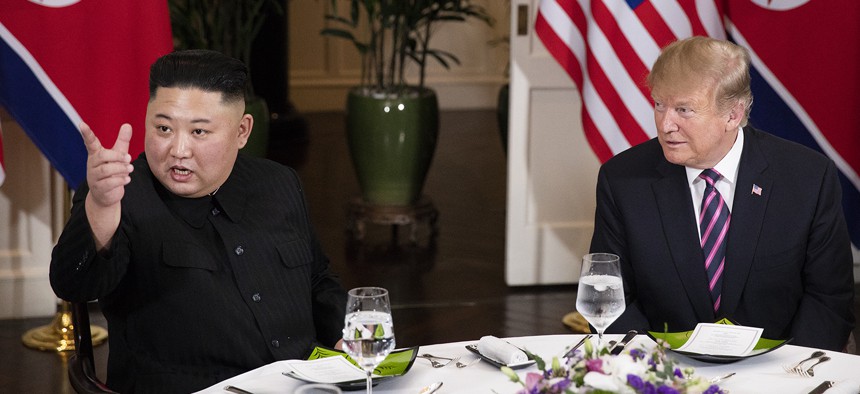

Kim and Trump meet in Vietnam on Wednesday. Joyce N. Boghosian/White House

After Raising the Stakes for North Korea Summit, Trump Walks Away

It seemed history was about to be made. Then the second meeting between the U.S. and North Korean leaders concluded abruptly.

The expectations were enormous: Perhaps Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un would, at a summit in Vietnam, finally declare an end to the Korean War, establish liaison offices in each other’s capitals, and trade the destruction of North Korea’s main nuclear facility for the easing of some sanctions against Pyongyang. There was a palpable sense that history was about to be made.

Instead, the second meeting between the two leaders ended in failure on Thursday, with a table set for a leaders’ lunch abandoned, a signing ceremony scrapped, and a terse statement from the White House press secretary: “No agreement was reached at this time.”

In a press conference pushed forward by a couple of hours, Trump revealed the sticking point that had scuttled talks: Kim wanted all international sanctions lifted as a condition for dismantling only his Yongbyon nuclear complex, which produces plutonium, tritium, and highly enriched uranium to fuel nuclear bombs. But American negotiators weren’t willing to entirely relieve the economic pressure that the United States has painstakingly amassed and maintained without Pyongyang providing a full inventory of its nuclear-weapons program and doing away with the components beyond Yongbyon, including additional suspected uranium-enrichment sites, ballistic missiles, nuclear warheads, and weapons systems.

“Sometimes you have to walk” away from negotiations, the president said during an uncharacteristically subdued appearance before the media. “This was just one of those times.” (North Korean state media has been silent so far on the summit’s collapse.)

While Trump repeated his now-familiar lines about his diplomacy with Kim—how the North Korean dictator is “quite a guy,” how their “relationship is very strong,” how a denuclearized North Korea would have “tremendous” economic potential—he did so with none of the gusto that he had at the start of the summit.

It was a stunning setback not only for U.S. efforts to reduce the threat of Kim’s nuclear weapons, but also for the administration’s signature approach to nuclear talks with North Korea.

Last March, when Trump became the first American president to agree to a meeting with the leader of North Korea, an administration official explained that the gambit was designed to avoid the pitfalls of decades of ultimately unsuccessful lower-level negotiations. The innovation was to invert the process and meet with the country’s sole decision maker.

“When I was doing the negotiations … working-level stiffs like us would be out there banging our heads against the wall, trying to get them to, oh, let us into this building at Yongbyon,” the former George W. Bush administration official Victor Cha recalled shortly before the Vietnam summit. “And critics would say: ‘You’re doing this all wrong. … You need to meet at the leader level.’ That’s what we’re doing now. We’re testing that hypothesis right now. But thus far, it looks like the product is the same thing.” Thursday’s outcome has, for now at least, confirmed Cha’s suspicions that tackling the North Korean nuclear issue from the top down hasn’t proved any more fruitful than doing so from the bottom up.

Yet Trump’s decision to choose no agreement over a bad agreement, even at the risk of embarrassing his administration on the world stage at a moment of political vulnerability at home, is also a rebuke to critics who claimed that the president would get played by Kim in Vietnam—that he was interested in only superficial success rather than substantive progress. As Trump put it at his press conference, “I could have signed an agreement today, and then you people would have said, ‘Oh, what a terrible deal’ … I’d much rather do it right than do it fast.”

The president “walked away from the opportunity to reach a flashy but poorly crafted deal,” the former U.S. intelligence official Bruce Klingner told me. Based on the president’s account, “I wouldn’t have done the deal either,” the Korea expert Joel Wit said.

The “big question is what’s next on this roller-coaster ride,” Wit added.

Having has long opposed.

Bolton’s “view and that of folks on the hard right is, the only way to do these things is through regime change,” George Perkovich, a nuclear expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told me ahead of the summit. “It’s kind of the NRA approach to gun control, which is guns aren’t the problem, bad guys with guns are, so we get rid of the bad guys.”

The deadlock over Yongbyon also exposes a profound problem in the negotiations that a senior Trump administration official, speaking on condition of anonymity, acknowledged in a briefing with reporters last week: the lack of clarity about whether the United States and North Korea have a common definition of denuclearization and whether Kim has actually made the decision to give up his nuclear arsenal. U.S. officials have long insisted that they will fully remove sanctions only when North Korea completely relinquishes its nuclear program in a verifiable manner. If Kim called on Trump to take this step just for shuttering Yongbyon, he must have a much narrower conception of denuclearization than the U.S. government does. (Asked by a reporter in Vietnam whether he was prepared to denuclearize, Kim responded, “If I was not, I wouldn’t be here.”)

“The summit’s major contribution is to move up the moment of truth that [Kim] has no intention to give up nukes,” Cheon Seong Whun, a national-security official in the conservative administration of former South Korean President Park Geun-Hye, told me. “Denuclearization diplomacy,” he argued, is dead.

The president, for his part, does not seem prepared to pronounce his diplomacy dead. Kim “has a certain vision [of denuclearization], and it’s not exactly our vision, but it’s a lot closer than it was a year ago,” he said on Thursday. “I think eventually we’ll get there.” He declined to comment on whether the United States will increase its sanctions and noted that Kim had assured him that he would continue to refrain from testing missiles and nuclear weapons, though this remains a verbal promise rather than a moratorium enshrined in some written agreement.

Both Trump and Kim are “testing whether the other could accept something significantly inferior to his original goals: arms control rather than denuclearization, some political gestures instead of full sanctions relief,” Perkovich noted when I followed up with him after Trump’s press conference. “I don’t think this is over, though if either side overreacts, it could get dangerous.”