.jpg)

A 2015 survey of attitudes toward post-9/11 military veterans showed respondents three photos: a clean-cut, professional-looking man wearing a shirt and tie sitting at a laptop; a guy dressed in a tee-shirt and overalls leaning over the open hood of a car; and a disheveled, dirty man sitting on the ground holding a sign that says “Please Help. God Bless.” Respondents assigned a list of traits to each picture, including “military veteran.” Sixteen percent of respondents thought the computer guy was a veteran, while 23 percent said the auto mechanic was a vet.

Forty-four percent of respondents said the “homeless” man was a veteran, though there was nothing in the picture to indicate he’d served in the military.

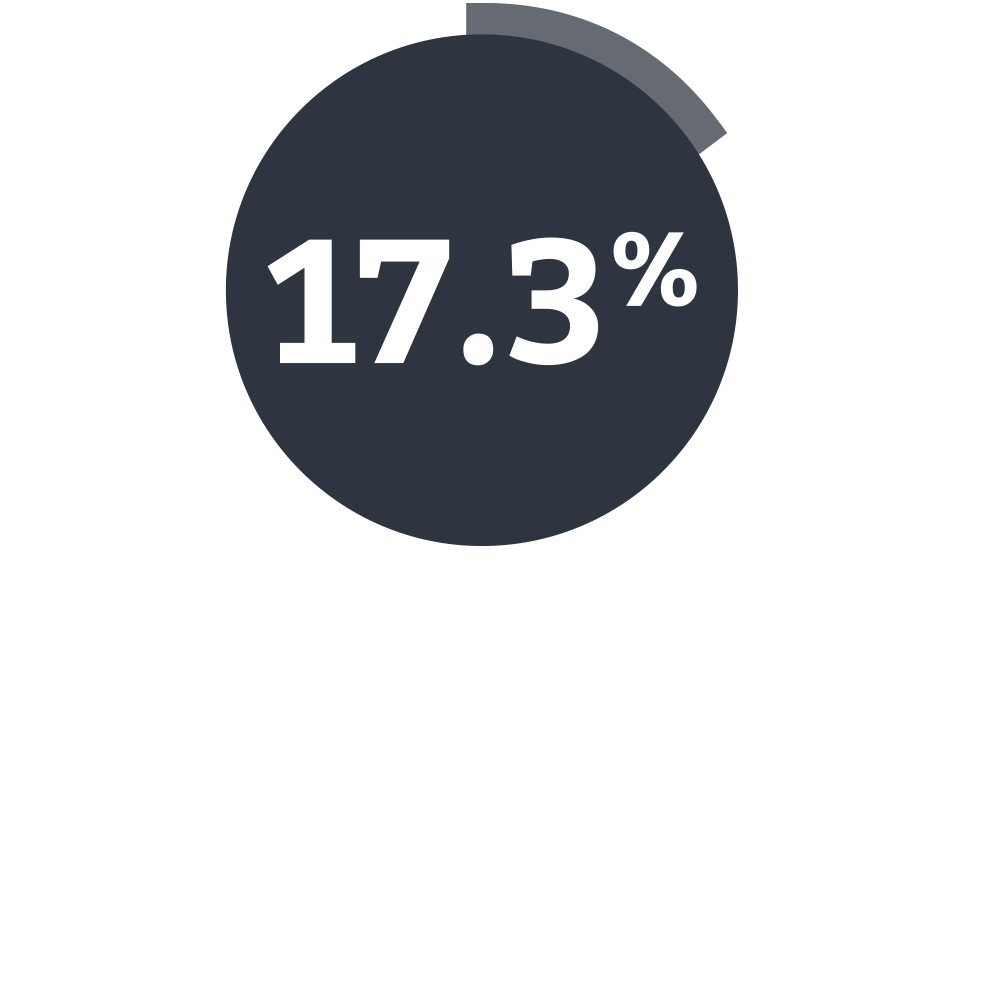

In the same online survey, 67 percent of respondents said “hero” aptly described a post-9/11 veteran, compared to 35 percent who chose “damaged” and 27 percent who picked the adjective “homeless.”

The survey, conducted by Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research on behalf of the veterans’ empowerment group Got Your 6, illustrated the split perception many Americans—including vets themselves—have of military veterans as broken heroes. The public’s trust and confidence in the military has remained relatively high over the past several years, especially compared to other institutions. An October Pew survey found that 79 percent of Americans had either a great deal or a fair amount of confidence that the military will act in the public interest.

But once service members hang up their uniforms, for many Americans, the image of the tough, resilient warfighter morphs into a fragile, damaged victim beset with post-traumatic stress disorder and dependent on the government. “Fewer people today know veterans than ever before, and so they are more susceptible to this false narrative that veterans are broken,” says Bill Rausch, an Army veteran who served in Iraq and is now executive director of Got Your 6. “It’s easy to think someone is broken if you don’t know them.”

Bill Rausch, executive director at Got Your 6, speaks at the group's "Storytellers" event, in advance of Veteran's Day at the Television Academy's Wolf Theatre at the Saban Media Center on Nov. 1, 2016, in North Hollywood, Calif. (Photo by Danny Moloshok/Invision for the Television Academy/AP Images)

Phil Klay, a Marine Corps vet who served in Iraq and won a 2014 National Book Award for his short story collection Redeployment, says there is an assumption among civilians that “if you served, it must have been a uniformly negative experience,” or that you were “either a Navy Seal superhero or a passive, traumatized victim.” Klay, who spoke during a July Brookings Institution event on the evolving role of the soldier and the state, recounted a conversation with a fellow Marine vet who had PTSD: “He said, ‘I don’t tell war stories because people only want to hear about the worst things that happened to me. They don’t want to hear about the guys I left behind in my unit, the good times we had, or hell, what the biggest barracks rat I ever saw was.’ In some ways, it is safer for us to section it off,” Klay said.

Still, civilians aren’t the only ones who can breathe life into clichés. “I think there is a victimization narrative, and I do think some veterans play into it,” said Klay. “Veterans are as guilty as anyone else in contributing to false narratives sometimes.” Rausch agrees that sometimes vets’ groups exacerbate the problem for their own self-interest. “I think there are some people who talk out of both sides of their mouth. They’re saying, ‘Hey, we’re all killing ourselves, so give me money.‘ ” But, he says, he sees “a conscious effort and shift among organizations that are growing, that are healthy, where that isn’t the case.”

Of course, many veterans battle PTSD, suicide, homelessness, substance abuse, and a range of physical and mental health issues resulting at least in part from the stresses of their military service. The government, health care professionals, and the public are much better educated today than ever before on how to care for veterans and provide the services they need and deserve. But non-veterans have all the same problems vets do, and on a much larger scale, because there are more of them. It’s more likely for an American to know a non-vet than a vet who has struggled with one or more of these issues. Yet somehow, many of us fail to see the connection and tend to think of these societal ills as only vets’ problems.

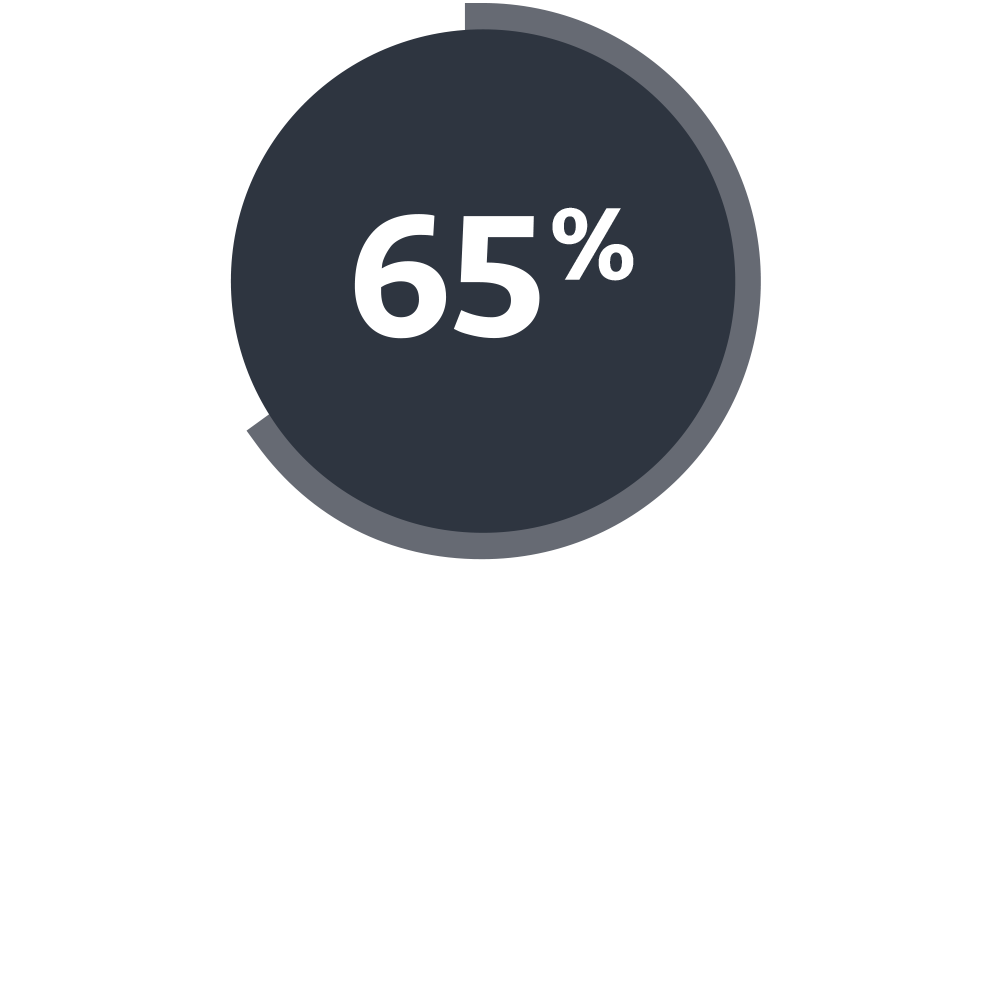

Take suicide, for example, the tenth leading cause of death in this country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Veterans Affairs Department this past summer released the most comprehensive study to date on veteran suicide, which showed that on average 20 veterans a day kill themselves. Sixty-five percent of vets who died from suicide were age 50 and older in 2014, according to the data; of the 42,773 people in the U.S. who took their own lives in 2014, 7,403 were veterans.

“It is a tragedy that we are losing military people to suicide,” said Tom Berger, a former Navy corpsman with the 3rd Marine Corps Division in Vietnam who has a doctorate in mental health and has studied suicide extensively. “Yet, look at the civilian statistics: We truly have a suicide epidemic,” says Berger, adding that the focus, however, is on the military. On average, 93 civilian adults per day died by suicide in the U.S. in 2014, up from 62 per day in 2001, according to the VA study.

“We’re all in this together, folks,” Berger says. Even if we don’t always see it that way.

Third Rail Issues

Long gone are the days when service members returning from the Vietnam War got grudging government assistance gift-wrapped in their countrymen’s spit and vitriol. Veterans, particularly post-9/11 vets, now find themselves in a curious place in the American public’s fevered imagination. They’re revered, yet feared, lionized, but just as often infantilized. The veteran community, which totals around 22 million right now, arguably has one of the most powerful voices in Washington, but many still believe the public stereotypes of them as damaged, or worse, while elected officials sometimes use them as “political chew toys” to advance their own agendas and careers.

U.S. Airmen salute during a ceremony in Picauville, France, on the 70th anniversary of D-Day, June 6, 2014. (DoD photo by Staff Sgt. Sara Keller, U.S. Air Force/Released)

“What people don’t realize, especially on the [Capitol] Hill, if you look at veterans as a special interest group, you don’t get it, frankly,” says Rausch. “If you look at the special interest groups or caucuses that exist—Asian-American, African-American, LGBTQ—if you did a veterans’ caucus event, you know what you would have? People from each one of those come to our events because we represent all of those communities,” the Ohio native says. “None of us are born veterans, we make a decision to join the military.”

But there is no question that veterans and their advocates have successfully lobbied Congress over the years, whether it’s to protect or expand their benefits, improve the Veterans Affairs Department, or incentivize the private sector to hire more veterans—and that’s the very definition of a special interest group. Veterans’ issues are something of a sacred cow in Congress these days, and lawmakers who oppose vets-related legislation, regardless of the reason, risk being tagged as “anti-veteran.”

In 2014, then-Sen. Tom Coburn, R-Okla., was roundly criticized for blocking a vote on the Clay Hunt Suicide Prevention for American Veterans Act, legislation (eventually passed by Congress) that called for expediting vets’ access to mental health professionals and required a third-party evaluation of the existing suicide prevention programs at the Defense Department and the VA. Coburn, who was known as “Dr. No” among his colleagues for his frequent opposition to legislation, particularly legislation with high-price tags, argued that the bill was redundant because VA already had the money and authority it needed to improve suicide prevention, and that ultimately the measure wouldn’t do what it set out to do.

“Regrettably I object to this bill, not because I don’t want to help save suicides, because I don’t think this bill is going to do the first thing to change what’s happening,” Coburn said on the Senate floor in December 2014, shortly before he retired. The Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, a group that had lobbied vociferously for the bill named after a Marine Corps combat veteran who killed himself in 2011, went after Coburn hard. “It’s a shame that after two decades of service in Washington, Sen. Coburn will always be remembered for this final, misguided attack on veterans nationwide,” said IAVA CEO and Founder Paul Rieckhoff in a Dec. 15, 2014, statement.

Rausch says that people shouldn’t shy away from debate over such issues because they are afraid of being called anti-vet. “People shouldn’t support us just because we served. It’s not enough. They should support us because we know when we go back and transition, we become local mayors, or members of the Chamber of Commerce, or school board members. We shouldn’t revert to ‘support us, or you don’t support veterans,‘ ” says Rausch. “That’s bullshit.”

It’s possible that all the good work that vets, vets’ groups, and the VA have done to educate the public about veteran suicide, homelessness, PTSD, and other mental health challenges facing the military community has had an unintended consequence, perpetuated by the press and Hollywood. Because America doesn’t do nuance well, and likes to occupy the extreme ends of everything, every veteran must be damaged in some way if we keep hearing that some of them are.

During the first-ever commander-in-chief forum in September, Marine veteran Rachel Fredericks asked Republican now President-elect Donald Trump what he would do to prevent the 20 veterans a day from killing themselves. Trump began by incorrectly correcting her, citing an outdated statistic. But, more importantly, Fredericks believed the way he eventually answered the question fed into the stereotype of veterans as victims, suffering disproportionately from mental illness compared with the rest of the population. “He kept saying, ‘They need help, they need help,‘ ” she said in an interview with MSNBC after the forum. “I think everyone in America needs some kind of help, but yet again, we are going to stigmatize the veterans who are suffering from mental health diseases or with PTSD.”

Berger points out that PTSD is not unique to vets, though it’s often portrayed and perceived that way. Victims of sexual assault, car accidents, and natural disasters are just a few examples of other groups who experience and are susceptible to post-traumatic stress disorder. “There is sort of this association between mental illness and serving in the military that is totally unjustified, and yet we persist in looking at it that way,” says Berger, who serves as executive director of the Vietnam Veterans of America’s veterans health council.

Often in news reports involving violence or terrorism, the perpetrator’s veteran status is highlighted. This past summer during the spate of violence targeting police officers, the two shooters in Texas and Louisiana were veterans—a fact that vets’ advocates worried would further inflame the angry, crazed vet stereotype. Of the eight officers killed in the attacks, four were vets. “The truth is that veterans are much more likely to be the rescuer than the assailant,” Rieckhoff told The New York Times in a July 18 story. “But there is this lazy stereotype that we come back as damaged souls.”

Neither shooter had combat experience, nor was there any evidence that either suffered from PTSD as a result of military service, according to the article. Even so, “the image of the war-haunted, violent veteran has often eclipsed the quieter reality of the millions of veterans who have thrived back home in civilian life,” the report noted.

The Empowerment Movement

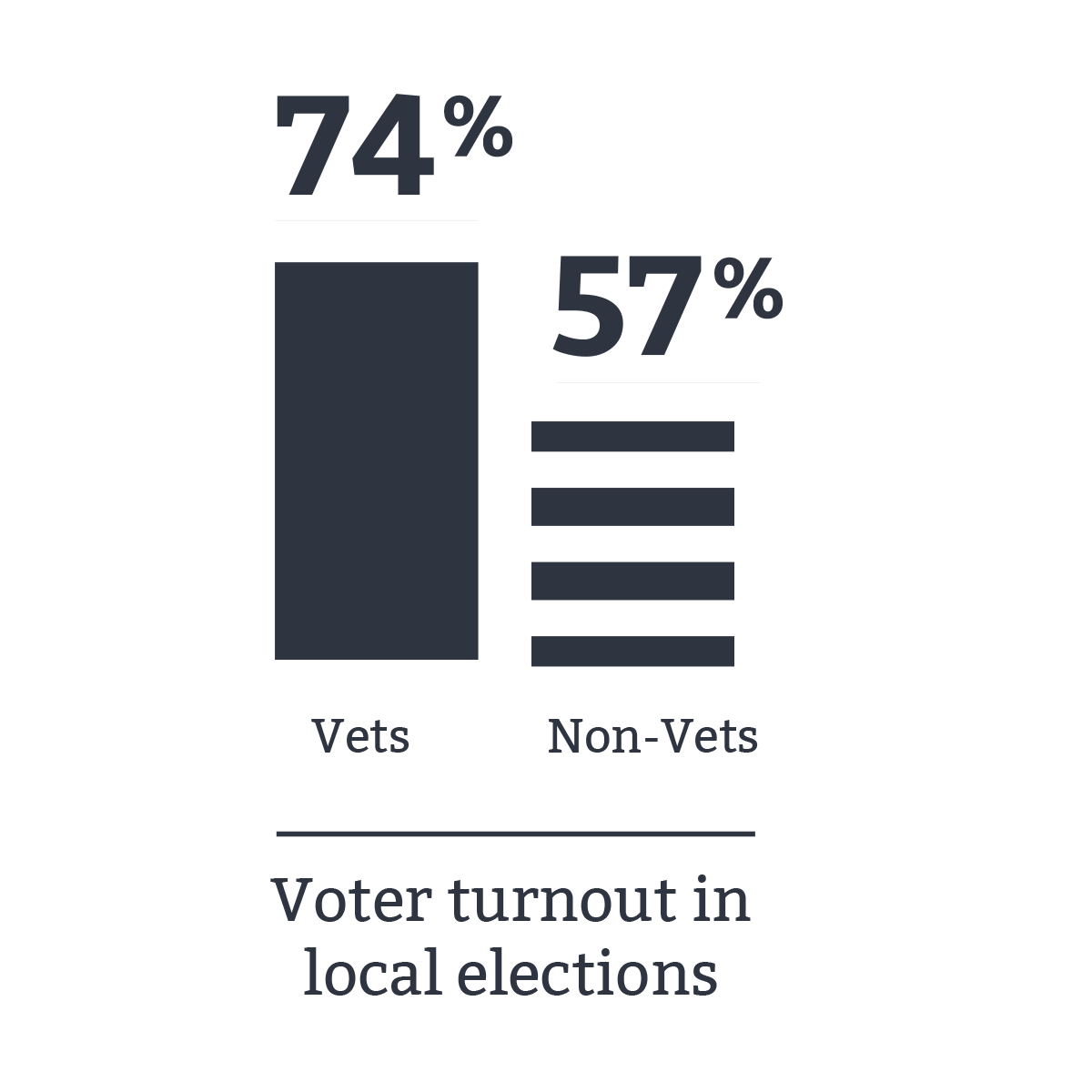

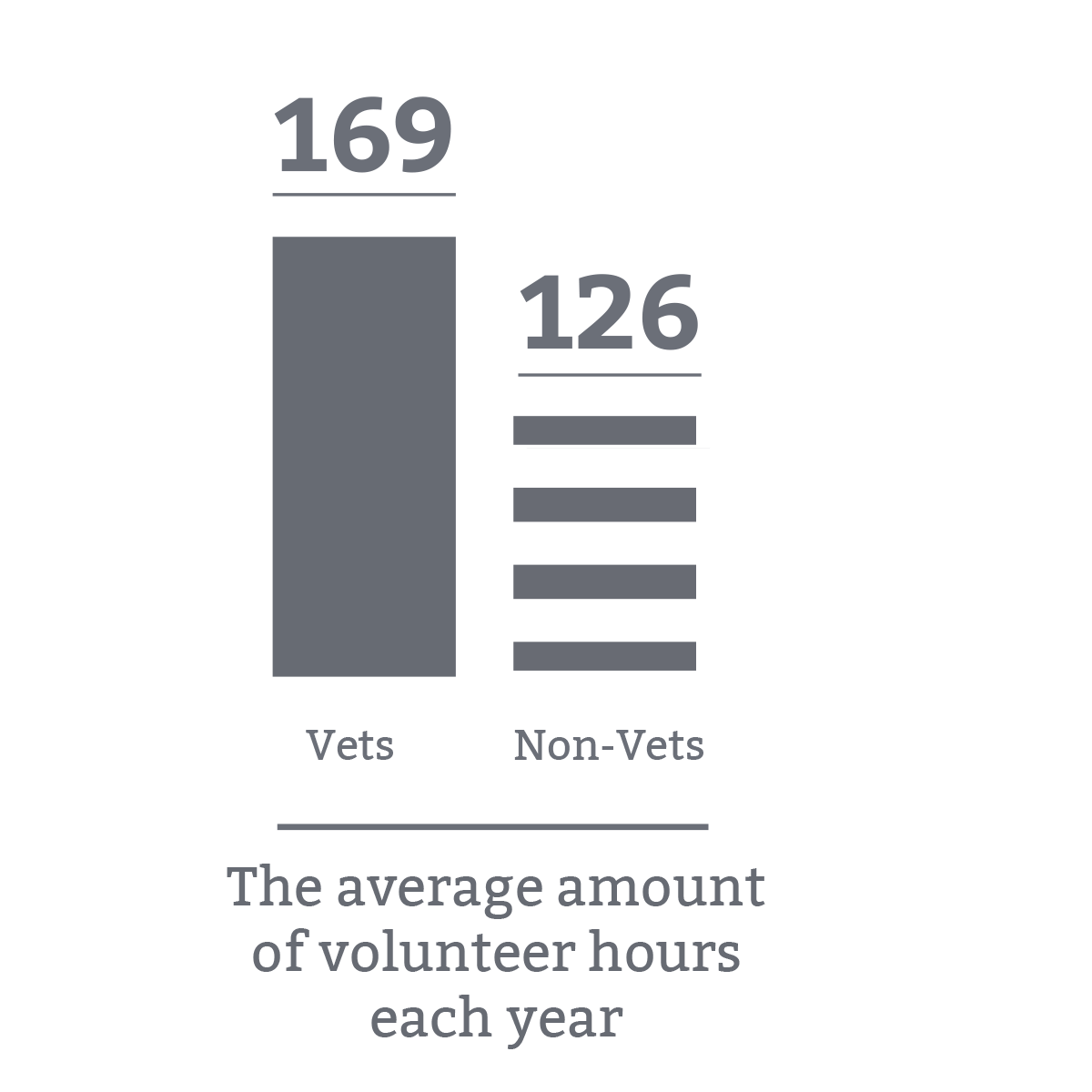

When it comes to measuring civic engagement, vets seems to be contributing more to the community than non-veterans, according to a September report based on government data. The 2016 Veterans Civic Health Index found that 74 percent of vets vote in local elections compared to 57 percent of non-vets, and volunteer an average of 169 hours per year—43 hours more than those who haven’t served in the military. Vets are also more likely to give to charity, contact public officials, attend public meetings and work with their neighbors to solve problems in their communities, concluded the study released by Got Your 6.

High levels of civic engagement among veterans put them in a strong position to effect positive change in communities and help tackle some of the country’s most pressing problems. For instance, many law enforcement officers have served in the military, and various leaders within the Black Lives Matter movement are veterans. “Our veterans are going to be the leaders in those communities to change what’s happening with race relations, the different concerns with our police and our citizens,” said Army veteran Janaia DeShields, vice president of veteran and military programs at Points of Light, during a September event unveiling the civic health index. “I believe that our veterans are going to be the ones that serve as the mediator, the facilitator, to help tie the two and bring the two together.”

Post-9/11 non-profit groups like Got Your 6, Team Rubicon, which deploys veterans to disasters worldwide to work alongside emergency responders, and The Mission Continues, aim to bring together vets and civilians, dispel stereotypes and perhaps, most importantly, empower vets to engage and lead in their communities. “Leadership is an inherent quality and trait that we learn in the military,” says Air Force veteran Lourdes Tiglao, a communications manager for Team Rubicon, who also spoke at the September Got Your 6 event. “I don’t think anyone can thrive in the military if you don’t at least learn that.” Vets often long for the camaraderie and the sense of purpose the military gave them, and many of these non-profit groups want to remind them that they can replicate those positive experiences as civilians in the community.

Vets from different generations also find support and empowerment from each other. “No one understands post-9/11 vets better than the Vietnam War generation does,” says Sherman Gillums Jr., executive director of the Paralyzed Veterans of America. Gillums is a 12-year Marine Corps vet who broke his neck in 2002 at Camp Pendleton when his vehicle rolled over. “There is a kinship there.” In fact, it was the Vietnam generation who fought to bring awareness to PTSD (it was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980) in addition to the horrors of Agent Orange. Each generation of veterans throughout history have helped attain benefits and public respect, battles that have benefited the next generation of warriors and military families.

A Vietnam veteran searches for the name of his fallen comrade on the Traveling Vietnam Memorial Wall during the Texas Military Forces Open House at Camp Mabry, Austin, Texas, April 21, 2012. The wall is a slightly smaller replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington D.C. (Photo by National Guard Spc. Praxedis Pineda)

When he returned to his hometown of Marengo, Ohio, after leaving the Army, Rausch said a friend’s father who fought in Vietnam recounted how he took off his military uniform and threw it in the trash before coming home after the war. “I can’t imagine that. I was in Baghdad for 17 months, and when I flew [back to the U.S.], there were people cheering me. I cried. I was so humbled and embarrassed, frankly, that these people were thanking me.” Rausch says that many of the post-9/11 veteran community’s successes are because they are “standing on the shoulders of the Vietnam generation” who had to “fight for respect, honor and integrity, and all these things that I think the post-9/11 veterans sometimes, not always, can take for granted.”

“Thank You for Your Service”

There is an awkward dance between veterans and non-veterans, the proverbial elephant in the room. The knowledge that 1 percent of the American population chooses to serve in the military, while the other 99 percent benefits from that decision creates a lot of superiority and inferiority complexes. And so, post-9/11, we’ve come up with a well-meaning phrase to assuage our collective civilian guilt every time we encounter a vet: “Thank you for your service.” It’s not a bad thing to say, but it can come across as hollow and lacking.

“The post-9/11 vets aren’t really that thrilled about being thanked for their service,” and then the person just walks away, says Mark Szymanski, director of public relations at Got Your 6. “They would much rather engage in conversation, have someone ask them what it was like to serve,” says Szymanski, who is not a veteran but grew up in a military family. But doesn’t that risk upsetting or offending the veteran? “When you think that person is a broken hero, it’s easy to say, ‘Ok, let me just do this, and get away from them really quickly because I don’t know how they will react.’” Szymanski’s point is that to learn, we need to take that chance, dive in, and listen. In other words, don’t take the easy way out.

We’ve got to educate ourselves because no one else—not Hollywood, the press, or the government—is going to do it for us.

“We’ve been at war since 9/11, for the longest period in American history,” says Berger. “Part of the problem stems from the fact that politicians didn’t communicate to the American people out there that war is really serious business. Instead, [it was] ‘We are going to send these young people to faraway places, and the rest of you can go shopping.’”