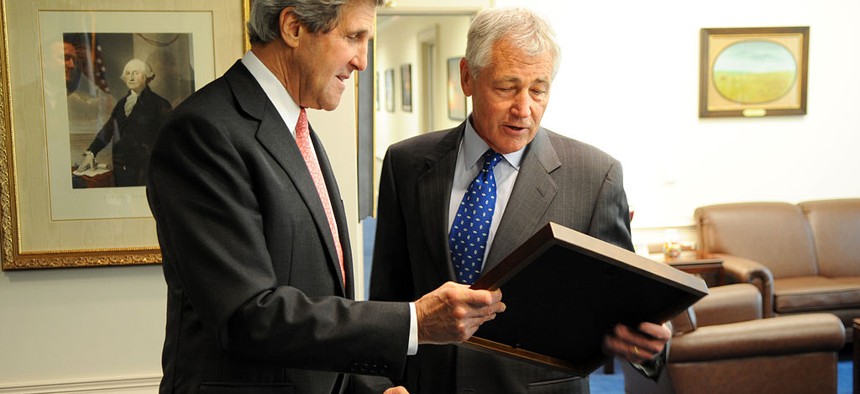

U.S. Department of State (Wikimedia Commons)

Anticipating the 2014 Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review

Four years after then Secretary Hillary Clinton initiated the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review, the State Department and USAID are working on an improved second edition.

The State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development are currently in the midst of a major internal evaluation of their strategic priorities as they prepare to publish their joint Quadrennial Diplomacy and Defense Review later this year. Modeled after the Department of Defense’s Quadrennial Defense Review, the QDDR was initiated in 2010 by then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as an institutional gut check designed to modernize U.S. diplomacy and development for the 21st century. The 2010 edition emphasized the value of civilian power, defined as the combined ability of civilian personnel across federal agencies to advance U.S interests abroad, but many believe it cast too broad a net over strategic priorities to carve a clear path forward. Secretary John Kerry intimated as much when he announced the launch of the 2014 QDDR in April, warning that “this QDDR will not seek to be everything to everybody.” Instead, the Secretary said, the new edition will focus on big challenges and “ask tough questions and pull no punches.”

So how can Tom Perriello, Special Representative for the QDDR, and his team focus their efforts?

- Choose a single theme.The QDDR does not need to elaborate a detailed vision for U.S. grand strategy; the White House’s National Security Strategies do that. What it can do is concentrate on how to improve the way State and USAID wield civilian power abroad in service of that strategy. In a rapidly evolving era of global threats and challenges, developing a holistic whole-of-government approach to executing U.S. foreign policy offers the best way to advance national interests. A new Atlantic Council report on coordination between State and DoD explains that there is now a great opportunity to enhance and institutionalize interagency collaboration as the military rebalances after more than a decade of war in Iraq and Afghanistan. Although it was a theme of the 2010 QDDR, making interagency cooperation, particularly with DoD, the centerpiece of the 2014 edition would provide State and USAID clear guidance in tackling the largest diplomacy and development challenges.

- Develop a clear implementation plan. Narrowing the scope of the QDDR would be an improvement in and of itself, but, to have real impact, the QDDR also needs a clear and measurable implementation plan. Because the 2010 edition did not, some initiatives and priorities were duly acted upon, including reshuffling Under Secretary responsibilities to better address transnational issues, while others were neglected. The Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO) offers a prominent case in point. Established in 2011 as the manifestation of the 2010 QDDR’s conflict prevention and crisis response imperative, the bureau has largely failed to live up to expectations. In a report from March 2014, State’s Office of the Inspector General concluded that CSO’s mission “remains unclear to some of its staff and to many in the Department and the interagency.” The IG further found that “it has yet to develop effective mechanisms for broad-based interagency coordination” despite being charged with organizing a whole-of-government approach to crisis and conflict response.

The QDDR process represents a rare opportunity for State and USAID to reassess their strategic direction. They can make the most of it by zeroing in on interagency coordination of foreign policy execution as the overarching theme and developing a clear and measurable implementation plan.

This post is written by Government Business Council; it is not written by and does not necessarily reflect the views of Government Executive Media Group's editorial staff. For more information, see our advertising guidelines.