Is the Federal Government Ready for AI?

A survey-based analysis of feds' AI investment, readiness, and capabilities.

The United States has been competing with adversaries and working with allies on advancing artificial intelligence (AI) in defense for years. Leaders in research and development (R&D) such as DARPA and its intelligence community counterpart, IARPA, have been at the forefront of developing the next generation of AI tools focused on turning computers into "problem-solving partners."1

Building on the success of AI in national security applications, government organizations are exploring other opportunities for adopting the technology. Early efforts to introduce AI in citizen-facing Web tools (e.g., chat bots) and various forms of electronic document processing by federal agencies were the foundation for testing early pilot programs.2,3 Other government agencies followed suit, with initial indicators now pointing to a much larger role for AI in managing forms and documents as well as unstructured forms of data.4

AI proponents achieved a major victory with the signing of the American AI Initiative, billed by the Trump White House as "a concerted effort to promote and protect national AI technology and innovation" and the publication of a robust, public-facing program of AI development and education, hosted on a catch-all site: https://www.whitehouse.gov/ai/.5

Key Agencies as identified by the White House on https://www.whitehouse.gov/ai/ai-american-innovation/. Accessed March 20, 2019.

Overview

Executive Summary

- AI is seen as a mission critical priority, and has featured in budgets and strategic documents across the public sector. However, many federal government employees see their organizations as remaining in the exploratory phase of AI implementation or even earlier in the process.

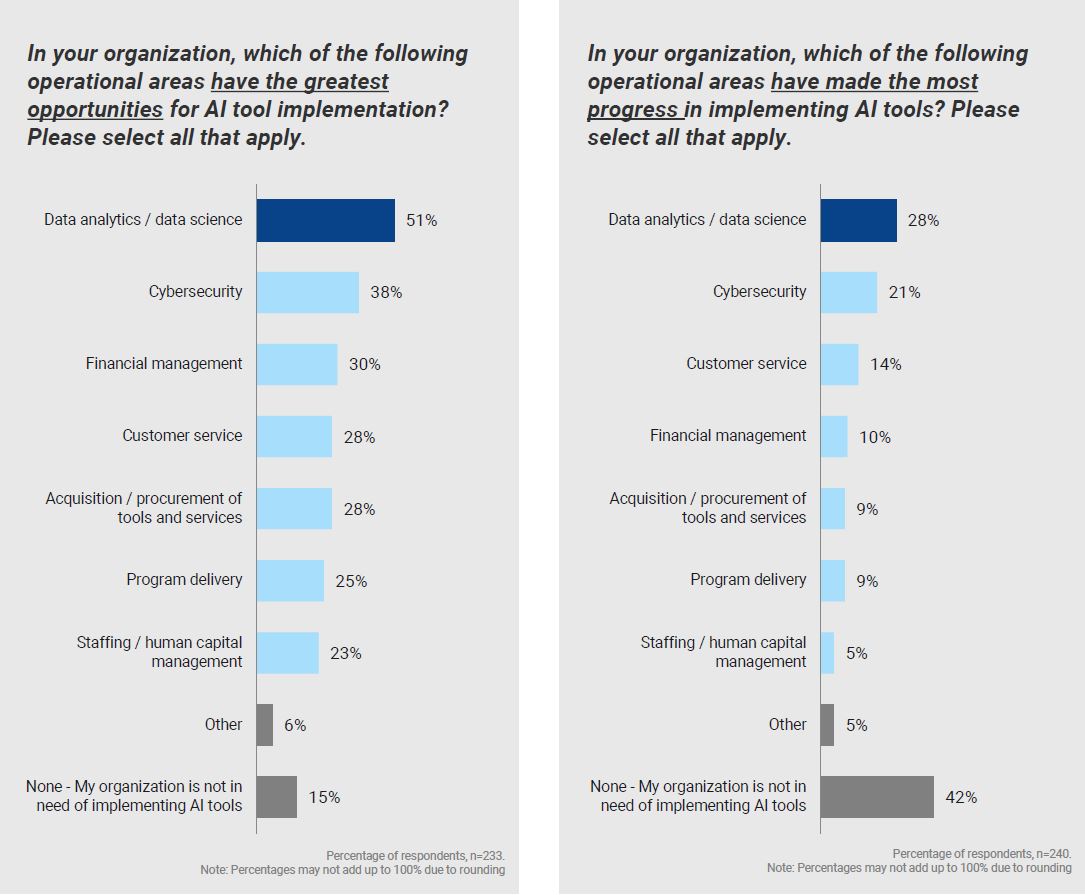

- Respondents identify data analytics / data science, cybersecurity, and financial management as the biggest priorities for AI. They also indicate that the most progress has been made in these areas, though progress trails aspirational goals.

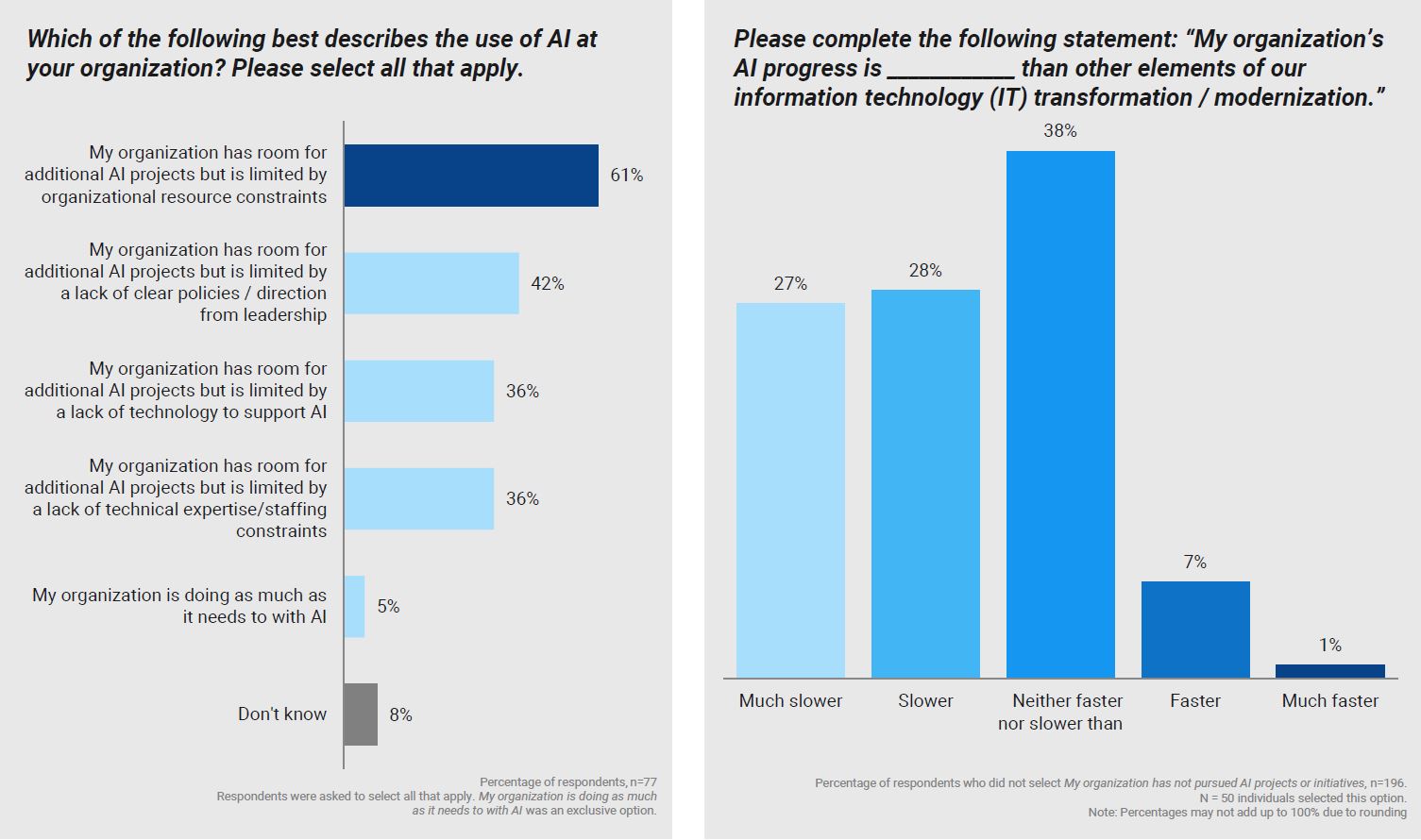

- Elaborating on the perceived misalignment between AI-ready teams, survey respondents also identify the biggest limitations in their organization's AI implementation: organizational resource constraints (61% of respondents), a lack of clear policies / direction from leadership (42%), and a lack of technology supporting AI (36%). Other barriers include budget / financial constraints, a lack of conceptual understanding about AI, and the cost of managing existing/legacy infrastructure.

- Federal employees — including management staff as well as technical leaders — are ready for AI, but they see the technology as a strategic priority that needs to be guided at the highest levels of government rather than solely at the feet of practitioners.

Methodology

In February and March 2019, Government Business Council (GBC) surveyed 668 decision makers in the federal government, including leaders in civilian and military agencies. Using an online survey, GBC polled these individuals on their organization's AI priorities, challenges, and perspectives.

Key Findings

1. The Lay of the Land

Across several studies, GBC has seen a growth in the amenability of federal employees towards civilian AI applications — in a study we conducted in November 2018, significant shares of federal government respondents reported using or planning to use advanced analytics (43%), machine learning (30%), and even natural language processing (18%).6

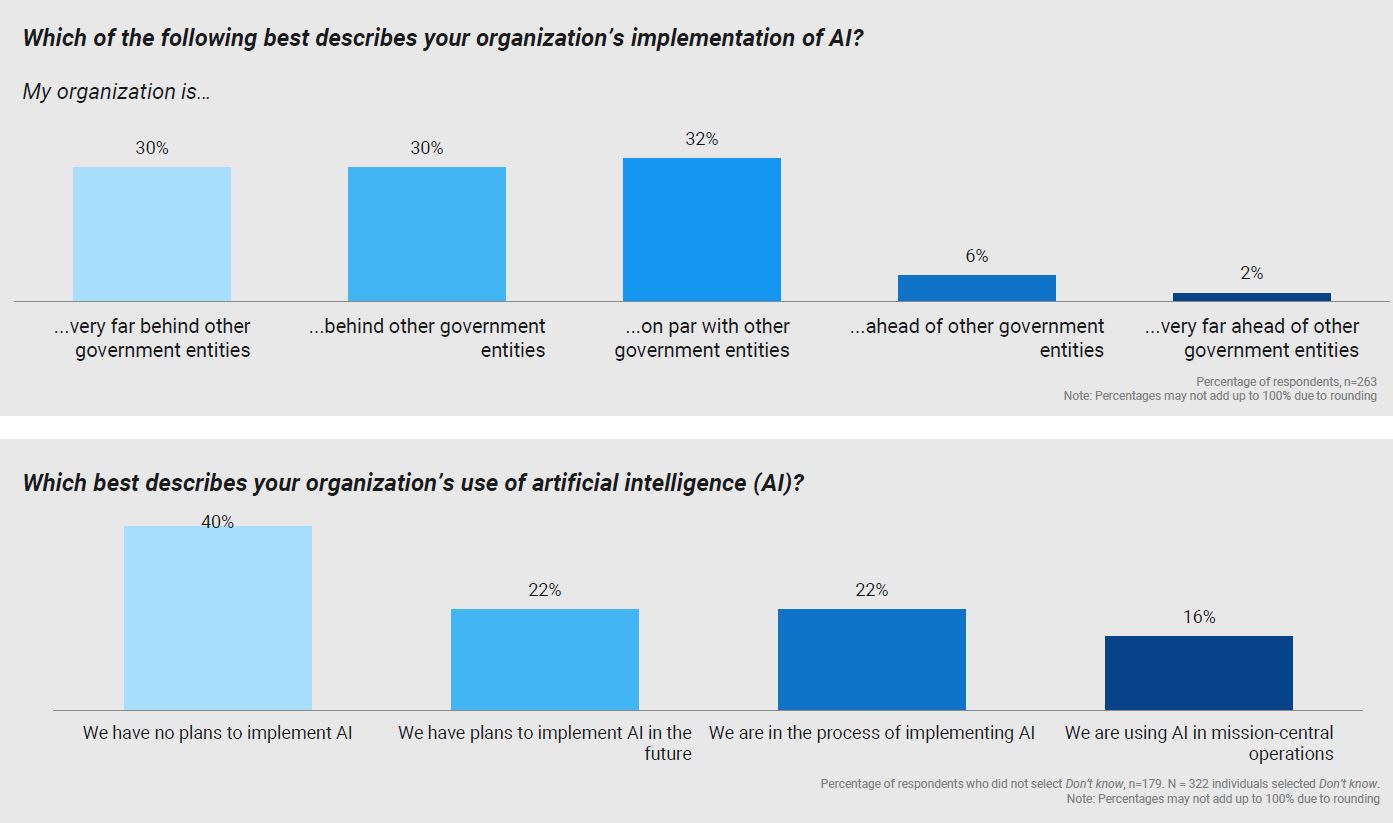

Still, according to the survey fielded in February-March 2019, implementation appears to be a work in progess at best. When asked about their organization's use of AI, a plurality of federal employees indicated that they have no plans to implement AI. Comparably small shares of respondents indicated that they are using AI in mission-central operations (16%) or that their organization is in the process of implementing AI (22%).

Respondents are similarly skeptical about the pace of their organization in relation to other public sector organizations. When polled, 60% of the federal workforce indicated that they saw their organization as behind or very behind other government entities in AI implementation. By comparison, just 8% of those surveyed believed they were ahead or very far ahead of their government peers — early evidence of an AI confidence gap.

2. Understanding Capacity

GBC research further uncovered the current operating level of federal organization's AI capacities. Two-fifths (40%) of those polled — the large plurality of the survey sample — indicated that AI was unlikely to reach mission critical capacity within the next two years.

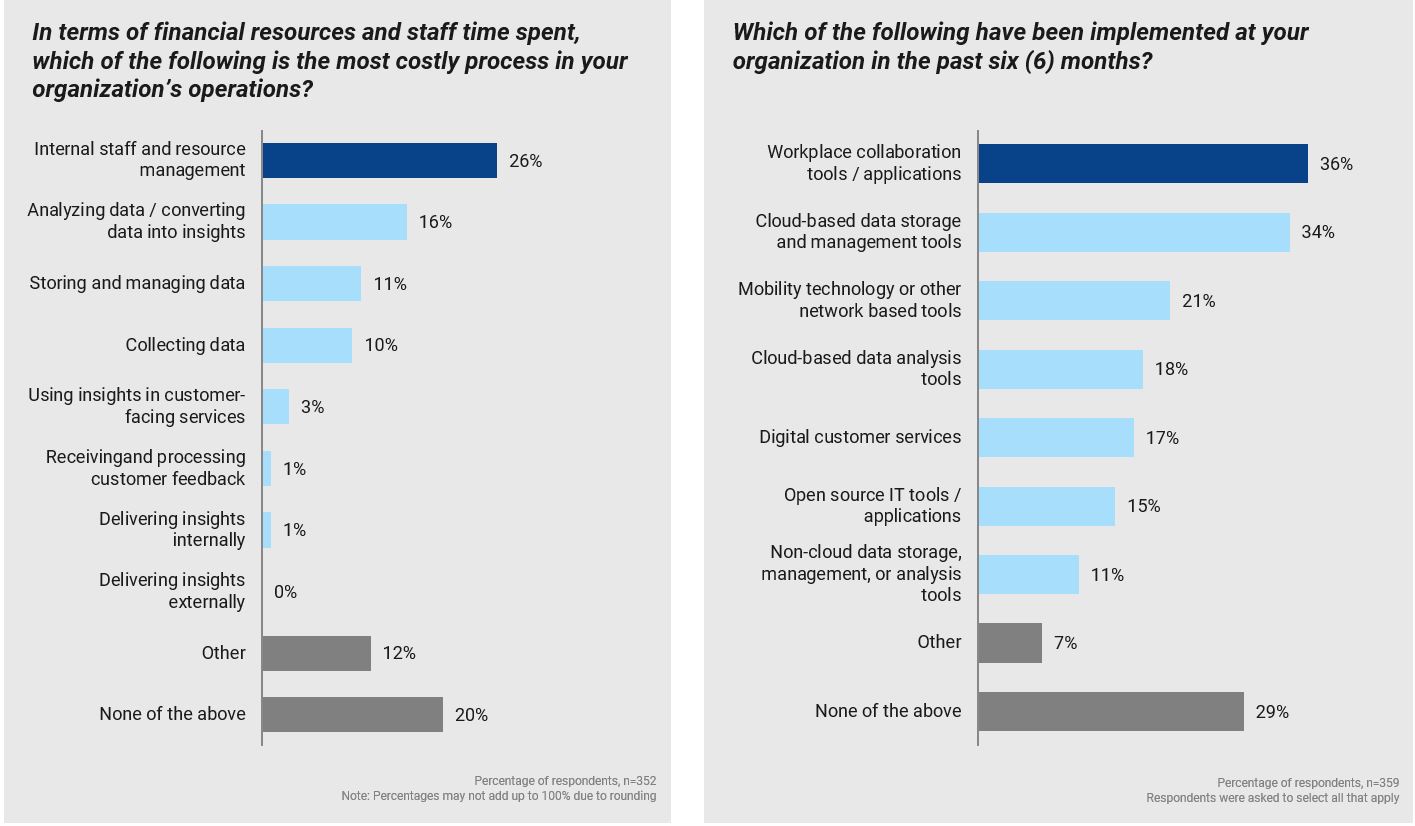

Digging deeper, GBC found that the biggest black hole for organizational resources consists of internal staff and resource management — more than one-quarter (26%) of respondents selected this option, compared to relatively smaller shares for analyzing data / converting data into insights (16%), storing and managing data (11%) , and collecting data (10%).

These insights show alignment between staff-defined priorities (e.g., increasing internal efficency and optimizing data analysis) and IT tool adoption. More than one-third of respondents specified that workplace collboration tools / applications (36%) and cloud-based data storage and management tools (34%) have been put into practice at their organization, while an additional 18% also cite cloud-based data analysis tools. Still, there appears to be at least some lag between stated goals and what has been achieved on the ground.

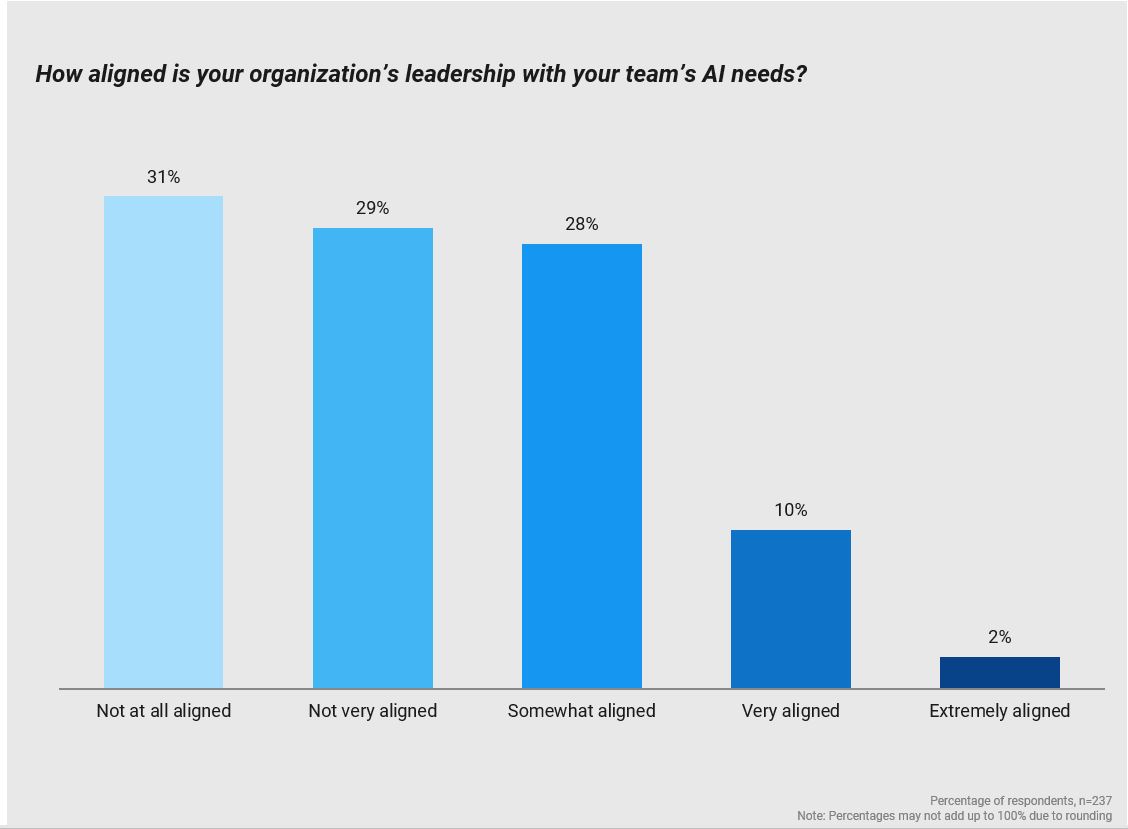

A large share of survey respondents report misalignment between individual teams and organizational management at the agency or department level. While a sizable share (40%) of those surveyed indicated that the two groups were at least somewhat aligned at their organization, the majority (60%) believe their organization's leadership is either not at all aligned or not very aligned with their team's AI needs.

For AI to succeed, there will need to be clear and effective channels between AI end-users and the individuals setting broader goals, strategies, and policies.

3. Trial and Error

Along with related and subsidiary technologies (e.g., cognitive computing and machine learning), AI represents one of the truly uncharted areas of information technology. While there are opportunities for re-tooling and leveraging past frameworks for technological implementation, aspects of the AI introduction process will be at least somewhat experimental.

But that doesn't mean the public sector is going in blind. Following the principles of agile development and DevOps, and increasingly looking to similar data-centric strategies like DataOps, federal agencies are accepting the uncertain nature of IT exploration and are making necessary adjustments to their operational practices.

Brought to you by

At this ‘bleeding edge’ moment of AI evolution, the full potential is still coming into view. One thing that is already clear, however, is the need for robust infrastructure to support AI efforts. This includes the data center itself, which will be required to have storage capacity for massive data sets and organized data warehousing. To achieve this, government agencies will have to elevate the storage, networking, and compute capabilities of their ecosystems.

Additionally, any AI-capable data infrastructure is going to need the compute and processing power that can support real-time analytics and produce. The most effectively engineered solution is only as effective as its benefit at the point of implementation. Harnessing AI-derived insights at the pace required by mission-centric decisions will hinge on achieving requisite compute and processing levels.

Another key component in the recipe for AI success is the networking factor. Operationalization of AI requires near-real-time flow of data from multiple sources from edge to the data center; without integrating these sources, the power of AI can be significantly diminished. Towards that end, federal government decision makers have an opportunity to work with leading industry partners to build out underlying technical tools ― indeed, many already do. By leveraging as-a-service arrangements, government can ensure that AI is financially attainable by enabling modernization and adoption of AI-ready infrastructure in a cost-effective business model.

There is a large degree of alignment between the greatest public sector AI opportunities (e.g., data analytics / data science, cybersecurity, and customer serivce) and the applications most frequently identified as success areas. Despite notable share of respondents reporting progress in these areas, 42% indicate that their organization is not in need of implementing AI or has not successfully made progress in any of the listed AI applications.

Indeed, while confirming some ongoing assumptions about AI — namely, that the technology carries special promise in data applications as well as cyber defense — survey respondents also showed the capacity for AI to improve more mission critical functions (e.g., financial management and customer service), demonstrating potential new areas for cost savings and optimization.

Federal government respondents were equally helpful in illuminating the nuances of their agency's experience with AI. Most immediate was evidence that there is a real need for AI in the federal government — it is also clear that this need is currently underserved.

When polled, just 5% of survey participants indicated that their organization is doing as much as it needs to with AI. By contrast, more than one-third of respondents stated that their organization has room for additional AI projects but is hindered by a lack of clear policies / direction from leadership, a lack of technology to support IT, or a lack of technical expertise / staffing constraints (42%, 36%, and 36%, respectively). More than three-fifths (61%) selected the most frequently cited barrier to AI implementation: organizational resource constraints.

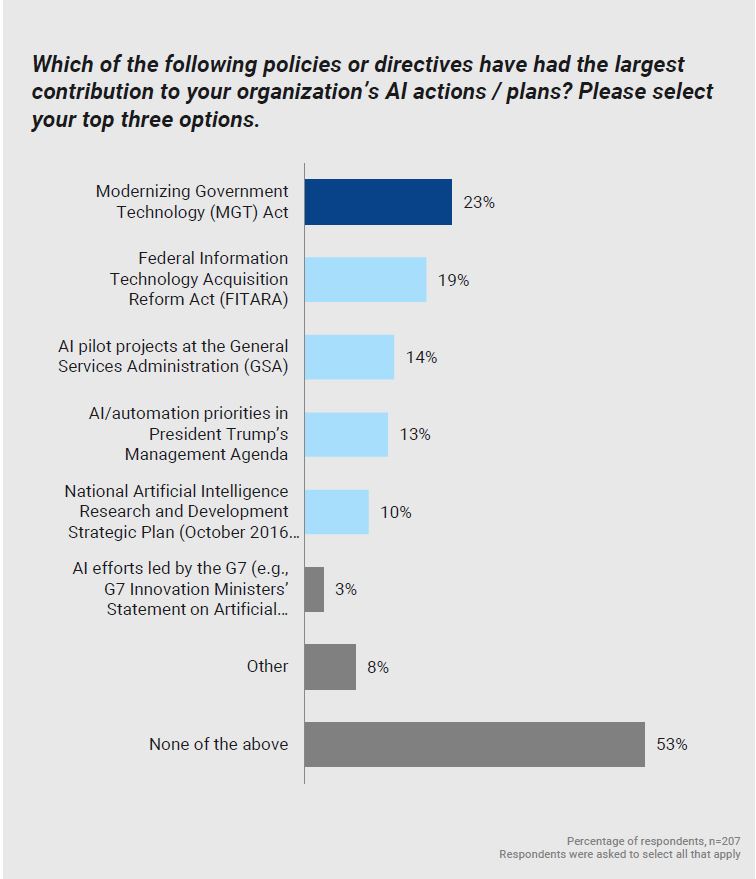

One lens for analyzing these experiences is the promulgation of policies and initiatives at various levels of government. When asked to select which of such directives have had the largest contributions to their organization's AI actions and plans, nearly one-quarter (23%) of respondents indicated the Modernizing Government Technology (MGT) Act; just 19% and 14% selected the Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) and GSA-led AI pilot projects, respectively.

More than half of those polled (53%) stated that their organization is not leveraging any of the above policies or directives, a share that may be responsive to the recent rollout of government-wide AI resources such as "Artificial Intelligence for the American People" and the President's executive orders on AI.

4. Navigating the Adoption Trail

By drawing lessons from the ongoing work of public sector organizations, other federal and defense partners have an opportunity to approach AI implementation through more systematic means.

This educational process is especially prudent in light of findings from GBC research into the topic. When asked about their organization's experience with AI implementation, one quarter (25%) of those surveyed indicated that the process has been more or much more challenging than expected. Only 2% of respondents believe the process has been less or much less challenging.

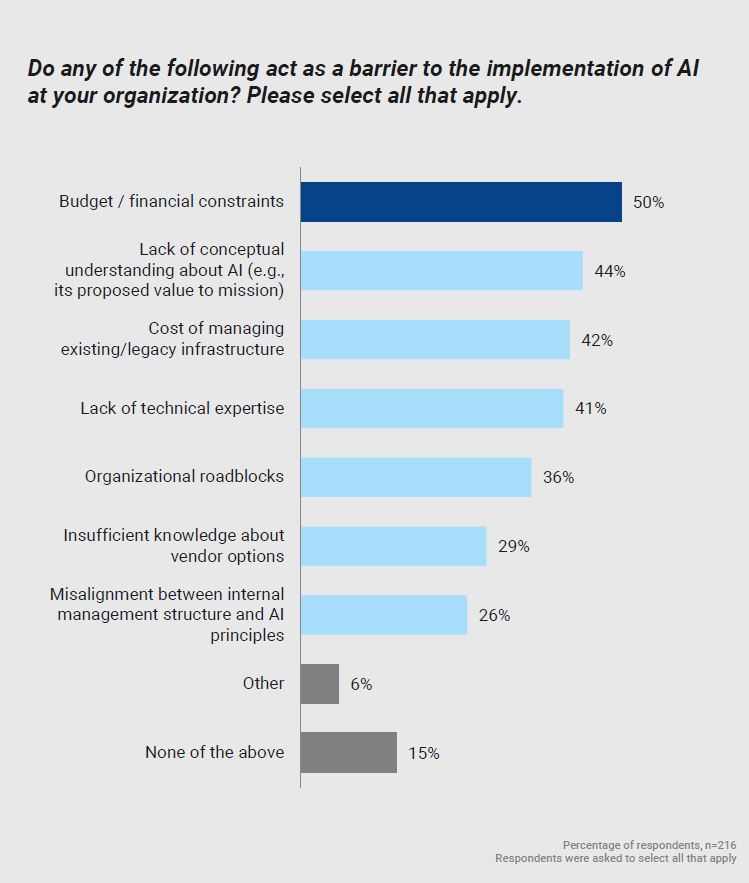

When asked to shed light on the barriers at their particular organization, half (50%) of respondents identified budget / financial constraints — more than two-fifths also selected a lack of conceptual understanding about AI (44%), the cost of managing existing legacy infrastructure (42%), and a lack of technical expertise (41%).

Although other barriers were selected with some frequency (e.g., more than one-third, 36%, of those surveyed identified organizational roadblocks), these four factors are indicative of the biggest hurdles between the AI status quo and the ultimate AI goals identified by federal government organizations.

However, there are potential opportunities for direct and multi-faceted melioration of these obstacles. By continuing to build on existing efforts to build public sector AI budgets and technical expertise, and by encouraging government agencies to take advantage of resources aimed to buttress inherently risky adoption processes, the White House and other bodies can foster a spirit of entrepreneurship in public sector AI.

Indeed, recent reporting and analysis indicates that the execution of many federal AI programs is still largely dependent on particular individuals or on very specific technical teams, and that this responsibility is not distributed throughout agencies and organizations.7 But the principles of cloud adoption, cyber security enhancement, and other technological modernization efforts point to the necessity of an integrated, strategic, and elevated approach — a notion echoed by the GBC survey.

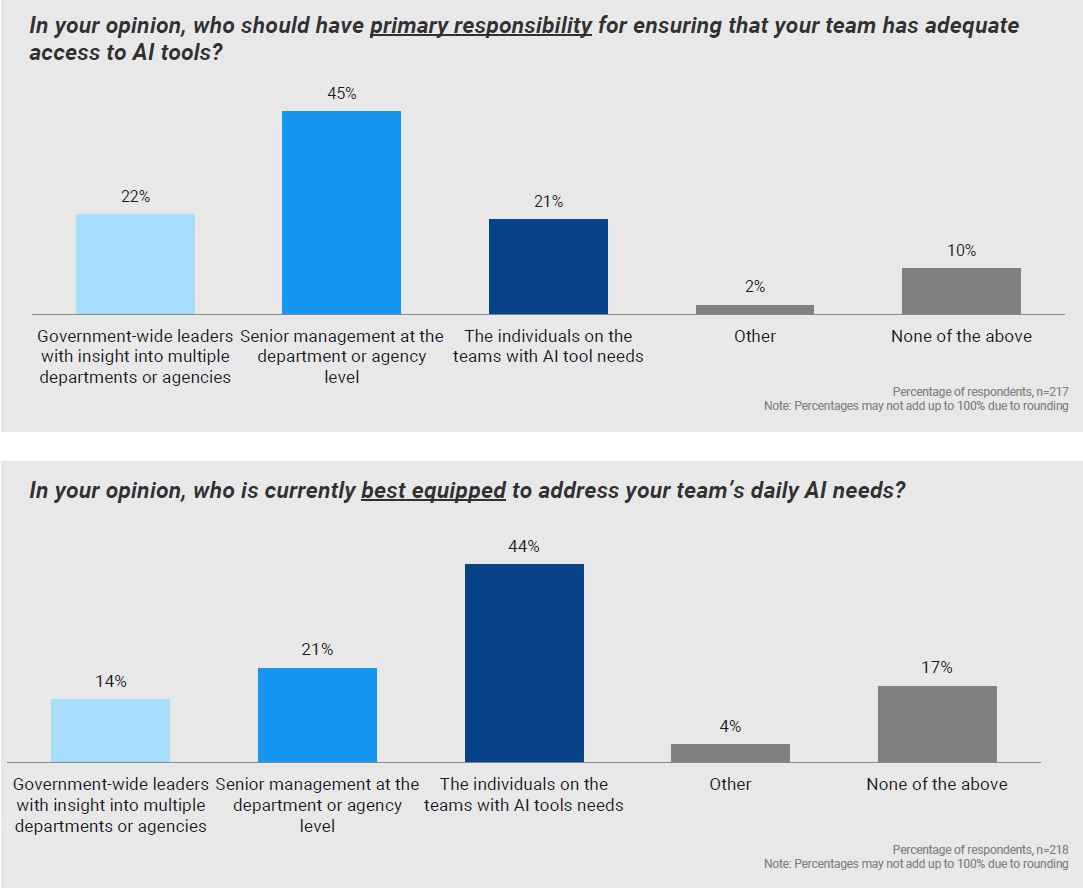

In their feedback, federal respondents reveal a preference for government-wide leadership (22% of those polled prefer this arrangement) or senior management at the department/agency level (45%) to take primary responsibility for ensuring adequate AI access. Of those polled, just one-fifth (21%) believe that the individuals with AI tool needs should be primarily responsible.

When looking at present conditions, a related realization comes to light. More than two-fifths (44%) of the same respondents indicate that the individuals on the team with AI needs are best equipped to address their team's daily needs, while just 21% and 14% believe that senior management at the agency/department level or government-wide leaders are best equipped for this task, respectively. So in a potential future scenario, strategic responsibility could shift upward while daily implementation would be further delegated to specific teams with distinct AI responsibilities.

Conclusion

A large share of public attention on the promise of AI has been focused on particularly flashy commercial applications. While the possibility of self-driving personal vehicles and predictive analytics in private sector solution areas strike directly at our collective imagination, entrepreneurial leaders in the federal government have not trailed far behind.

The key test for public sector organizations outside of the handful of agencies with large, ongoing AI pilots will be agile implementation and fitting cost constraints — with an adequately nimble process, and with sufficiently creative partnerships, opportunities for AI in government have the potential to transcend jurisdictional boundaries and impact a broad variety of organizational priorities.

Appendix

Respondent Profile and Full Survey Data

For a complete profile of the respondents to this survey as well as a topline summary of the survey findings, please click this link.

References

- DARPA: "AI Next Campaign." https://www.darpa.mil/work-with-us/ai-next-campaign

- GCN: "Government leans into machine learning," August 19 2018. https://gcn.com/articles/2018/08/17/machine-learning.aspx

- Nextgov: "How NARA's Helping Agencies on the Path to a Fully Electronic Government," March 28 2019. https://www.nextgov.com/it-modernization/2019/03/how-naras-helping-agencies-path-fully-electronic-government/155902/

- FedTech: "HHS Uses AI Tools to Help Battle Diseases," March 13 2019. https://fedtechmagazine.com/article/2019/03/hhs-uses-ai-tools-help-battle-diseases

- WhiteHouse.gov: "Executive Order on Maintaining American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence," February 11 2019. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-maintaining-american-leadership-artificial-intelligence/

- Government Business Council: "Automating Intelligence," November 1 2018. https://www.govexec.com/insights/reports/automating-intelligence/152486/?oref=insights-river

- Nextgov: "White House Says Agencies Need Industry Help to Execute National AI Strategy," February 28 2019. https://www.nextgov.com/emerging-tech/2019/02/white-house-says-agencies-need-industry-help-execute-national-ai-strategy/155228/

About Government Business Council

As Government Executive Media Group's research division, Government Business Council (GBC) is dedicated to advancing the business of government through analysis, insight, and analytical independence. An extension of Government Executive's 40 years of exemplary editorial standards and commitment to the highest ethical values, GBC studies influential decision makers from across the federal government to produce intelligence-based research and analysis.

Report Author: Igor Geyn

About ViON Corporation

ViON Corporation is a cloud service provider with over 37 years’ experience designing and delivering enterprise data center solutions to government agencies and commercial businesses. The company provides IT as-a-Service solutions including on-premise public cloud capabilities to simplify the challenges facing business leaders and agency executives. Focused on supporting the customer’s evolution to the next generation data center, ViON’s Data Center as-a-Service offering provides innovative solutions from OEMs and disruptive technology providers via a consumption-based model. The complete range of as-a-Service solutions are available to research, compare, procure and manage via a single portal, ViON Marketplace. ViON delivers expertise and an outstanding customer experience at every step with professional and managed services, backed by highly-trained, cleared resources. A veteran-owned company based in Herndon, Virginia, the company has field offices throughout the U.S. (www.vion.com).

About Dell EMC

Dell Technologies’ integrated solutions bring the power of our portfolio together in workload specific solutions such as ready solutions for machine learning and other forms of AI. Sold as an on-premise as-a-service capability in an open model or an easy to deploy and support capital investment for research and development, these solutions accelerate adoption of AI.