Twenty years after the Oklahoma City bombing, and the only thing we really know for sure is that 168 people should not have died.

By Kellie Lunney

We think of time around major events, particularly traumatic ones, as Before and After. It’s one way we make sense of the incomprehensible.

Before Sept. 11, 2001, we lived in an America that was post-World War II, then post-Vietnam, then post-Cold War. Now, we live in post-9/11 America. But before Sept. 11, 2001, there was April 19, 1995, the day that 168 people, including 19 children and 90 federal employees, were murdered when Persian Gulf War veteran and upstate New York native Timothy McVeigh blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The stated “reason” was in retaliation for federal law enforcement’s disastrous response to a standoff with a fringe religious group at the Branch Davidian complex near Waco, Texas, in 1993, and a showdown with a white supremacist in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, in 1992. Both events resulted in casualties, many of them children.

The Oklahoma City bombing was the worst incident of domestic terrorism to date in America, and it was aimed squarely at the federal government. Except, “it wasn’t the government that suffered, it was our society,” says LeAnn Jenkins, executive director of Oklahoma’s Federal Executive Board for the last 21 years. “It was a lot of families.”

For Oklahoma City’s survivors, its dead, and their families, there is a very real Before and After. Their world was completely different at 9:03 a.m., the minute after the bomb was detonated underneath America’s Kids daycare center on the building’s second floor, than it was at 9:01 a.m.

They didn’t get a say in it.

It wasn’t the government that suffered, it was our society.LeAnn Jenkins, Executive Director of Oklahoma’s Federal Executive Board

April 19, 1995, also was, in some ways, the dawn of the current chaos that we—the American public, the government—have desperately tried to bookend order around, with mixed success. America is a different place today than it was in 1995, primarily because of technology. Some things, however, remain largely unchanged: namely, an antipathy toward the federal government that manifests itself in the hate perpetrated by the militia movement and white supremacists, but also in politically expedient, at-large, fed-bashing by both Republicans and Democrats.

“Today’s anti-government rhetoric is more ubiquitous and disturbing than in the past. One reason is that the fringe groups seem to have become more a part of the fabric of society, thanks in large part to advances in communications that allow them to spread their rhetoric instantaneously to a potential audience of millions. Another reason is that verbal attacks on federal employees are seeping into every crevice of society. Members of Congress have chosen the same vicious language as the NRA to belittle federal employees working in law enforcement, land management and tax collection.”

That excerpt is from a July 1995 Government Executive story called “Raging Rhetoric.”

In May of that year, President Bill Clinton, in deference to the victims of Oklahoma City, said he would never “knowingly” use the term “government bureaucrat” again. Public officials are slightly more politically correct these days—and they certainly are immediately after tragic events like Oklahoma City and 9/11. But negative sentiments about the federal workforce are still very much around in 2015, as is use of the term “government bureaucrat.” Just Google it.

The same 1995 issue, in the cover story “Vitriol and Violence,” mentions a Nevada rancher named Cliven Bundy who refused to pay federal grazing fees.

“The BLM [Bureau of Land Management] says it hasn’t attempted to impound the cattle because it fears violence. Bundy has threatened to ‘do whatever’s necessary to defend my land.’ A Forest Service official says Bundy once told a crowd of ranchers that the United States was founded on fighting and bloodshed and that ‘peaceful solutions are not enough anymore.’”

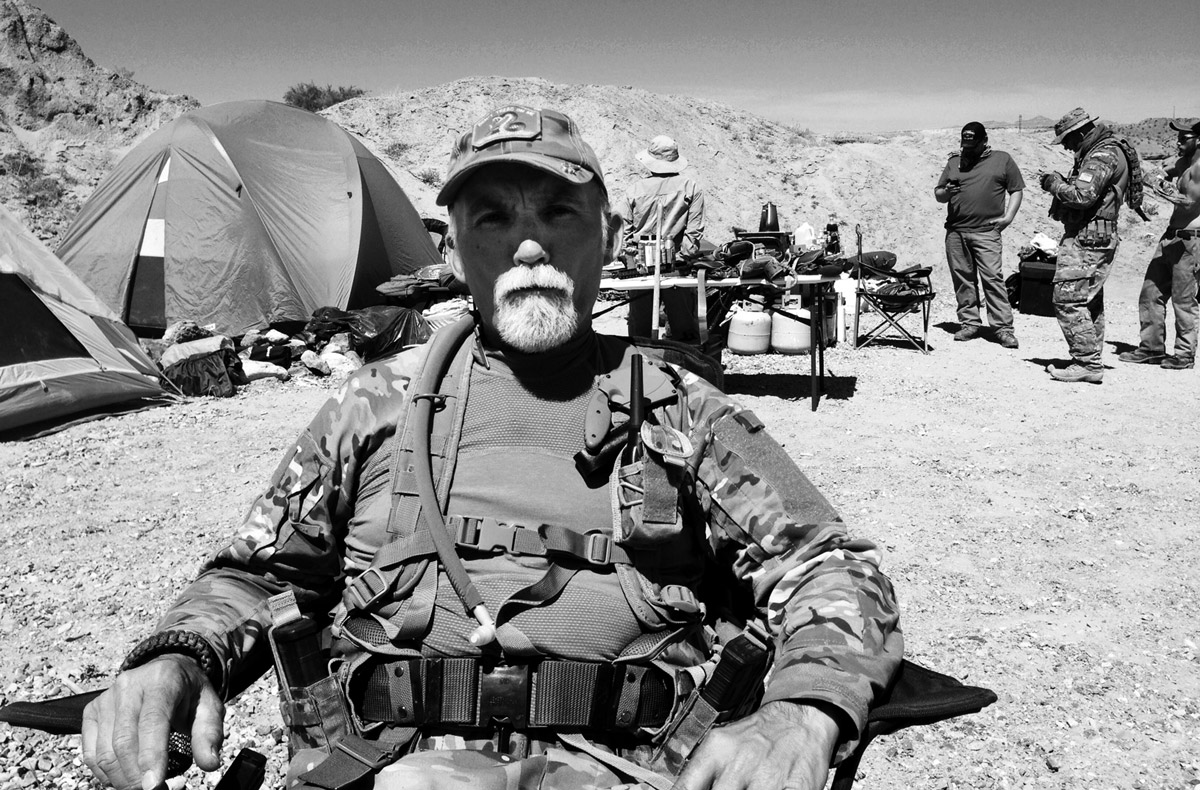

Fast-forward to April 2014, when armed militia members flocked to Nevada to support Bundy in the continuing battle against the BLM. After a prolonged standoff, the agency capitulated to the mob, and released the cattle. From an April 10, 2015, Government Executive story by Eric Katz:

“In the months since the Bundy standoff, many Nevada ranchers have ignored BLM warnings to curb grazing activities while record droughts afflict the state and region. Now BLM employees are unsure where they stand, should new fights evolve.”

Twenty years later, and we’re still dealing with Cliven Bundy and his ilk.

For Jenkins, the two decades since the Oklahoma City bombing alternately feel like yesterday and “a long, long time ago,” especially since there are so many “new” federal employees for whom the Oklahoma City bombing is merely history, something that happened before their time. So Jenkins and others who were around in 1995 are “trying to enhance, heighten awareness and sensitivity on things that normally would go by the wayside, like the anti-federal employees rhetoric. In some places, it’s like, you kind of expect that,” Jenkins says. “Well here, we have a sensitivity to that.”

Other remnants of 1995 are still with us, in spite of Oklahoma City and 9/11. Yes, our federal buildings are more physically secure, and “continuity of operations plans” more prevalent. As employees who work in homeland security, law enforcement and intelligence like to say, "no one ever hears about the crises averted, only the screw-ups." And certainly, there have been crises averted since Oklahoma City and 9/11 (the Shoe Bomber, the Underwear Bomber). But there are still epic turf battles and a lack of communication among federal agencies—and between federal, state and local governments—that hamper intelligence-gathering and the apprehension of people who pose real threats to this country, home-grown and otherwise (the Boston Marathon Bombers). Law enforcement at every level of government too often reacts politically, or disproportionate to the situation, sometimes overzealously, sometimes not all.

The definition of bureaucracy is “a system of government or business that has many complicated rules and ways of doing things,” according to Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary. That’s a pretty apt description of the federal government. But the federal government is also a system run by people. People with lives, families, friends; people with names and faces. Public servants and institutions should always be held accountable for their words and actions, for malfeasance and incompetence. But accountability must come through the established mechanisms of democracy. As imperfect and unsatisfying as those mechanisms can be, they will always be superior to revenge and violence.

On the 19th of April, 1995, 168 people lost their lives for no reason. This shall never be forgotten.The Oklahoma Department of Civil Emergency Management After Action Report

The Oklahoma Department of Civil Emergency Action issued a report after the 1995 bombing that was thorough and clinical in detail. Exact response times, maps of the Murrah building showing where federal agencies were located (the Secret Service and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms were on the ninth, top floor), even the number and type of injuries sustained by victims who were hospitalized after the bombing (lacerations, abrasions and contusions: 77; eye injuries: 21).

But one poignant and incontrovertible fact in the report stands out among all the rest: “On the 19th of April, 1995, 168 people lost their lives for no reason. This shall never be forgotten.”

Kellie Lunney covers federal pay and benefits issues, the budget process and financial management. After starting her career in journalism at Government Executive in 2000, she returned in 2008 after four years at sister publication National Journal writing profiles of influential Washingtonians. In 2006, she received a fellowship at the Ohio State University through the Kiplinger Public Affairs in Journalism program, where she worked on a project that looked at rebuilding affordable housing in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina. She has appeared on C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, NPR and Feature Story News, where she participated in a weekly radio roundtable on the 2008 presidential campaign. In the late 1990s, she worked at the Housing and Urban Development Department as a career employee. She is a graduate of Colgate University.