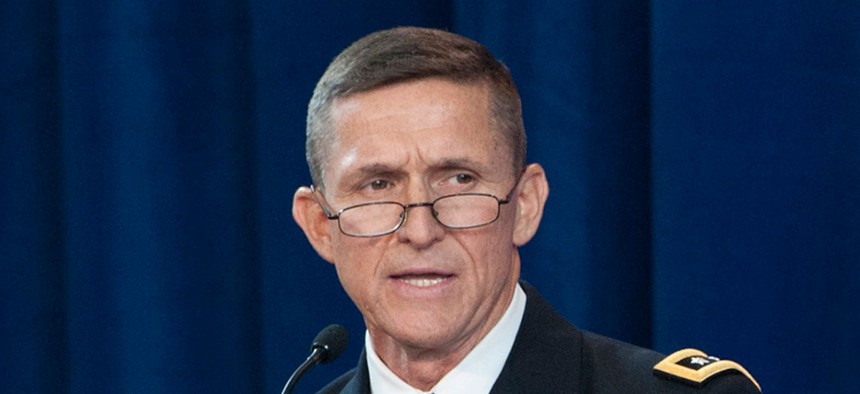

Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo/Defense Department file photo

Michael Flynn Invokes the Fifth

President Trump’s former national security adviser won’t comply with the Intelligence Committee’s demand for Russia-related documents, his lawyers said Monday.

Michael Flynn, President Trump’s former national security adviser, told the Senate Intelligence Committee on Monday he won’t comply with their May 10 subpoena of materials related to the Russia investigation, invoking his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

“The context in which the committee has called for General Flynn’s testimonial production of documents make clear that he has more than a reasonable apprehension that any testimony he provides could be used against him,” Flynn’s lawyers wrote in a letter to the committee. “Multiple Members of Congress have demanded that he be investigated and even prosecuted.”

Flynn’s response comes less than a month after the committee issued a formal demand for any documents “relevant to the committee’s investigation into Russian interference with the 2016 election.” The committee noted it had asked him to voluntarily turn over the documents in April, but his legal counsel declined.

Congress and its committees have the constitutional power to issue subpoenas as part of their legislative responsibilities. Direct defiance is rare, but not unprecedented. In the most recent high-profile episode, the House Oversight Committee voted to hold Bryan Pagliano, a former IT aide to Hillary Clinton, in contempt last year for ignoring a subpoena to testify before the committee about his role in setting up Clinton’s private email server.

But criminal prosecutions for contempt are also rare. The Justice Department can decline to pursue cases against those Congress holds in contempt, as it did in 2012 when it refused to prosecute then-Attorney General Eric Holder. The House Oversight Committee had previously cited him for withholding documents about the controversial Fast and Furious program, which it was investigating. Justice Department officials pointed to the Obama administration’s invocation of executive privilege, which shields certain categories of executive-branch communications from judicial and legislative scrutiny, when declining to take any further action against Holder.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions recused himself from Justice Department decisions related to the federal Russia investigation in March, and Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein appointed former FBI Director Robert Mueller as special counsel to oversee the probe and any related matters last week. That likely leaves Mueller to decide whether to pursue criminal charges against Flynn if Congress formally cites him for contempt.

The appointment of a special counsel, Flynn’s lawyers wrote, “creates a ‘reasonable cause to apprehend danger,’ giving rise to a constitutional right not to testify,” paraphrasing a Supreme Court ruling.

But a criminal contempt case against Flynn is unlikely after his invocation of the Fifth Amendment, which protects Americans against compelled testimony that could incriminate them in criminal proceedings. In the 2000 case U.S. v. Hubbell, for example, the Supreme Court sided with a witness in then-Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr’s Whitewater probe who was ordered to provide documents later used to convict him despite invoking the Fifth Amendment. The justices ruled that the government’s broad subpoena had unconstitutionally forced the defendant to provide documents that helped secure his conviction.

“It was unquestionably necessary for respondent to make extensive use of the contents of his own mind in identifying the hundreds of documents responsive to the requests in the subpoena,” Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for the majority. “The assembly of those documents was like telling an inquisitor the combination to a wall safe, not like being forced to surrender the key to a strongbox.”

Hubbell was among the cases cited by Flynn’s lawyer in their letter to the committee to justify not testifying. “Were General Flynn to provide responsive documents, he would be providing compelled testimony about the documents’ existence, custody, and authenticity,” they wrote. “This is precisely the sort of testimonial information that the Fifth Amendment privilege is designed to protect from compelled disclosure.”

Talking to reporters last week about the prospect of Flynn’s refusal to cooperate, Senate Intelligence Committee Chairman Richard Burr didn’t offer any hints about a potential citation. “I’m not going to go into what we might or might not do,” the senator said. “We’ve got a full basket of things we might want to test.”

Flynn, who briefly served as President Trump’s national security adviser in January and February, is increasingly at the center of the legal storm swirling around the Russia investigation. Trump fired the retired lieutenant general in February after multiple news outlets reported Flynn had spoken by phone with Sergey Kislyak, the Russian ambassador to the United States, multiple times on the same day the Obama administration announced sanctions against Russia last December.

Multiple administration officials, including Vice President Mike Pence and Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, had publicly denied any conversations took place. But Flynn’s position became untenable after news outlets reported U.S. counterintelligence officials, who regularly monitor foreign officials’ communications, had interviewed Flynn about his conversations with Kislyak in January.

Since then, he’s avoided the public spotlight but become increasingly entangled in federal inquiries into Russian interference in the last election. In March, TheWall Street Journal reported Flynn was seeking immunity from prosecution from both the FBI and the House and Senate intelligence committees before he would agree to testify. At the time, Flynn’s lawyer cryptically said his client “certainly has a story to tell.”

Neither the FBI nor the committees have granted Flynn immunity. Earlier this month, CNN reported that federal prosecutors in eastern Virginia issued grand-jury subpoenas targeting Flynn’s associates and former business records as part of the Russia investigation. Flynn is also facing a separate federal probe into lobbying payments he received last summer from the Turkish government.

Trump has frequently defended his former adviser since firing him, at one point publicly encouraging Flynn to get immunity from what the president has described as a “witch hunt” launched by Democrats to discredit his electoral victory. Flynn has also remained loyal to the president, reportedly telling associates that Trump had urged him to “stay strong” in a telephone conversation in April.

But public attention has also focused on Trump’s private conversations on the matter. Shortly after former FBI Director James Comey’s stunning ouster a fortnight ago, The New York Times reported Comey had kept extensive notes of a February conversation with Trump in which the president asked him to “let this go,” referring to the FBI investigations into Flynn. Those claims, as well as reports Trump told top Russian officials earlier this month that Comey’s dismissal had removed “great pressure” from him over the Russia investigation, stoked concerns the president may have committed obstruction of justice.

Some answers on these issues may be forthcoming. Burr’s committee announced that Comey will testify in an open hearing some time after Memorial Day in what will be his first public remarks since his firing. But after Flynn’s invocation of the Fifth Amendment, it’s unclear when the public will hear his full side of the story.