IT'S TOO HARD TO DISCIPLINE OR REMOVE POOR-PERFORMING FEDERAL EMPLOYEES, CRITICS SAY.

BUT WILL THE SYSTEM EVER CHANGE?

BY ERIC KATZ / ILLUSTRATIONS BY WILL MULLERY

Sharen Greene serves as a taxpayer advocate at the Internal Revenue Service. Nowhere in her job description is the word “baby sitter.”

But that’s exactly what Greene, a career civil servant in Albany, New York, wound up doing when an employee with a drinking problem was unloaded on her office. “Every single day I had to escort him out of the building for being inebriated,” Greene says. “It was evident. It was obvious.”

Agency managers never dealt with the employee. In Greene’s estimation, they determined it was easier to, quite literally, push the problem to the corner. Greene’s horror story is an extreme example of the way many people perceive the federal government: It is nearly impossible to remove an entrenched, poorly performing or even malfeasant federal employee. The red tape is too thick to penetrate. The bureaucracy protects itself.

Even the Office of Personnel Management, the federal agency charged with creating and enforcing governmentwide human resources policy, concedes there is a pervasive sense that firing a fed is difficult. “The procedures for terminating employees are perceived as a lengthy process,” says Tim Curry, OPM’s deputy associate director for partnership and labor relations.

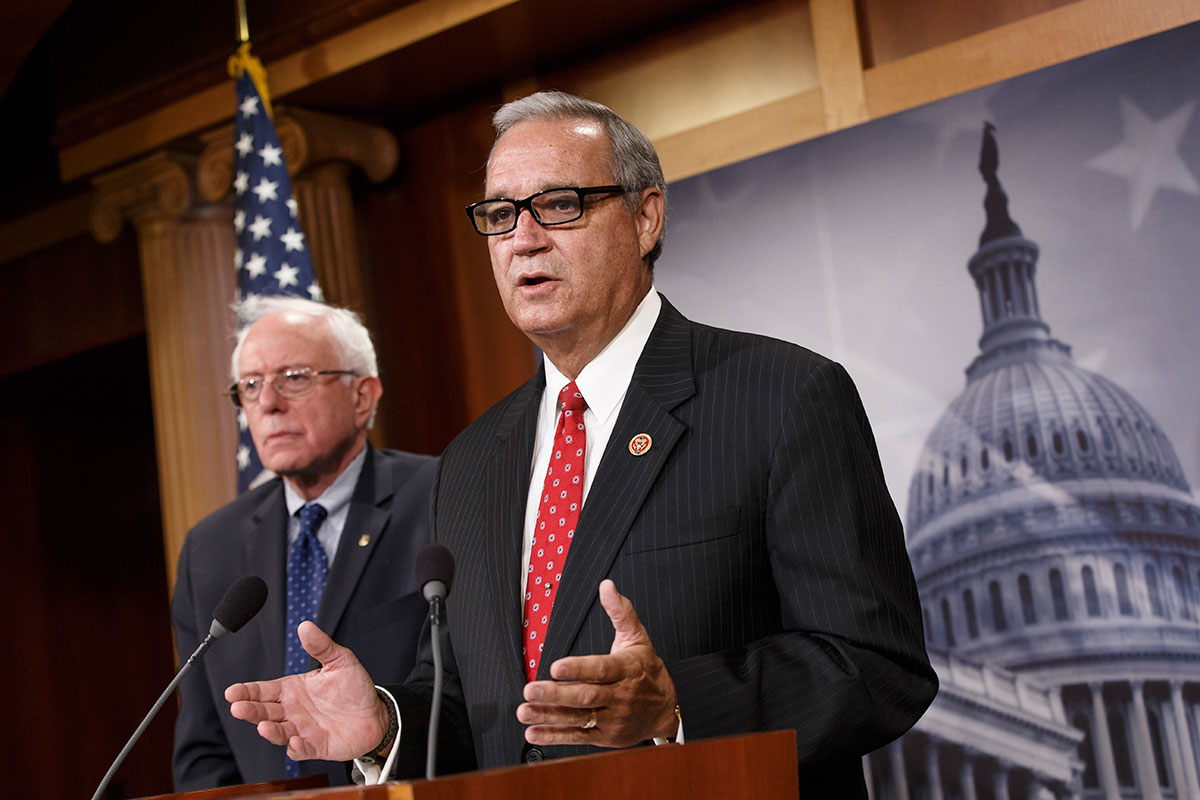

I believe it was easier for managers to move individuals into other positions than it was to discipline them or fire them.REP. JEFF MILLER, R-FLA.

Undoubtedly, there are major hurdles to removing an employee from federal service; federal workers are guaranteed levels of due process not typically provided to employees in the private sector. Whether that’s a problem is the subject of a lengthy and nuanced debate, but the mere perception that incompetent federal employees operate with impunity creates fractures that divide agencies from their workforces, the legislative branch from the executive branch, managers from their employees and the American people from their government.

“Whether or not it is a fair statement,” says Dan Blair, president and CEO of the congressionally chartered National Academy of Public Administration, “it becomes reality.”

A survey of federal employees and managers conducted by Government Business Council, Government Executive Media Group’s research arm, buoys that notion; when asked how their agencies deal with poor performers who cannot or will not improve after receiving counseling, just 11 percent of respondents said the employee is fired. Nearly eight in 10 agreed that federal termination procedures “discourage the firing of poor performers.”

So while there is near-universal recognition that agencies have a problem getting rid of subpar employees, absent a headline-grabbing scandal such as the lavish conferences thrown by the General Services Administration early in the Obama administration or the more recent, systemic issue of patient data manipulation at the Veterans Affairs Department, there’s little political will to tackle the unsexy issue of civil service reform. The law governing employee removal procedures—the 1978 Civil Service Reform Act—has remained largely unaltered for more than 35 years. There’s also little agreement on what any changes should look like.

Any attempt to modify firing procedures in the federal government is met with an immediate outcry that reforms will revert the civil service to a spoils system in which fair hiring is replaced with political patronage and each new administration disrupts the basic functioning of government by distributing pink slips en masse to the previous president’s workforce.

How to keep the system apolitical has itself become the most politicized aspect of civil service reform. To some, the convoluted process of dealing with poor performers in government is the major burden holding back an effective bureaucracy; to others it’s the only thing holding it together.

“We certainly don’t want to return to an age where . . . employees are being hired or fired for political reasons and actions are being taken against federal employees solely due to political pressure or abuse of politicians,” says a House Democratic aide who works on federal workforce issues.

Rep. Jeff Miller, R-Fla., chairman of the House Veterans Affairs Committee and author of a new law that makes it easier to fire senior executives at VA, does not disagree with that sentiment, but he says sometimes the only way to incite change is to fire bad apples.

“One of the surest ways to change a culture is through holding people accountable,” Miller says.

How to Fire a Fed

All new federal employees start their jobs with a one-year probation period. During that period, many of the hurdles that prevent the quick removal of most government workers do not apply. Curry says OPM encourages managers to take advantage of that window to weed out poor performers.

Employees who survive their first year are immediately entitled to many protections. Federal workers can be fired for poor performance (those who simply can’t do the job) or misconduct (those who break the rules, including while off the clock), but in either case they are entitled to due process and other rights.

Many poor performers will be given a performance improvement plan, in which a manager, in conjunction with the agency’s HR office, will spell out steps to correct problems. Governmentwide guidance on these plans is loose, and allows for each agency to take into account its own policies and requirements. Some agencies allow managers to modify flexible work arrangements, such as cutting off telework agreements so the problem employee is under stricter supervision.

If performance still does not improve, managers can take more drastic steps. They can write a letter of admonishment that goes into the employee’s official record, reassign the worker (which is not considered an adverse action), demote the employee, or remove the worker from his or her job.

Employees facing an adverse action must by law be given 30 days’ notice. They are notified of their right to reply, obtain representation and review materials used in the case against them. During this period they may provide medical documentation explaining a lapse in performance and file an appeal. Workers with union representation can file a grievance against the manager to start the appeal process, while others can take up their issue with the independent, quasi-judicial Merit Systems Protection Board.

Rep. Jeff Miller (right) has pushed to overhaul VA and fire poor performers, along with Sen. Bernie Sanders.

In a typical year, MSPB receives 5,000 to 6,000 cases. In addition, more than 15,000 federal employees filed discrimination complaints against their agencies in fiscal 2012, the latest year for which data are available. About 8,000 of those led to hearings at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. To further complicate the process, some of these cases can appear before both the EEOC and the MSPB. A third independent agency tasked with protecting whistleblowers, the Office of Special Counsel, also can delay proceedings at MSPB to launch its own investigations.

MSPB cases are initially decided by an administrative law judge at one of the agency’s regional offices, after a discovery period and a hearing. The judge determines whether the employee was justifiably removed to “promote the efficiency of the service.” About one in 10 of those cases are further appealed to the central, presidentially appointed, three-member board.

Sixty percent of all cases settle at the regional level. A settlement could include a range of outcomes, such as a monetary award in exchange for leaving the agency or an expunged record. A judge may also reduce the severity of the punishment: Firings can become suspensions, and suspensions can turn into letters of reprimand.

Agencies and employees can agree to wipe any wrongdoing from an employee’s record, so long as the employee agrees to resign from the agency. This is one factor propelling the revolving door of poor performers in government: Employees can quit their job without any indication of a problem and then apply for work at a different agency, or even a different office in the same agency, with a clean slate.

It’s not impossible todavid borer, afge general counsel

fire a federal employee.

It happens every day.

Agencies also sometimes force an employee into a position at another office or department. In the Government Business Council survey, 27 percent of respondents said poor performers who received counseling to improve but failed to do so were transferred. Anecdotally, federal managers tell Government Executive some problem workers are actually given good reviews so they get promoted and the reviewing manager no longer has to deal with them.

The issue of transferring gave rise to the VA reform. “I believe it was easier for managers to move individuals into other positions than it was to discipline them or fire them,” Miller says.

One-quarter of the cases that avoid settlement are reversed or mitigated, meaning just 30 percent of all adverse action cases brought to MSPB are upheld without compromise. Alan Lescht, who runs a law firm that represents federal employees at MSPB proceedings, says it is often not difficult to “poke holes” in an agency’s case, because there are “a lot of technical arguments” employees can make.

All told, the average appeal case takes 93 days to wend its way through MSPB review, during which time agency managers, attorneys and human resources staff are intermittently diverted from focusing on mission-oriented work. Cases that make it to the central board take significantly longer.

MSPB does not deny the process is lengthy and difficult to navigate.

“Is it a reality or not?” says Susan Grundmann, MSPB’s chairwoman. “It’s a process. It’s the process that Congress designed for us to use.”

Balancing Act

Not everyone believes the maze of federal employees’ due process is too complex.

“The whole idea of this discussion is founded on a false premise,” says David Borer, general counsel at the American Federation of Government Employees. “It’s not impossible to fire a federal employee. It happens every day.”

Indeed, more than two dozen federal employees are fired every day, on average. The number of feds removed for performance or conduct hovers around 10,000 individuals annually, according to OPM statistics. Still, the government firing rate in 2013 was 0.47 percent. Private sector workers are three times more likely to be terminated than their federal counterparts, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Is the disparity proof the federal system protects employees who can’t or won’t do their jobs? Or does it illustrate the rigor of a federal hiring process that weeds out most poor performers before they even start?

For NAPA’s Blair, who served for several years as OPM’s deputy director (and a brief stint as director) under President George W. Bush, the answer lies somewhere in between, and any fixes will require a balancing act. “When it takes an inordinate amount of time for the manager to focus his or her attention on one employee at the expense of other employees,” Blair says, “it would seem to me that there’s a problem with the system.”

Part of the balance will involve a renewed effort to force managers to hold employees accountable. “No one has ever broken their arm trying to fill out the paperwork,” Borer says. “No decent manager worth his or her salt should have any concern about having their decision reviewed by a third party.” The House Democratic aide says agencies can already deal with poor performers “if they want,” adding, “it’s just a matter of implementation.”

Consequences of Inaction

One employee at the Defense Contract Management Agency, who spoke on condition of anonymity so he could openly discuss problems at his office, says he consistently sees people sleeping on the job, and everyone is aware of it. Some of those employees are constantly late and do not complete their work.

Yet they remain on the job, and their positions have never been seriously threatened. Why?

“Management is either too complacent or too lazy,” the employee, an industrial specialist, says. He adds that when he previously worked in the private sector, “If they have an issue with someone they walk them out the door.”

When a worker does not do his or her job, someone else has to pick up the slack. “It decreases the morale of employees who see that and see nothing is happening,” says Greene, the taxpayer advocate at IRS.

OPM’s Curry says managers must be proactive and openly communicate expectations to nip problems in the bud. This has the dual benefit, he says, of reducing the burdensome process if an employee does not improve. OPM conducts training sessions, in classroom settings and online through its HR University, to help managers and human resources practitioners improve these skills.

Michelle Linn, a civilian manager in the Installation Management Division of the Air Force, says she spends extra time with struggling workers. “All employees can be successful or not depending on the support they are given,” Linn says. She adds that budget cuts have increased the pressure on her division: “Failure is not an option. We can’t afford it.”

Of course, engaging in these training sessions and following Linn’s model is time-consuming. For a good manager, though, that should come with the territory. “Whether the supervisor likes it or not, that’s the job the supervisor signed up for,” says MSPB’s Grundmann. “There’s good times and then there’s conflict.”

What Will Reform Look Like?

The momentum for more sweeping reform is growing.

“Human nature is if a person who works beside you is doing half the work and getting paid the same amount of money, you’ll begin to question if you need to work as hard as they do or if you need to be as accurate in your product as they are,” Miller says. “People need to all strive for the best, not for mediocrity. There is a culture in some places in the federal government that mediocrity is acceptable. It is not.”

Even agency heads such as Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Gina McCarthy and VA Secretary Bob McDonald have implored Congress to give them more authority to dismiss poor performers. Amidst scandals at VA, EPA, IRS and other agencies, the pendulum on Capitol Hill is clearly swinging toward loosening the protections currently afforded to the federal workforce.

Miller calls his VA legislation a “test case” for the rest of government.

“This, we hoped, would become a template for future legislation that would allow accountability within the ranks of federal service,” he says. “Certainly poor performing employees are not only in the VA. They are found at every level of the federal government.”

We want the bad employees who are gaming the system and perpetuating this culture within the federal government to find somewhere else to work.REP. JEFF MILLER, R-FLA.

The House did not wait to see the test results before passing in September a bill to expand the firing authority included in the VA law to all departments. The measure floundered in the Senate, but will likely face a much friendlier reception with the chamber’s new Republican majority.

The Democratic aide said her party wants to work with Republicans to better enforce the laws already on the books as well as move legislation to “improve the process” and “make things go more quickly.” She stopped short of endorsing a VA reform expansion.

“That’s why these civil service protections are in place, because unfortunately there will be scandals,” she says. “These protections were put in place to prevent the sort of automatic knee-jerk reaction of ‘OK, let’s fire everybody’ based on political pressure or public outrage.”

Other possible reforms include giving agencies more flexibility in docking pay or considering performance when reducing staff as a result of budget cuts. Blair says the most important thing is harnessing the current momentum to get the conversation started. In each of his last three budget proposals, President Obama has suggested creating a commission to find ways to modernize the civil service, including “personnel performance and motivation.” The commission has yet to receive funding.

Blair adds that even if civil service protections are lifted or loosened, the system will be self-regulated, because good employers will know that “wholesale getting rid of employees” is disruptive to the workplace.

The goal, after all, has never been to punish the overwhelming majority of federal employees committed to public service. “We want good employees to be protected,” Miller says. “We want the bad employees who are gaming the system and perpetuating this culture within the federal government to find somewhere else to work."

Eric Katz joined Government Executive in the summer of 2012 after graduating from The George Washington University, where he studied journalism and political science. He has written for his college newspaper and an online political news website and worked in a public affairs office for the Navy’s Military Sealift Command. Most recently, he worked for Financial Times, where he reported on national politics.