Three soldiers burn trash from the Jaghatu Combat Outpost in a pit, located just outside the walls of the base in Jaghatu, Afghanistan in 2012. Lorenzo Tugnoli/For The Washington Post via Getty Images

Twice Burned

How the U.S. military’s toxic burn pits are poisoning Americans — overseas and at home

When Julie Tomaska stepped off the cargo plane in Balad, Iraq in 2005, her biggest fear was the daily mortar attacks. But as the 27-year-old technical sergeant in the Minnesota Air National Guard took in her new surroundings, she was struck by a more insidious threat: an enormous field of burning garbage.

Located between the dusty beige tent where she slept and the runway-adjacent trailer where she worked, the burn pit sprawled across nearly 10 acres of Joint Base Balad, a U.S. air base 50 miles north of Baghdad. Plumes of noxious black smoke rose from the pile, which contained a long list of detritus from the base’s daily operations: Styrofoam containers from the dining hall, batteries, metals, plastics, paints, petroleum products, medical waste, amputated limbs, sewage, discarded food, ammunition, and more — all of it doused in jet fuel and kept smoldering 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“You couldn’t escape the smell. The taste in your mouth. The soot in your nose,” Tomaska said. “We would just joke around and say, ‘Well, this will come back to bite us later,’ not fully realizing what that meant.”

After that deployment, Tomaska’s life was never the same. Since returning home, she has struggled with permanent lung damage. “My chest, it feels like there’s a tight rubber band, like I can’t get a full breath,” she said. She’s not alone: More than 200,000 American service members who deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan have reported health problems — such as asthma, debilitating lung diseases, and cancers — that they and medical professionals believe are connected to the burn pits. That number will likely continue to grow. The Department of Veterans Affairs, or VA, estimates that 3.5 million military members may have been exposed in the Middle East, Southwest Asia, and Africa since 1990. These numbers do not include local civilians who breathed in the same smoke.

The devastating effects of open burn pits have been well documented by the military’s own experts since at least 2006, according to reporting by the Military Times, an independent news agency. Despite these warnings, the U.S. military continued to use the practice widely until 2013. The VA has denied about 75 percent of veterans’ claims for medical and disability benefits, downplaying the connection between the massive burn pits and the growing number of people falling ill.

But overseas bases aren’t the only place where the Department of Defense has burned hazardous waste in the open air — and veterans aren’t the only ones reporting health problems.

The Department of Defense currently operates 38 toxic burn sites in the U.S., mostly in low-income, rural communities. At these sites, the military collects excess, obsolete, or unserviceable munitions, including bullets, missiles, mines, and the bulk explosive and flammable materials used to manufacture them, and destroys them by adding diesel and lighting them on fire, or by blowing them up. Last fiscal year, the Department of Defense destroyed 32.7 million pounds of explosive hazardous waste on U.S. soil using these methods, known as open burning and open detonation.

The private sector operates an additional 23 open burning and detonation facilities, which handle a range of explosives, including munitions, fireworks, and car airbag propellants. Other government agencies, like the Department of Energy and NASA, operate six more.

While the materials destroyed in overseas burn pits and at open burning and detonation sites here in the U.S. are not identical, they do release many of the same harmful emissions: acidic gases, toxic metals, dioxins, furans, volatile organic compounds, fine particulate matter, and polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs.

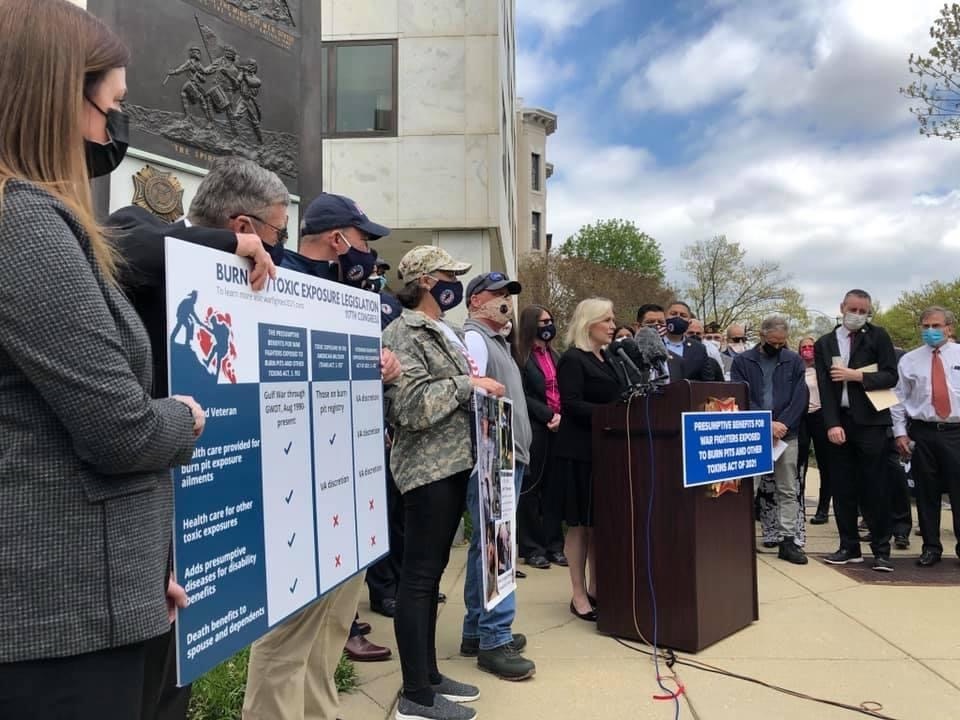

For years, veterans have been fighting the VA in a battle to ensure that those exposed to smoke from the burn pits, primarily during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, receive the medical care and benefits that they earned. Now, they have reason to be hopeful that help is on the way. The VA recently added nine respiratory cancers to the list of illnesses it assumes are caused by exposure to burn pits, meaning veterans with those cancers will have an easier time getting benefits. Last month, President Biden dedicated a portion of his State of the Union address to the issue and called caring for veterans a “sacred obligation.” Members of Congress have vowed to pass legislation before the end of the year to further expand VA benefits for veterans suffering due to a range of toxic exposures. Veterans groups are pushing hard to make sure that actually happens.

In several ways, the struggles of frontline communities in the path of smoke from open burning and detonation sites mirror those of the veterans. Both groups have had to fight to prove their health problems are linked to the open burning of toxic waste, and both groups insist that the practice must end. But while the Department of Defense has largely discontinued the practice overseas — with some exceptions — the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, shows no signs of closing the 40-year-old regulatory loophole that allows open burning and open detonation to continue across the U.S.

In the meantime, frontline communities are suffering with little recognition — and no end in sight.

When Tomaska deployed to Iraq, first in 2005 and again in 2007, she worked in intelligence for an F-16 fighter jet squadron. Her task: to analyze grainy weapons systems video footage from jets dropping bombs and launching missiles, explosion after explosion.

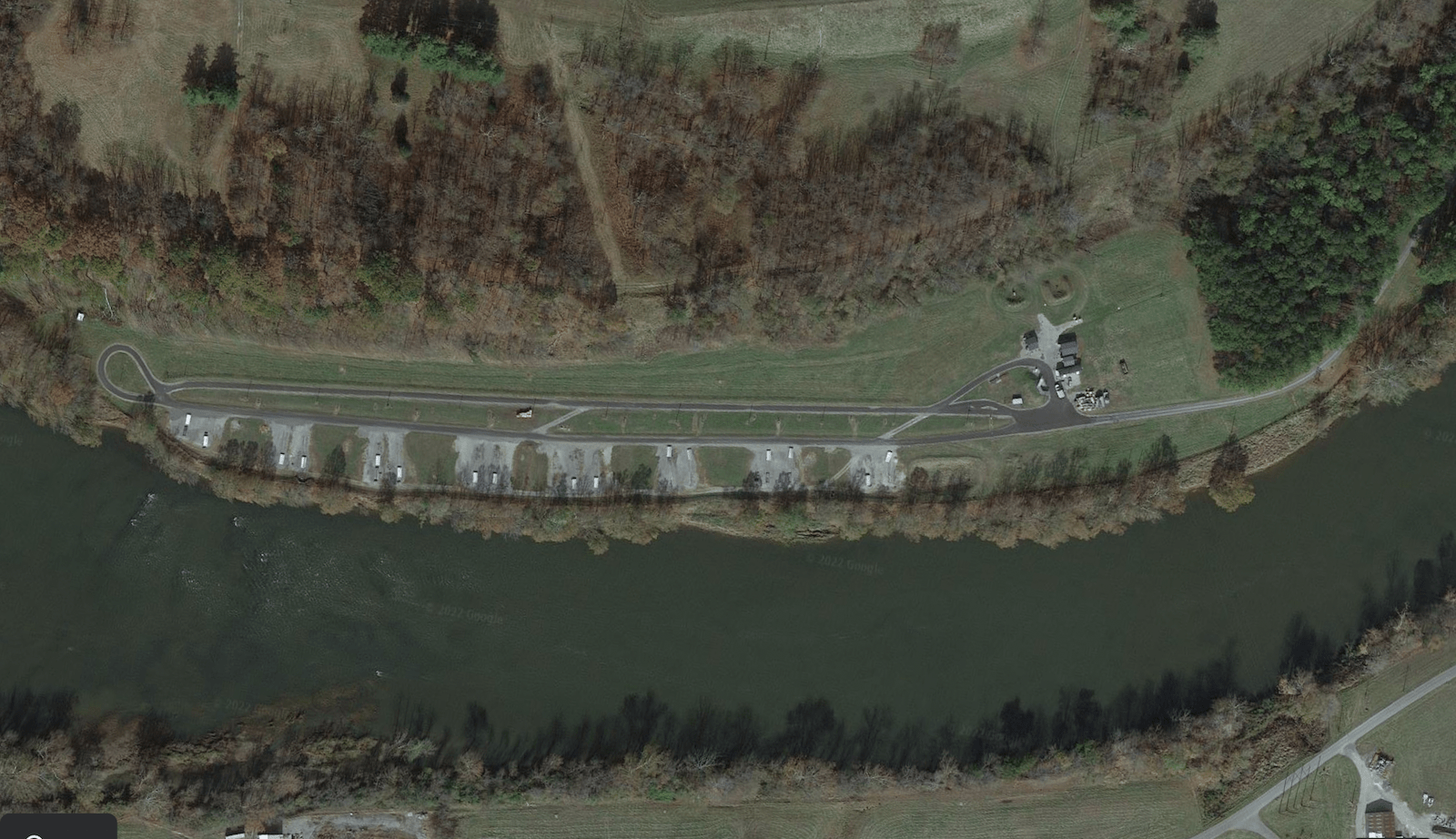

If you were to trace the origins of those munitions, one path could lead you to Appalachia. You’d come to a valley in southwestern Virginia where the New River carves a horseshoe through the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. There, you would find the Radford Army Ammunition Plant, a sprawling, 4,100-acre complex commonly referred to as the Radford Arsenal. Despite the idyllic setting, the plant regularly conducts open burning operations, unleashing a slew of toxic pollution into the air.

Alyssa Carpenter didn’t know that when she first moved into a duplex less than a mile away from the facility in 2017, but she could tell that something was off. At the time, she was a college student at Virginia Tech, six miles northeast of the plant. “I remember every morning, when I would drive over the rolling hills into town, there would be a yellowish fog,” she said.

The Radford Arsenal is owned by the U.S. Army but operated by BAE Systems, Inc., an American subsidiary of a British multinational arms, security, and aerospace behemoth. It manufactures propellants for the Department of Defense, and in 2016, the unit’s commanding officer said that a whopping 90 percent of U.S. military munitions contain material produced there, according to the Roanoke Times.

The Radford Arsenal also generates explosive hazardous waste, which it burns in two incinerators and in the open air along the banks of the New River in burn pans — shallow, rectangular troughs made of clay-coated steel. The Radford Arsenal’s open burning permit, issued by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, allows it to burn up to 5,600 pounds of explosive hazardous waste per day for up to 183 days per year, over 1 million pounds annually. On a routine basis, plumes of toxic yellow- and orange-tinged smoke rise from the banks of the river and drift over the surrounding community.

The Radford Arsenal is the single largest polluter in Virginia. According to the EPA’s toxic release inventory, the facility discharged over 10 million pounds of toxic chemicals in 2020, more than the next four largest polluters in the state combined. Not all of that is released into the air — in fact, the vast majority is released into the water — but residents are particularly concerned about what they are breathing. In 2017, the EPA and the Radford Arsenal used a drone to measure the smoke plume above an open burn and found that it contained dioxins, furans, volatile organic compounds, hydrogen chloride gas, and metals, including arsenic and lead.

When Carpenter learned about the open burning, she co-founded a group called Citizens for Arsenal Accountability, along with other concerned students and local residents. Since then, they’ve worked to inform their neighbors about the danger and to end the practice.

In 2018, Carpenter graduated from Virginia Tech and moved back home to Roanoke, Virginia. She began working as a librarian — a dream job where she could help kids reach their full potential — but something was off. She felt fatigued and sick all of the time. About a year and half after she left the Radford area, she could see her thyroid gland bulging from the side of her neck. She got a biopsy, and the surgeon told her that she needed to have it removed immediately. Her entire thyroid was diseased, and if the nodules on it weren’t cancerous already, they could be soon, he said.

In the New River Valley, Carpenter had educated community members on the fact that perchlorate — a chemical emitted by open burning at the Radford Arsenal — can disrupt thyroid function. “I’d gone to community meetings. I’d met people who were very ill. And suddenly, that person was me,” she said.

It’s difficult to link individual health problems to environmental exposures, but Carpenter feels certain that her illness was caused by proximity to the plant. Since having her thyroid removed, she’s faced a stream of health problems and endured countless medical appointments. Now 28, she’s scared she’ll never fully regain her health. “This has left me in a state of chronic illness,” she said.

Other residents strongly believe that many of the health problems they are facing — including asthma, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, thyroid cancer, and other types of cancer — are linked to toxic pollution from the open burning site.

Virginia Public Media analyzed data from the Virginia Cancer Registry and found that in the city of Radford the rate of thyroid cancer is 15.7 cases per 100,000 people, which is slightly above the national average of 14.6, according to the National Cancer Institute. Carpenter pointed out that those numbers don’t account for other thyroid conditions, and that the data may not be capturing the full scope of the problem, since about 30,000 college students at Virginia Tech and about 8,000 students at Radford University are regularly cycling in and out of the area.

“These health conditions don’t just pop up out of nowhere,” Carpenter said.

BAE Systems maintains that open burning at the Radford Arsenal doesn’t pose a risk to human health or the environment. “As the operating contractor of the Radford Army Ammunition Plant, BAE Systems continues to work closely with the U.S. Army and government agencies to comply with all environmental permits and regulations,” said Claire Powell, a spokesperson for the company. “The health and safety of our employees and our neighbors, along with the environmental stewardship of our workplace and the local community, remain our highest priority.”

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is planning to build two new incinerators for the facility, which are expected to be operational in 2026. They won’t eliminate the need for open burning, but they should significantly reduce the amount of material headed to the burn pans. Powell noted that the company has taken other steps to limit open burning and has reduced the amount of material open burned by more than 50 percent since 2018.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality also argues the open burning is safe. Gregory Bilyeu, a spokesperson for the agency, referenced a health risk assessment that BAE Systems conducted in 2020, where it modeled emissions from the burn pans and toxic exposure levels at various distances. Based on that study, the hazards from the open burning site “are below regulatory thresholds of risk to human health and the environment,” said Bilyeu.

Though the study didn’t find any serious hazards, it has some significant gaps. For example, BAE Systems identified more than 150 chemicals released by the facility’s open burning that it deemed “compounds of potential concern,” but the company included fewer than 90 of them in its analysis. (BAE Systems argued in the risk assessment that the EPA has not published enough data on how the other compounds move through the environment or on their toxicity to include them in the evaluation.)

But BAE Systems also acknowledged in the report that “it is possible that the omission of these compounds from the quantitative evaluation may underestimate the total risk and hazard to studied receptors.”

Craig Williams, a Vietnam War veteran who won the Goldman Environmental Prize for compelling the Department of Defense to adopt safer destruction techniques for chemical weapons, thinks it’s pretty simple. “Look, burning shit — burning materials — is not really what I call a state-of-the-art disposal method,” he told Grist. “It’s 2022. We’ve had people on the moon. We’ve got smart bombs that can knock a cigarette out of somebody’s mouth at a mile and a half away. But we can’t figure out a way to do this that doesn’t consciously emit toxic material into the environment?”

Williams is now part of a coalition working to end open burning and detonation across the country at sites like the Radford Arsenal and the Blue Grass Army Depot, which is near his home in Kentucky.

“When the Army says that there’s no environmental or public health impact from this process, that’s just absolute nonsense,” he said.

When Tomaska first got back from Iraq in 2005, “I just wasn’t feeling right,” she said. Though she didn’t realize it yet, like many veterans, she had experienced irreversible health consequences from exposure to burn pits — and like many veterans, she would spend years trying to navigate the VA’s convoluted system.

Tomaska scheduled an appointment with her doctor and learned that she had an elevated heart rate, but the doctor chalked it up to the stress of transitioning back to civilian life.

Two years later, with another deployment under her belt, she went back to the doctor, this time struggling with chronic fatigue. “But not shocking when you have a toddler, right?” Tomaska said. She was also attending graduate school and working two jobs.

Tomaska’s health continued to decline, and in 2013, she reached a breaking point. She was fit and not even 40 years old, but walking up a single flight of stairs left her winded.

She tried to get help from the VA. “I was in there begging for a diagnosis, just begging to know what was wrong,” she said. Despite five years’ worth of appointments, tests, and scans, no one could tell her why she felt sick and exhausted all of the time.

She began to suspect that the cause of her health issues was the smoke from the massive burn pit she’d lived next to while deployed. But doctors with the VA and her civilian health care providers insisted there was nothing wrong with her. They told her that the problems were all in her head, that she was too young to be experiencing them, and that she was just out of shape. They pointed to Department of Defense air quality monitoring studies that said evidence linking exposure to the burn pits to long-term health issues was “inconclusive.”

It didn’t take long for the scientific evidence to catch up, though. In mid-March, Anthony Szema, a pulmonologist who has conducted multiple studies on the health implications of breathing smoke from burn pits, testified before a Senate Armed Services Subcommittee. Szema said that he has diagnosed “post-burn-pit-exposed soldiers” with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, constrictive bronchiolitis, carbonaceous burned lung, titanium lung, lung fibrosis, and pulmonary ossification, or bone in the lung. “As an expert in the field, I’ve concluded that these lung disorders are directly related to exposure to airborne hazards, including burn pits,” he said.

In 2018, against the advice of her doctors at the VA, Tomaska underwent a lung biopsy at the Center for Deployment-Related Lung Disease at National Jewish Health, a hospital in Denver, Colorado. What it revealed was not good news, but it did give her some peace of mind.

“I have constrictive bronchiolitis and scarring of my lungs, like pleural fibrosis, chronic pleuritis,” she said. “Basically, everything is scarred and inflamed.”

The surgeon who did the biopsy told her he could still see the soot coating her lungs. He also found fine metallic particles in her lung tissue.

Even with the results of the biopsy – which her civilian health insurance paid for – and a diagnosis from one of the top respiratory hospitals in the country, the VA denied Tomaska’s claims for medical and disability benefits. (Not all veterans are eligible for medical care through the VA, but veterans with service-related injuries and disabilities are.) Tomaska had to hire a lawyer and go through a nearly three-year process to force the agency to acknowledge that her lung disease was service-related and that she was entitled to benefits.

Tomaska has a unique perspective on all of this. She has a master’s in public health and a doctorate in epidemiology. For 10 years of her civilian career, she worked for the VA, conducting clinical research. If anyone should be able to navigate the system, it’s her.

For veterans who don’t have the same specialty knowledge, who aren’t healthy enough to endure invasive procedures like lung biopsies, or who can’t afford to hire their own lawyer, the process is even more of a nightmare.

On March 1, Tomaska tuned in to watch President Biden’s State of the Union address. She heard him highlight one of the dangers that American troops faced overseas: “Breathing in toxic smoke from burn pits.”

When Biden called on Congress “to pass a law to make sure veterans devastated by toxic exposures in Iraq and Afghanistan finally get the benefits and the comprehensive health care that they deserve,” Tomaska’s jaw dropped. “It was surreal,” she said.

Two years ago, Tomaska retired from the Minnesota Air National Guard after 22 years of service. Despite her lung disease and related issues, she considers herself lucky. She’s still able to work and to spend time with her two teenage sons. “I have lost so many young friends to ‘rare’ cancers that have no other explanation aside from the burn pits,” she said. Her best friend, Amie Muller, who also served in the Minnesota Air National Guard and deployed to Iraq with Tomaska, died from pancreatic cancer at age 36.

Tomaska is now a board member and the scientific committee chair for Burn Pits 360, a veterans group that has been the driving force behind recent legislation. They are part of a coalition encouraging Congress to pass the Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics, or PACT, Act. The legislation would mandate that the VA expand which illnesses it assumes to be service-connected, meaning any veteran exposed to burn pits would be eligible for medical care and disability benefits for certain illnesses — without needing to go through a multi-year claim process. It would also expand benefits for veterans suffering from a host of toxic exposure injuries from past wars.

While the VA’s recent move to add nine respiratory cancers to its list of service-related conditions is a step in the right direction, Tomaska says much more is needed.

On March 3, the House of Representatives passed the Honoring our PACT Act. It faces stiff opposition from Republicans in the Senate, but lawmakers have vowed to pass some sort of legislation before the year is over.

“Words are one thing. We’re hoping to see some action,” Tomaska said.

Carpenter had a similar reaction to Biden’s State of the Union address. When she heard him bring up burn pits, she practically jumped out of her chair, shouting,“That’s what I’ve been saying! That’s what I’ve been talking about!” She was happy to hear that veterans may soon get the recognition and care that they deserve. She was also hopeful that the momentum will boost frontline communities’ efforts to stop the open burning of toxic waste in the U.S.

“If people can make the connection that this practice has harmful impacts on the health and safety of veterans, then they can also make the connection that it’s harmful to communities here, as well,” Carpenter said.

Realistically, the EPA doesn’t appear poised to end domestic open burning and detonation any time soon. In 1978, the agency proposed banning the burning of all hazardous wastes, including explosives. The Department of Defense and private companies objected, arguing that safer alternatives for destroying explosives weren’t widely available, and the agency created a temporary exception that was only supposed to be in place until new technologies were developed.

Since then, civilian groups have opposed open burning and detonation at sites across the country. In 2015, a campaign against a plan to open burn 15 million pounds of military explosives at Camp Minden, Louisiana — which would have been the largest open burn in history — brought disparate groups together to form the Cease Fire Campaign, a coalition of more than 60 organizations opposed to the practice. The organization successfully lobbied Congress to include language in the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act to force the Army, which oversees the country’s military munitions demilitarization program, to commission a study analyzing alternatives.

In 2019, the National Academy of Sciences released a comprehensive report which found that there are viable alternatives for discarding “almost all” conventional munitions. The same year, the EPA released a similar report echoing those findings.

Last year, more than four decades after the EPA created the exception, the agency began a rule-making to update the regulations that govern open burning and detonation. In light of the recent reports, “we are taking a fresh look at the existing requirements,” said Carlton Waterhouse, deputy assistant administrator for EPA’s Office of Land and Emergency Management. This spring the EPA will issue a policy memorandum to clear up any confusion about existing permitting regulations. Later, through the rule-making, the agency intends to “further clarify” requirements for open burning and detonation facilities, Waterhouse said.

Frontline communities involved in stakeholder meetings with the EPA are deeply skeptical that the agency will significantly reduce the amount of hazardous waste being open burned and detonated in their backyards.

Carpenter hopes the agency will do much more to end the practice and the toxic pollution that it’s unleashing on communities like hers. “What I want people to know — what I need people to know — is that it’s not just happening other places. It’s happening here, too. It’s happening in our backyard. It’s happening to our neighbors,” she said.

“There is no safe way to burn toxic chemicals.”