The Ease of the Postal Service Makes It a Vector for Violence

A short history of how the mail has been exploited for terror.

If the Postal Service did not already exist, if its reach had not grown organically as the United States grew, then the idea of building one from scratch today might seem absurd. How preposterous it is that anyone can scrawl an address on an envelope and expect it to arrive days later at a specific address—be it inside a Manhattan high-rise or at the end of a dusty country road? How wonderful that it does.

But these same features—the ease and relative anonymity of sending, the specificity of receiving—have also been exploited to turn the postal service into a vector for violence.

The latest example may be the package bombs that have killed two people and injured two others in Austin, Texas. The packages in these cases do not appear to have been delivered by the U.S. Postal Service or services like UPS and FedEx, and it is unclear how individually targeted they were. But the boxes were left intentionally on the doorstep, masquerading as a package with an intended recipient—perhaps a surprise gift or forgotten Amazon order or, as the neighbor of one injured woman suggested, a routine delivery of medicine.

The victims in Austin have all been African American or Hispanic, so police have not ruled out the possibility of a hate crime. Whatever the motivation, package bombs taint the trusted network of mail delivery, injecting fear into the routine act of opening mail.

The idea has a long history. One of the first recorded deliveries of a package bomb comes from the diary of the Danish historian Bolle Willum Luxdorph. In January 1764, a man named Poulsen at Børglum Abbey received a package. “When he opens it, therein is to be found gunpowder and a firelock which sets fire unto it, so he became very injured,” writes Luxdorph. Weeks later, Poulsen received a vague threat suggesting the next package would contain more gunpowder. The motivations and sender are unknown.

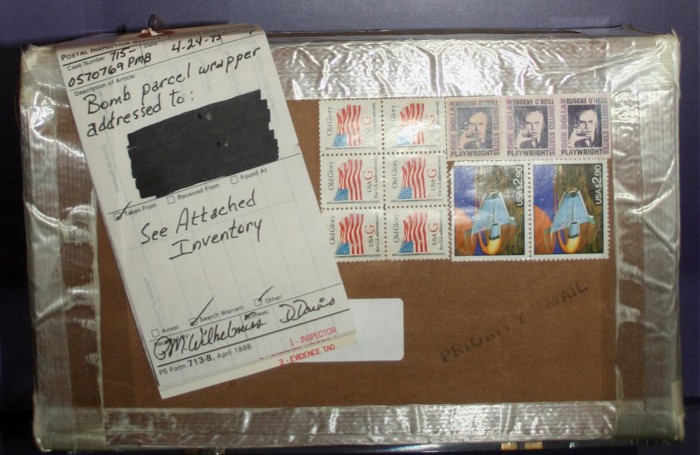

A letter bomb on display at the National Postal Museum (Wikipedia)

Beginning in the 20th century—as the mail-delivery system became even more codified and expansive—letter bombs became a tool of political terrorism. In the 1940s, an extremist Zionist group sent letter bombs to senior British officials and to President Harry S. Truman. The bombs sent to the White House came in “cream-colored enveloped” containing “powdered gelignite, a pencil battery and a detonator rigged to explode the gelignite when the envelope was opened,” wrote Truman’s daughter in a biography of the president. Targets of letter bombs have included: the International Monetary Fund, embassies, John D. Rockefeller, judges, journalists, an anti-Apartheid activist, local police, and prime ministers.

And then there is, of course, the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski. Beginning in the 1970s, Kaczynski targeted universities and airlines, injuring 23 people and killing three. After a threat mailed to the San Francisco Chronicle in June 1995, the USPS scrambled to come up with a plan to inspect all air mail packages out of California. For six days, USPS did not accept packages or letters bigger than 12 ounces. The threat, Kaczynski later admitted through an anonymous letter to the New York Times, was a prank. He had played the system against itself—delivering anonymous taunts through the mail and disrupting the very mail-delivery system.

The USPS is well aware of the ways in which a postal service can be abused. Its law-enforcement arm, the Postal Inspection Service, responds to thousands of suspicious packages a year, and it played a role in the capture of the Unabomber.

The physical dangers carried in mail are not restricted to bombs. In 2001, envelopes containing anthrax spores began arriving at media companies and Senate offices. Suddenly, in a country already on edge after 9/11, all unknown white powders became suspect. It also set off a trend of fake attacks, in which envelopes arrived stuffed with anything from talcum powder to baking soda. Even if the anthrax was fake, the mail came with an implicit threat: a physical embodiment of the taunt “I know where you live.” If you cannot feel safe while mindlessly opening mail, can you feel safe at all?

In Austin this week, neighbors told reporters they were wary of packages now, even expected ones. A grandfather pointed to his grandson: “This one here is waiting on some tennis shoes,” he told the New York Times. “I told my daughter I’m going to throw them in the middle of the yard to make sure they’re safe.”