To understand how the Trump administration is delivering on a key campaign promise, consider the tip you left for the waiter the last time you dined out. You probably thought you were rewarding good service (or penalizing bad service, depending on how much you left). Beyond that, you probably didn’t think much about how that tip was actually handled and distributed. But the Trump team at the Labor Department has been thinking about it.

In late 2017, the administration proposed partially rescinding an Obama administration rule that would have ensured your tip actually went to the wait staff.

The move to give restaurant owners freedom to redistribute wait-staff tips to, say, cooks or busboys was launched with the same aura of certitude displayed by the Trump White House and its Office of Regulatory and Information Affairs—with promises of savings for business, greater fairness, and a transparent, evidence-driven process.

But something went awry in the execution.

Senior Labor officials at the Wage and Hour Division were uncomfortable with a cost-benefit analysis by department staff that showed workers could lose billions of dollars that would instead be controlled by restaurant owners. As reported

on Feb. 1 by Bloomberg BNA, the political appointees “ordered staff to revise the data methodology to lessen the expected impact,” according to inside sources. The political staff maintained that uncertainties in economic behavior made the analysis problematic.

The White House then approved the Dec. 5 publication of a proposal that omitted the quantitative data showing where the tip money would go.

In stepped Heidi Shierholz, a former Labor Wage and Hour staffer who is now senior economist and director of policy at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute. Her attempt to reconstruct the staff cost-benefit analysis concluded that tipped workers would lose $5.8 billion a year, that the take-home pay of back-of-the-house or other non-tipped workers would hardly change, and that employers in the aggregate would gain $5.8 billion a year.

The “justification for omitting a quantitative analysis is flawed and, given the fact that the department did indeed do an analysis, highly misleading,” she wrote in comments to Labor. “Obviously, the department was fully capable of quantifying key economic impacts of the rule in the presence of the type of uncertainty described.” She suggested the department had violated the Administrative Procedure Act.

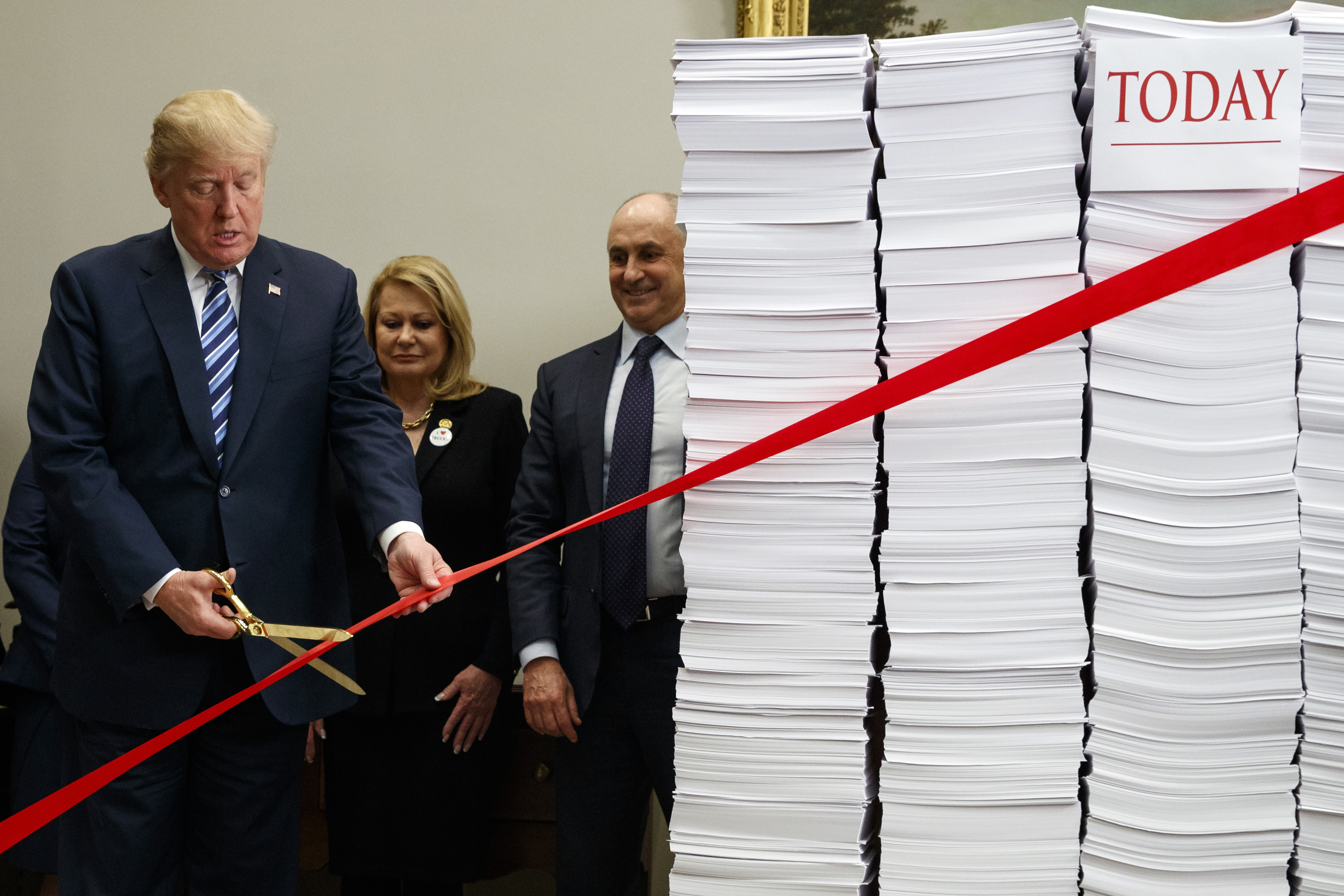

On March 27, 2017, President Trump signed four bills rolling back regulations he said were hurting the economy.

What it also showed, she told Government Executive, is that Trump officials at Labor were overruling the expertise of Wage and Hour career staff who, while not economists themselves for the most part, would contract out such a cost-benefit analysis and are themselves highly expert in “interfacing back and forth” in managing such a contract.

The White House intervention in Labor’s restaurant rule “was clearly done by the politicals and reflects a lack of respect for career staff,” said Sam Berger, a senior adviser for the Center for American Progress who held several policy jobs at the Office of Management and Budget. “They looked at the numbers, decided they didn’t like it and said take it out. It’s basically forcing the career staff to lie, and puts them in a terrible position.”

Neomi Rao, who leads the deregulatory push as administrator of Trump’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, declined to comment specifically on the analysis behind the tipping rule, suggesting the final version would provide the needed data.

But that seemed a far cry from her comments in a December briefing on Trump deregulatory accomplishments as published on the website RegInfo.gov. “So we’re working on . . . transparency,” she said, “and we continue to work with agencies on promoting the values of due process and fair notice.”

Neomi Rao, administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, says previous administrations overestimated the benefits of regulations, while underestimating the costs. (Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee)

Checks and Balances

Regulations are among the the stocks-in-trade of government—they are the tools through which the Environmental Protection Agency implements anti-pollution laws, the Interior Department enforces land-use provisions and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau restricts payday lenders. The chief debates over regulation center on the philosophical and ideological differences over government’s responsibilities versus free market rights.

For the Trump administration and many conservatives, it has become an article of faith that regulations are out of control and should be pared back, and there’s plenty of popular support for that view. A January Washington Post-ABC News Poll found that 44 percent of Americans thought “reduced federal regulation on businesses” was “a good thing,” compared with 42 percent who saw it as “bad thing.”

But to many regulatory professionals in and out of government, the Trump agenda raises questions of process.

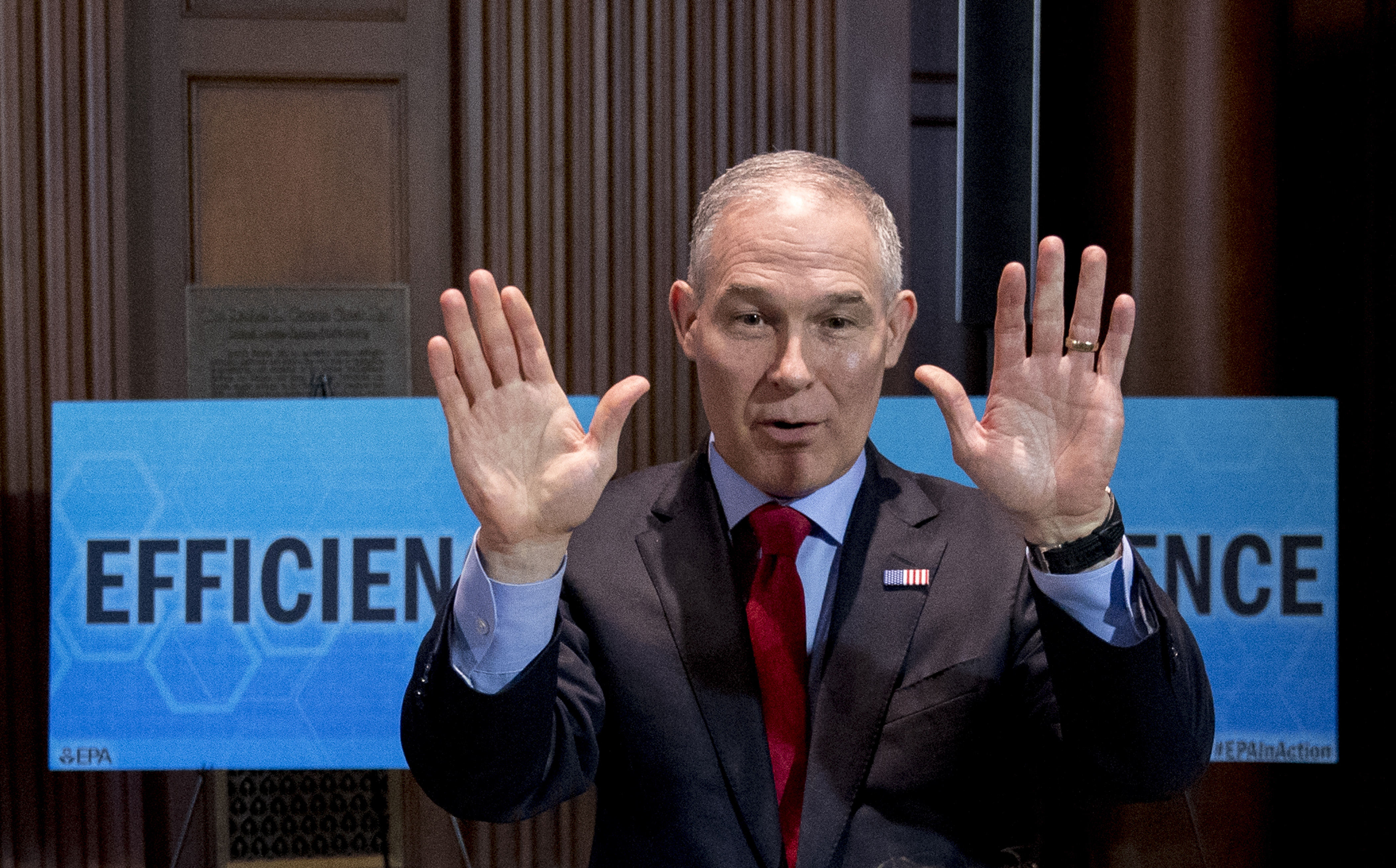

“EPA abruptly reverses a rule addressing hazardous air pollution following a single request from the [Environment and Public Works] committee chairman,” shouted a January press release from Sen. Tom Carper, D-Del., attacking both EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt and the chairman of the panel on which he is ranking member. “While citing no analysis of the public health impacts of this decision, Administrator Pruitt’s EPA has proactively allowed polluters to increase output of toxic air pollution.”

At EPA, as well as Interior, “decisions for the most part are made without consulting or seeking advice from long-time experts,” said Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. “At EPA, the decision gets made to repeal the clean water rule to go in a different direction. So they assemble the career staff, which is then directed by a political appointee without a paper trail,” he said.

“It took Pruitt’s people five days to rewrite a cost-benefit analysis that took more than two years to write and reach an opposite conclusion,” he added, referring to the Obama administration’s controversial Waters of the United States rule on protecting wetlands. “They reach a conclusion that wetlands have no value, none that is knowable” to delay the effective date of the rule.

Ruch also thinks EPA rulemakers know that this new approach is “legally vulnerable to a challenge as arbitrary and capricious.”

But the notion that an agency can foist opinions of politicians or industry lobbyists onto a regulatory agency of professionals sounds far-fetched to Susan Dudley, the director of The George Washington University’s Regulatory Studies Center who ran the White House regulatory office under President George W. Bush. “We have a government of checks and balances, and expertise is very valuable,” she said. “There’s no way they can make these decisions simply based on politics. I can’t think of an agency staffer who would say they want to get rid of a rule that provides enormous benefits to the public and put in a rule that does not.”

Yet career employees, despite their famous pride in serving under different administrations, are clearly steered by their agency’s political leadership. “I’m not sure expertise really matters much because what is happening now is that the Trump administration, through its appointees, is implementing executive orders,” said Peter Wallison, who holds the Arthur F. Burns Chair in Financial Market Studies at the American Enterprise Institute. “They are sending signals to the business community that there would be much less regulation, which is a tremendous force in business for being first out of the gate when a major change is happening,” he said.

“It does take some expertise when you’re in the agencies to know how to pull back and stop a regulation in process. And yes, expertise is necessary to understand what Congress wanted the agency to do and to faithfully execute the laws,” Wallison added. “But they then have to consider that the Trump administration and the person now heading the agency wants them to meet their statutory regulations and not overregulate.”

Rao herself professes “very strong respect for the expertise of career staff,” as she told an audience at the Brookings Institution in February. Many of them are motivated by “competition between agencies,” she said, in not wanting to be last in paring back rules that “are no longer helping the American people,”

Decisions for the most part are made without consulting or seeking advice from long-time experts.

Jeff Ruch,executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility

Trump’s New Approach

Republicans for decades have embraced deregulation as a way to boost the economy and reduce government’s role in the affairs of business. But the Trump administration has broken new ground. In January 2017, the president signed executive order 13771, which required that for every new regulation added, two regulations had to be cut, marking the first time such a numerical goal has been attempted.

A subsequent order required designation of “regulatory reform officers” at each agency, plus regulatory task forces whose outside memberships were not publicly disclosed.

OMB’s new regulatory budget, which requires each agency to cap the cost of its rules, is unprecedented. OIRA round-ups now characterize actions as to whether they’re regulatory or deregulatory.

Finally, Congress for the first time has used the 1996 Congressional Review Act to move Trump’s agenda to cancel previous administration rules within 60 legislative days.

“We’ve never had this before, having people in agencies whose job it is to find existing regulations that could be improved or rescinded—it’s more significant than I initially thought,” said former OIRA chief Dudley. Though the concept of a regulatory lookback can be traced to the Carter administration, “before, the incentives weren’t there, and now we are seeing a slower growth in new regulations in the unified agenda.”

Sally Katzen, who ran OIRA under the Clinton administration, said the Trump transition arguably created the widest breach between political appointees and the civil servants. Though it differs by agency, “there were a number of anecdotes that the confirmed political appointees and their aides weren’t talking to the career staff. They would ask staff for information, which was dutifully delivered, but then career staff had no clue what the consideration or disposition was,” she said.

“Top it off with the fact that many of the nominees for political appointments in the agencies were clear about their disagreements not just with what the agency had done under Obama, but with its basic mission,” she added. One example is Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, “whose view of her mandate is very different” even from the Bush and Reagan years.

Katzen, who is now a New York University law professor, said civil servants understand that different administrations have different priorities and that elections matter. OMB civil servants, for example, “work diligently until noon on Jan. 20 for the outgoing president and then work just as diligently for the incoming president beginning at 12:01 that day.” Yet many Trump appointees “have a deep distrust of the civil service, and therefore are not getting the benefit of their experience and expertise.”

Neil Eisner, former general counsel for regulation and enforcement at the Transportation Department, told Government Executive his contacts in government say many of the expert career staff don’t know what’s going on. “They say they’re not doing much new, mostly spending time reviewing existing rulings to see which ones get revised or revoked.”

But even if the agency is planning to revoke a rule, Eisner, who still attends meetings at the Administrative Conference of the United States, added, “You still have an obligation to do an analysis, and it still takes a rulemaking.”

Reeve Bull, the research director of the conference (an independent federal agency that seeks to improve the rulemaking process through consensus-driven applied research) told an audience at The George Washington University last October that the Trump deregulation push is also “a resource issue.” The agencies “have been tasked with regulatory reform but haven’t been given the manpower,” he said.

Bull said it is “understandable” that staff would pay more attention to prospective regulations than to lookbacks. Going back to the Carter administration, “it has been very difficult to get the incentives in place.” And because of the asymmetrical nature of technical understanding in the administrative law realm, “only agencies themselves and perhaps to some extent the regulated parties have the necessary information to understand the complexity of rules to really delve into the details necessary to do a good job.”

Al McGartland, who directs the EPA’s National Center for Environmental Economics, told the same conference that the Trump approach requires a “different sequencing of the steps, a two-step process.” It has effectively “doubled the workload.”

EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt has been aggressive in his efforts to roll back environmental protections implemented during the Obama administration. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik))

Weighing Costs and Benefits

Under the previous administration, Rao has said, regulatory analysts “tended to overstate the benefits and understate the costs.” The Trump goal is analysis that is “more rigorous.”

The well-established rulemaking exercise of pitting costs against benefits “is not an answer, but a process,” said Ted Gayer, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution. “The hard-core economists who analyze benefits and costs sometimes lose friends on the right, and sometimes on the left.” They clash with lawyers who represent interests, he said, a tendency on the rise in the Trump era. But Gayer told Government Executive he hasn’t seen evidence that “one side is being more marginalized than in previous administrations.”

Yet in the past, those in the regulatory field “agreed on a framework . . . that was methodically intense, transparent, and nonpartisan,” he added. “In the world we live in now, the reaction to everything is seen as an instrument of one side or the other.”

What is subjective about cost-benefit analysis, Gayer said, are the assumptions, projected psychological and natural behaviors, which are subject to OMB guidance last updated in 2003. In climate change, for example, a rulemaker would have to apply what is called a “discount rate” and determine whether to measure effects of carbon emissions globally—as the Obama administration did—or domestically only, which is the Trump approach.

“The question is how much cost should we incur today to reduce climate change, when the benefits come basically 200 years from now,” Gayer said. “There’s a lot of value judgments that can legitimately sway the numbers drastically.”

Katzen expressed concern that in Trump executive order 13771, the word “costs” appears 17 times, and the word “benefits” not once (though Rao herself mentions benefits, she noted). “I’m worried the benefits side will get short-shrift. I hope I’m wrong.”

Berger of the Center for American Progress expressed more alarm. “The environmental rules, under the same circumstances, provide billions in net benefits, but then they get reexamined and suddenly there are billions in costs,” he said, acknowledging cost-benefit analysis often produces a range.

He accused OMB, his former agency now run by Mick Mulvaney, of making up costs and benefits numbers” even though the majority of staff are career. “You have that sort of lack of respect for staff and truth coming from OMB, which prides itself on nonpartisan unvarnished facts, so policymakers can make the most informed decisions. It’s demoralizing and embarrassing to the office.”

Impact on the Future

OIRA chief Rao promises new reviews of what is often derisively called “regulatory dark matter,” or agency-generated guidance, FAQs and information collecting she says can function as a “back door to imposing more regulation.” Such supplementary documents, she said, unfairly exclude the public and violate due process.

Republicans in Congress are also seeking to rein in guidance, as well as pass the Regulatory Accountability Act that would formalize regulatory review.

Even more ambitious is Rao’s plan to reinvigorate a dormant conservative plan to place under OMB’s management the rules issued by the independent regulatory agencies—the Federal Communications Commission, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, for example.

That centralization, she said, might even include the Internal Revenue Service, which since the early 1980s has been given authority to release its own tax guidance without OMB’s review.

As an example of its independence, FERC in January rejected a proposal by Energy Secretary Rick Perry to ease rules on the coal and the nuclear industries to protect the energy grid, and the staff of the SEC recently issued a report contradicting the White House's position on the negative effects of banking regulations.

The idea of bringing independent agency regulations under the purview of OIRA has been discussed since the Reagan administration, Katzen said, and was considered and rejected during her tenure with Clinton. “It’s a political matter, and the independent regulatory agencies are the children of Congress.”

The FCC’s recent creation of a new office of economics and analysis to pull all the economic and statistical analysts into a single unit could be important, said Dudley, who emphasized the importance of transparency in the regulatory process. “When the government takes regulatory action, there’s always a risk that the parties with the most to gain or lose can influence the government at the expense of average consumers,” she said. “Hence the best response for situations where decisions must be made collectively, she added, is to make sure we have best information both on the intended consequences and what goes wrong.”

The Trump deregulation agenda will depend upon career agency experts. “Under Obama, there were more than 3,000 new regulations,” Wallison said. “If you’re operating a business, you have no idea what’s going to come down on you from the continuum of agencies operating under broad mandate,” he said. “Where it stops along that continuum is in part a policy question, in part a legal question, and in part a political question. It does take a lot of intellectual power and thought by people in government in various agencies to understand where to draw the line and comply with the desire of the Trump administration for less regulation. Without expertise in agencies of where to assess those things,” he added, “the whole thing wouldn’t work.”

But there are signs of resistance among career staff, said Ruch of the environmental employees group. He points to fallout from sudden shifts in policy that don’t appear based on science. Elizabeth “Betsy” Southerland last August resigned in protest from EPA as director of the Office of Science and Technology in the Office of Water. And the office with the biggest exodus of EPA staffers taking buyouts is the Office of Research Development, he said. “A lot of specialists we talk to say that if they could only get in a room with Scott Pruitt, they could convince him, because he is smart,” Ruch said. “But they can’t get in the room. Even during minor briefings, he looks at his watch, with no meaningful interaction.”

But the Trump approach will make its mark. In the past, Dudley said, “There were no penalties for not looking back,” and without a lookback, the consequences are that agencies “simply stay in place.” Before Trump’s executive order 13771, the “incentive for staff was ‘I see a problem I can solve, what’s next?’ ” Now, she said, the “incentive is more to ask, ‘Did my past solution actually work?’ ”

Charles S. Clark joined Government Executive in the fall of 2009. He has been on staff at The Washington Post, Congressional Quarterly, National Journal, Time-Life Books, Tax Analysts, the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges, and the National Center on Education and the Economy. He has written or edited online news, daily news stories, long features, wire copy, magazines, books and organizational media strategies.