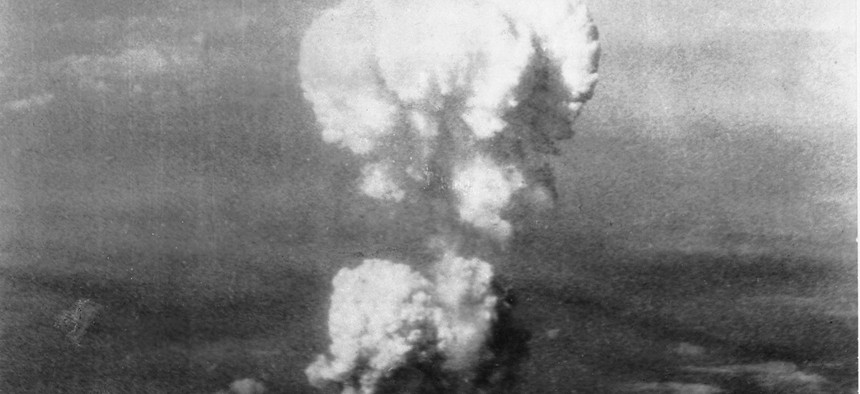

The mushroom cloud over Hiroshima after the bombing was visible for miles. Sgt. George R. Caron/ United States Air Force file photo via National Archives

The Federal Employees Who Singled Out Hiroshima for Atomic Destruction

How committee meetings, memos, and largely arbitrary decisions ushered in the nuclear age.

On May 10, 1945, three days after Germany had surrendered to the Allied powers and ended World War II in Europe, a carefully selected group of scientists and military personnel met in an office in Los Alamos, New Mexico. With Germany out of the war, the top minds within the Manhattan Project, the American effort to design an atomic bomb, focused on the choices of targets within Japan. The group was loosely known as the Target Committee, and the question they sought to answer essentially was this: Which of the preserved Japanese cities would best demonstrate the destructive power of the atomic bomb?

General Leslie Groves, the Army engineer in charge of the Manhattan Project, had been ruminating on targets since late 1944; at a preliminary meeting two weeks earlier, he had laid down his criteria. The target should: possess sentimental value to the Japanese so its destruction would “adversely affect” the will of the people to continue the war; have some military significance—munitions factories, troop concentrations, and so on; be mostly intact, to demonstrate the awesome destructive power of an atomic bomb; and be big enough for a weapon of the atomic bomb’s magnitude.

Groves asked the scientists and military personnel to debate the details: They analyzed weather conditions, timing, use of radar or visual sights, and priority cities. Hiroshima, they noted, was “the largest untouched target” and remained off Air Force General Curtis LeMay’s list of cities open to incendiary attack. “It should be given consideration,” they concluded. Tokyo, Yawata, and Yokohama were thought unsuitable—Tokyo was “all bombed and burned out,” with “only the palace grounds still standing.”

A fortnight later, at the formal May 10 target meeting, Robert Oppenheimer, the chief scientist on the project, ran through the agenda. It included “height of detonation,” “gadget [bomb] jettisoning and landing,” “status of targets,” “psychological factors in target selection,” “radiological effects,” and so on. Joyce C. Stearns, a scientist representing the Air Force, named the four shortlisted targets in order of preference: Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Kokura. They were all “large urban areas of more than three miles in diameter;” “capable of being effectively damaged by the blast;” and “likely to be unattacked by next August.” Someone raised the possibility of bombing the emperor’s palace in Tokyo—a spectacular idea, they agreed, but militarily impractical. In any case, Tokyo had been struck from the list because it was already “rubble,” the minutes noted.

Kyoto, a large industrial city with a population of 1 million, met most of the committee’s criteria. Thousands of Japanese people and industries had moved there to escape destruction elsewhere; furthermore, stated Stearns, Kyoto’s psychological advantage as a cultural and “intellectual center” made the residents “more likely to appreciate the significance of such a weapon as the gadget.”

Hiroshima, a city of 318,000, held similar appeal. It was “an important army depot and port of embarkation,” said Stearns, situated in the middle of an urban area “of such a size that a large part of the city could be extensively damaged.” Hiroshima, the biggest of the “unattacked” targets, was surrounded by hills that were “likely to produce a focusing effect which would considerably increase the blast damage.” On top of this, the Ota River made it “not a good” incendiary target, raising the likelihood of its preservation for the atomic bomb.

The meeting barely touched on the two cities’ military attributes, if any. Kyoto, Japan’s ancient capital, had no significant military installations; however, its beautiful wooden shrines and temples recommended it, Groves had earlier said (he was not at the May 10 meeting), as both sentimental and highly combustible. Hiroshima’s port and main industrial and military districts were located outside the urban regions, to the southeast of the city.

The gentlemen unanimously agreed that the bomb should be dropped on a large urban center, the psychological impact of which should be “spectacular” to ensure “international recognition” of the new weapon.

* * *

The Target Committee regrouped at the Pentagon on May 28 (Oppenheimer sent a representative). The members concentrated on the aiming points within the targeted cities. The plane carrying the atomic bomb “should avoid trying to pinpoint” military or industrial installations because they were “small, spread on fringes of city and quite dispersed.” Instead, aircrews should “endeavor to place … [the] gadget in [the] center of selected city.” They were quite explicit about this: The plane should target the heart of a major city. One reason was that the aircraft had to release the bomb from a great height—some 30,000 feet—to escape the shock wave and avoid the radioactive cloud; that limited the target to large urban areas easily visible from the air.

Captain William “Deak” Parsons, associate director of Los Alamos’s Ordnance Division, gave another reason to drop the bomb on a city center: “The human and material destruction would be obvious.” An intact urban area would show off the bomb to great effect. Whether the bomb hit soldiers, ordnance, and munitions factories, while desirable from a publicity point of view, was incidental to this line of thinking—and did not influence the final decision. “No one on the Target Committee ever recommended any other kind of target,” McGeorge Bundy, a Washington insider who later became John F. Kennedy’s national security advisor, later wrote, “and while every city proposed had quite traditional military objectives inside it, the true object of attack was the city itself.”

The Target Committee dismissed talk of giving a prior warning or demonstration of the bomb to Japan. Parsons had persistently rejected suggestions of a noncombat demonstration: “The reaction of observers to a desert shot would be one of intense disappointment,” he had warned in September 1944. Even the crater would be “unimpressive,” he said. Groves shared his contempt for “tender souls” who advocated a noncombat demonstration. When the meeting ended, the committee had no doubt about where the first atomic bomb would fall: on the heads of hundreds of thousands of civilians.

During June, the Target Committee narrowed the choice. On the 15th, a memo elaborated on Kyoto’s attributes. It was a “typical Jap city” with a “very high proportion of wood in the heavily built-up residential districts.” There were few fire-resistant structures. It contained universities, colleges, and “areas of culture,” as well as factories and war plants, which were in fact small and scattered, and in 1945 of negligible use. Nevertheless, the committee placed Kyoto higher on the updated “reserved” list of targets (that is, those preserved from LeMay’s firebombing). Kokura, too, made the reserved list. That city possessed one of Japan’s biggest arsenals, replete with military vehicles, ordnance, heavy naval guns, and, reportedly, poison gas. It was the most obvious military target.

* * *

Another high-powered group ran in parallel with the Target Committee: the Interim Committee of top officials convened by Secretary of War Henry Stimson to advise the president on the future of nuclear power for military and civilian use. On paper, the Interim Committee looked omnipotent. Its permanent members included Stimson; James Byrnes, the president’s “personal representative” pending his appointment as secretary of state; and various other top military and civilian officials. The scientists Oppenheimer, Arthur Compton, Ernest Lawrence, and Enrico Fermi sat on the committee’s scientific panel. General George Marshall, Army chief of staff, and Leslie Groves received open invitations to attend meetings.

In practice, the committee’s influence ebbed away. The problem was Stimson. The war secretary anchored his authority to the committee’s success and personally invited the members. Some turned up as a courtesy, but attendance levels swiftly declined. Groves attended once. The immediate demands of the atomic mission preoccupied him; he had little time for Stimson’s visionary talk about the future of atomic power. There was a war to be won.

At 10 a.m. on May 31, the committee members filed into the dark-paneled conference room of the War Department. The air was heavy with the presence of three Nobel laureates and Oppenheimer. Stimson opened the proceedings on a portentous note: “We do not regard it as a new weapon merely,” he said, “but as a revolutionary change in the relations of man to the universe.” The atomic bomb might mean the “doom of civilization,” or a “Frankenstein” that might “eat us up”; or it might secure world peace. The bomb’s implications “went far beyond the needs of the present war,” Stimson said. It must be controlled and nurtured in the service of peace.

Oppenheimer was invited to review the explosive potential of the bombs. Two were being developed: the plutonium bomb and the fissile uranium bomb. They used different detonation methods and processes, yet both were expected to deliver payloads ranging from 2,000 to 20,000 tons of TNT. Nobody yet knew their precise power. More advanced weapons might measure up to 100,000 tons; and superbombs—thermonuclear weapons—10 million to 100 million tons, Oppenheimer said. The scientists nodded impassively; they were inured to such fantastic figures.

However, the numbers and the destruction they implied “thoroughly frightened” incoming Secretary of State Byrnes, as he later admitted. He was human, after all; but beyond his horror at the statistics, he silently ruminated on the wisdom, or madness, of any talk of sharing the secret with Moscow. As such, Byrnes the politician resolved to pursue his “go it alone” policy for America that would pointedly exclude the Russians and indeed the rest of the world from the atomic secret: The bomb’s power would be the future source of American power. Discussion flared on the question of whether to share the secret with Russia (by which point Stimson had left for another meeting). Oppenheimer advocated divulging the secret “in the most general terms.” Moscow had “always been very friendly to science,” he rather lamely observed; he felt strongly, however, that “we should not prejudge the Russian attitude.” Marshall wondered, too, whether a combination of likeminded powers might control nuclear power; the general even suggested that Russian scientists be invited to witness the bomb test at Alamogordo, scheduled for July.

Such talk alarmed Byrnes, who had observed the Russians at close quarters at Yalta, and Groves, who was violently opposed to sharing with Moscow a secret he had spent almost four years trying to keep. Byrnes swooped: If “we” were to give information to the Russians “even in general terms,” he argued, Stalin would demand a partnership role and a stake in the technology. Indeed, not even the British possessed blueprints of America’s atomic factories.

Byrnes then wrapped up the argument: America should “push ahead as fast as possible in [nuclear] production and research to make certain that we stay ahead and at the same time make every effort to better our political relations with Russia.” All agreed. If anyone noticed this first official recognition of the start of a nuclear-arms race—not with Germany or Japan, but with Russia—he did not say so.

After lunch, the meeting’s participants (minus Marshall) examined the next point on the agenda: “the effect of the bombing of the Japanese and their will to fight.” Would the nuclear impact differ much from an incendiary raid? one member of the committee wondered. That rather missed the point, objected Oppenheimer, stung by the suggestion that mere firebombs were in any way comparable: “The visual effect of the atomic bomb would be tremendous. It would be accompanied by a brilliant luminescence which would rise to a height of 10,000 to 20,000 feet. The neutron effect of the explosion would be dangerous to life for a radius of at least two-thirds of a mile.” The same could not be said of LeMay’s jellied petroleum raids. “Twenty thousand people,” Oppenheimer estimated, would probably die in the attack.

Stimson, meanwhile, was personally preoccupied with saving Kyoto, the ancient capital whose temples and shrines he had visited with his wife in 1926. He requested that it be struck from the shortlist of targets. Japan was not just a place on a map, or a nation that must be defeated, he insisted. The objective, surely, was military damage, not civilian lives. In Stimson’s mind the bomb should “be used as a weapon of war in the manner prescribed by the laws of war” and “dropped on a military target.” Stimson argued that Kyoto “must not be bombed. It lies in the form of a cup and thus would be exceptionally vulnerable. … It is exclusively a place of homes and art and shrines.”

With the exception of Stimson on Kyoto—which was essentially an aesthetic objection—not one of the committee men raised the ethical, moral, or religious case against the use of an atomic bomb without warning on an undefended city. The businesslike tone, the strict adherence to form, the cool pragmatism, did not admit humanitarian arguments, however vibrantly they lived in the minds and diaries of several of the men present.

Total war had debased everyone involved. While older men, such as Marshall and Stimson, shared a fading nostalgia for a bygone age of moral clarity, when soldiers fought soldiers in open combat and spared civilians, they now faced “a newer [morality] that stressed virtually total war,” observed the historian Barton J. Bernstein. In truth, the American Civil War and the Great War gave the lie to that “older morality,” as both men knew. Marshall recommended, for example, on May 29, in discussion with Assistant War Secretary John McCloy, the use of gas to destroy Japanese units on outlying Pacific islands: “Just drench them and sicken them so that the fight would be taken out of them—saturate an area, possibly with mustard, and just stand off.” He meant to limit American casualties with whatever means available.

If he drew on outdated civilized values, Stimson grasped the moral implications of nuclear war. The idea of the bomb tormented him—so much that he sought comfort in the notion of recruiting a religious evangelist to “appeal to the souls of mankind and bring about a spiritual revival of Christian principles.” America, he believed, was losing its moral compass just as it might be about to claim military supremacy over the world. The dawn of the atomic era called for a deeper human response, he believed, energized by a spirit of cooperation and compassion. He did not act on his compulsion, but dwelt long on the atomic question—and the question in Stimson’s troubled mind was not “Will this weapon kill civilians?” but rather, if we continue on this course, “Will any civilians remain?” He poured much of his anxiety into his diary.

Officially, Stimson seemed contradictory and muddled. In the meetings, he summarized his position on the bomb thus: (1) “We could not give the Japanese any warning;” (2) “We could not concentrate on a civilian area;” (3) “We should seek to make a profound psychological impression on as many of the inhabitants as possible.” He meant to use the bomb to shock the enemy—“to make a profound impression”—with a display of devastation so horrible that Tokyo would be forced to surrender. However, he insisted it must be a military target. His statement’s inherent contradiction—how could the bomb shock Tokyo without concentrating on a civilian area?—either eluded Stimson, or he lacked the intellectual honesty to confront it. Whatever the case, it provoked no comment in the Interim Committee meeting, and eased the task of James Conant, a prominent scientist on the committee: “The most desirable target,” then, he said, “would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses.”

Stimson persuaded himself that this meant a military target. The physicists on the committee’s scientific panel agreed; Groves ticked off another victory; and the war secretary’s self-deception was complete. A slightly surreal atmosphere lingered, as the men reflected on what they had done. The meeting that had opened with Stimson’s declaration of mankind’s “new relationship with the universe” ended with his approval of the first atomic attack, on the center of a city, to which he consented moments after he had rejected the bombing of civilians.

The committee unanimously agreed that the atomic bombs should be used: (1) as soon as possible; (2) without warning; and (3) on war plants surrounded by workers’ homes or other buildings susceptible to damage, in order to make a spectacular impression “on as many inhabitants as possible.”

* * *

On June 1, 1945, President Harry Truman rose early to prepare a statement for Congress. It was a bright summer’s day, and he chose one of his three new seersucker suits—a gift from a New Orleans cotton company. The president felt refreshed after hosting the prince regent of Iraq at a state dinner a few nights earlier. He had spent Memorial Day on the presidential yacht, cruising the Potomac, playing poker, and approving his speech for the San Francisco Conference on the creation of the United Nations, then in session.

That June morning, Truman received Byrnes’s summary of the previous day’s marathon Interim Committee meeting. Byrnes had skillfully exploited his position as the president’s special representative, laying stress where he saw fit, emphasizing the consensus on the weapon’s use and, in effect, relegating Stimson to the sidelines. Byrnes’s upbeat assessment fortified the president for his important speech.

“There can be no peace in the world,” Truman told a rapt house, “until the military power of Japan is destroyed. ... If the Japanese insist on continuing resistance beyond the point of reason, their country will suffer the same destruction as Germany.”

But the fate of individual cities was still being decided. That month, Stimson asked Groves—then in his office on a different matter—whether the target list had been finalized, and was disturbed to see Kyoto at the top of the list. Again, he ordered it struck off. Groves fudged. They irked him, these meddlesome politicians: The destruction of Kyoto was his to decide; he felt a sense of proprietorial control over how the bomb should be used. The city “was large enough an area for us to gain complete knowledge of the effects of the atomic bomb. Hiroshima was not nearly so satisfactory in this respect.” For weeks, Groves continued to refer to Kyoto as a target despite Stimson’s clear instructions to the contrary. Then, on June 30, Groves very reluctantly informed the Chiefs of Staff that Kyoto had been eliminated as a possible target for the atomic fission bomb and all bombing, by direction of the secretary of war.

That left four cities on the target list: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki, listed in order of how well they conformed to the Target Committee’s criteria. Nagasaki, being hilly, was not ideal, but its Mitsubishi Shipyards (then out of use), where Japan’s huge battleships had been built, gave it strong symbolic appeal.

On July 25, 1945, Groves finalized these targets in a directive issued for Carl Spaatz, the commanding general of the United States Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific: “The 509 Composite Group, 20th Air Force will deliver its first special bomb as soon as weather will permit visual bombing after about 3 August 1945 on one of the targets. … Additional bombs will be delivered on the above targets as soon as made ready.”

A clear-weather report for August 6 made Hiroshima the preferred target on the list that day. Seventy years ago, the first atomic bomb fell on the city.

This article has been adapted from Paul Ham's book Hiroshima Nagasaki: The Real Story of the Atomic Bombings and Their Aftermath.