the humanities as a way to understand complex, interdisciplinary relationships between seemingly disparate entities. When military decision-makers consider possible tactics to approach a situation, they have to consider the people and relationships that decision may affect, even if those results aren’t immediately obvious. "It’s not just taking down the electric power, for example, it’s about the effect [that action] creates, Solti said. "Electricity powers computers that feed the financial network that feeds [the] economy—it’s a single integrated system. And to evaluate how people in a country might react to an action like that, historical and cultural reference points can make the difference between a successful operation and a debacle.

For airmen, this holistic understanding is most important in time-sensitive situations when they have to make high-stakes decisions. So administrators have built these hypothetical decision-making opportunities into the curriculum. "One great example is that we allow our cadets to operate a war room-type scenario where they are conducting a mission, Solti said. "They have to make these real decisions in a safe virtual environment. But you can see some of these ‘aha’ moments when they’re making what turn out to be poor decisions constrained by uncertainty and time. These wrong decisions are the "scar tissue that students develop and that informs their decision-making when the stakes are higher.

Exercises like the war room work best when they are interdisciplinary by design, a microcosm of the real world. "We partner engineers with legal majors and history majors and management majors, Solti said. "They form holistic teams that are able to tackle any problem, so they gain appreciation for their peers and for the power of the curriculum they’re learning.

For non-military schools, Solti noted that events like robotics competitions and debates create similar opportunities for interdisciplinary learning and appreciation. "The more experience [educators] give students that don’t have canned solutions, that have time constraints, that really test their ability and their gray matter, the better their minds’ ability to synthesize what they’ve learned, Solti said.

But educators at the Academy have to consider the real-world applications of their lessons, so they stress that the greater focus on the humanities doesn’t mean a decreased emphasis on STEM. "It’s not a trade off, it’s not a zero-sum game where engineers gain and humanities lose, Solti said. With more cross-disciplinary projects, Solti hopes that Air Force students from all fields can work together toward a common goal. Eventually, when those students are in the field and under pressure, they can remember all the nuances at play and make the right decision.

(Image via necladrup / Shutterstock.com)