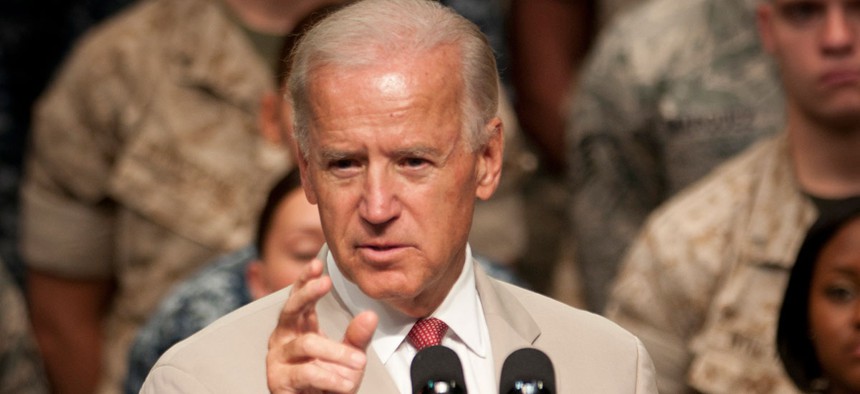

Airman 1st Class Krystal Garrett/Air Force file photo

Joe Biden is now the vice president who will not be president. He’s been VP for seven and a half years, preceded by decades of work on U.S. foreign policy in the Senate, but the question remains whether he is distinctive in any memorable way for his work in international affairs. Was he simply a glad-handing flack pushing the Obama agenda, a manic schmoozer of foreign leaders? A gaffe-prone foreign-policy dilettante who, in the long run, won’t matter?

Biden puts some people off. His critics argue that despite his passion for worthy causes—from efforts to stabilize Iraq to the “cancer moonshot” to his task force devoted to “a strong middle class”—his bouts of imprecision and occasional foot-in-mouth foibles get in the way. An adviser to retired General Stanley McChrystal reportedly referred to Biden as “Bite Me.” Former Defense Secretary Bob Gates wrote in his memoir, Duty, that Biden has been “wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades.”

That hasn’t been my observation. I have traveled with Biden during his vice presidential tenure to Asia and Europe, watched him interact with foreign leaders abroad and at home, and have had wide-ranging discussions with him since his Senate days on everything from the confirmation battle over John Bolton’s nomination as U.N. ambassador to how the U.S. should approach its challenges in Iraq and Afghanistan. I haven’t always agreed with Biden’s positions, but those positions have tended to follow a pattern and demonstrate a consistency of approach, analysis, and engagement that stands out—particularly when compared to many other foreign-policy players who often don’t leave clear footprints.

The Biden Doctrine, as I’ve seen it emerge and as he described it to me in a recent interview in his White House office, contains some familiar elements. He can sound like a realist in the mold of George H.W. Bush’s national security advisor Brent Scowcroft—decisions on whether to deploy America’s “enormous military capability,” he said in the interview, should depend on assessments of “(a) what is the strategic interest? And (b) what are the second, third, and fourth steps in this process?” His contention to me that “you do not commit force unless you can demonstrate that the use of that force is sustainable and will produce an outcome” sounds nearly identical to the views President Barack Obama expressed to Jeffrey Goldberg in The Atlantic article “The Obama Doctrine.” So does his insistence that the U.S. has to “engage because the world has changed,” but that this has to involve “sharing responsibility, sharing intelligence, and allocating force on targets so we’re not the only game in town.”

Yet what makes his approach distinctive is that he may very well be the nation’s first “personality realist.” Unlike Obama—whose relationships with world leaders from Japan’s Shinzo Abe to Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu are famously chilly—Biden says of his doctrine that “it all gets down to the conduct of foreign policy being personal. ... All [foreign policy] is, is a logical extension of personal relationships, with a lot less information to act on.”

It’s not as easy to discern as clear a framework for decisionmaking from the former secretary of state, and current Democratic presidential nominee, Hillary Clinton. She may well have a doctrine, but what we know so far of her broad choices in foreign policy don’t yet add up to a set of replicable practices. As secretary of state, for example, Clinton pushed “digital diplomacy” and the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review, a kind of counterpart to the military’s own quadrennial review, this one aimed at evaluating the civilian elements of foreign policy. She pushed women’s rights, global poverty fixes, and economic development as strategic interests—but it’s not clear she consolidated these as American foreign-policy priorities during her time in the Obama administration.

As for national security, some, including this writer, have criticized Clinton for having her clutch stuck on “intervention,” and indeed this does appear to be the key pattern in Clinton’s approach. She supported the U.S. surge of forces into Afghanistan in 2009, at a time when Biden opposed it. In 2011, she supported both America’s Libya intervention and the raid to kill Osama bin Laden. But there are standout moments at odds with this tendency—such as buying into negotiations with Iran and cautioning against pushing Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak out of office too abruptly in 2011—where she favored restraint.

In contrast, Biden’s approach has been definitive enough, particularly in approaching leaders, to hold clear lessons for future foreign-policy practitioners—including presidents such as, possibly, Hillary Clinton herself.

When I asked Biden recently to define for me what he thought the “Biden Doctrine” was, he opened in a Bidenesque way: “My dad used to say to me, ‘Champ, if everything is equally important to you, nothing is important to you.’ So the hardest thing to do, I’ve found in 44 years, is to prioritize what really are the most consequential threats and concerns, and allocate resources relative to the nature of the threat.” Americans, he said, tend to over-respond to the “wolf at the door” without recognizing that there are other wolves out in the field.

The “wolves in the field,” then—the real existential threats facing the nation—he sees not as terrorism, even from ISIS, but rather the prospect of “loose nukes, and unintended nuclear conflict that erupts with another nuclear power” like Russia or China. Other big threats include “that not-stable figure in North Korea,” Kim Jong Un, and Pakistan, which, he reminded me, he dubbed the “most dangerous nation in the world” nine years ago.

“Terrorism is a real threat,” Biden said, “but it’s not an existential threat to the existence of the democratic country of the United States of America. Terrorism can cause real problems. It can undermine confidence. It can kill relatively large numbers of people. But terrorism is not an existential threat.” If Biden were running for the presidency, this piece of the Biden Doctrine—what he calls “proportionality”—would no doubt be red meat for many who place terrorism at the heart of America’s challenges today.

The other striking element of the Biden doctrine is the degree to which it depends on establishing personal relationships. I had seen Biden take his granddaughter Finnegan to China to help break open new terrain with the new Chinese leader when Xi Jinping first took office, and do the same with his granddaughter Nicole in meetings last January with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He told me in the interview that in conducting foreign policy, “You’ve got to figure out what is the other guy’s [leader’s] bandwidth. ... You have to figure out what is realistically possible ... so that you can begin to make more informed judgments about what they are likely to do or what you can likely get them to agree not to do.”

He recounted an array of encounters with some of the world’s most controversial leaders. He said that despite the in-the-gutter relationship between Israel and the U.S. today, Netanyahu had enough trust in the vice president to ask him to help normalize his country’s relations with Turkey, which had ruptured in 2010. Biden took the mission, mediating between Netanyahu and Erdogan—himself not an uncomplicated leader. And it worked. The two countries signed a deal to normalize relations this summer. Netanyahu called the vice president thanking him for his role in making their rapprochement—and a potential natural-gas deal between the two countries—work. Biden has tried to effect similar reconciliations between South Korean President Park Geun-hye and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—who at one summit of Asian leaders in 2013 spent less than 30 seconds on stage together and refused to speak with one another. Since then, the two have met several times in efforts to mend ties. Abe has visited South Korea, and Park has just announced plans to visit Japan in November. Biden gets the assist. The vice president has also spent more time hand-holding Iraq’s leaders, most recently on an hour-long call with Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi after a horrific bombing in Baghdad this summer, than any other member of the administration.

But Biden is not just glad-handing; he’s testing the waters for what is possible—and pushing leaders to do what he sees as both in the U.S. and their own nations’ interests. He described, for example, a meeting with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko—whom he calls “Petro”—in which he urged Poroshenko to fire a corrupt prosecutor general or see the withdrawal of a promised $1 billion loan to Ukraine. “‘Petro, you’re not getting your billion dollars,’” Biden recalled telling him. “‘It’s OK, you can keep the [prosecutor] general. Just understand—we’re not paying if you do.’” Poroshenko fired the official.

This personal element is, perhaps, why Biden is regularly handed the lemons in the foreign-policy sphere—the tough, unglamorous cases, the ones that have to be worked for a long time. It’s worth noting, as Goldberg has, that there are leaders Obama never really warmed up to. Biden tends these relationships. “It makes sense to give me the problems that require husbandry every day,” Biden said. “So I get Ukraine. I get Iraq. I get the relationship between Korea and Japan. I get Central America. I get Colombia. I mean—it makes sense—because he knows—the guy [Obama] is really good—he knows it’s a matter of how you broach some of these.” Whereas the former Iraqi Ambassador to the United States has said, and White House readouts of calls with foreign leaders confirm, that Obama didn’t speak to former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki for more than two years (with the exception of one brief White House visit), Biden was a frequent, consistent interlocutor. He continues to be the primary interlocutor with Abadi and many of the notables in the Iraqi political scene. On the Asia front, he’s in regular contact with Japan’s Abe about not only Korea but also the growing challenge from China. When the child migration crisis flared on the southern border of the U.S. in 2014, Biden said, Obama told him, partly in jest: “‘Look, you do the hemisphere. ... You make friends easy, and it’s in the same time zone. You can do it on weekends.’” Biden recalled replying, “‘It’s not the same time zone.’”

If Obama has always seemed more of a Russian Blue cat—smart but indifferent to other talent in the room—Biden would be the golden retriever of the administration. But the sense of White House players that I have spoken to is that Biden frequently “makes space for things to happen”—and his personal connections with leaders, and the trust that key administration personnel have in him, opens up possibilities that wouldn’t otherwise be there.

The Biden Doctrine, then, has four key components. 1) Don’t use force unless it counts and is sustainable. 2) Shore up and strengthen alliances—and build common cause on common projects with other global stakeholders. The world is changing and fragile and America can’t do all that needs to be done alone. 3) Have a sense of perspective, and think about proportional responses to threats—terrorism is not existential but nuclear exchanges are. 4) Relationships and the personal side of foreign-policy making—with allies and with enemies—is a key part of successful foreign-policy execution. It’s this fourth dimension of “personality realism” that represents the vice president’s biggest contribution, and the element perhaps most difficult for future leaders to mimic, though they would be wise to.

In a recent essay for Foreign Affairs, Biden offered a kind of summary of all he feels the Obama/Biden team has accomplished on the international front, as well as a bit of counsel to the next president. “The next administration,” he wrote, will have to contend with “uniting the Western Hemisphere, deepening our alliances and partnerships in Asia, managing complex relationships with regional powers, and addressing severe transnational challenges such as climate change and terrorism.”

That administration could very well be led by Hillary Clinton, who, Biden told me, has never been shy about asking for his input when she felt she needed it. It’s possible that some of Biden’s guiding precepts could continue to shape American foreign policy. “I’ll do anything she wants,” he said. Except maybe one thing: “I’m not going back in administration.”

NEXT STORY: A First Look Inside Border Patrol's 'Iceboxes'