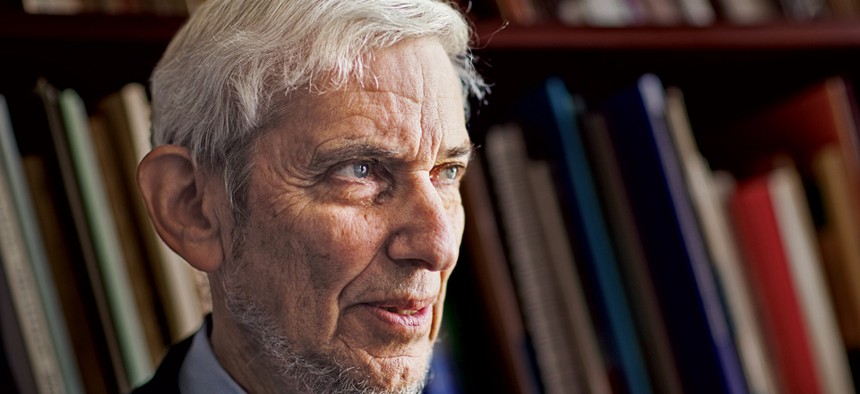

Melissa Golden

Measuring Up

Few people know more about performance metrics than Harry Hatry, director of the Public Management Program at the Urban Institute. Government Executive Deputy Editor Katherine McIntire Peters spoke with Hatry in August at his office in Washington.

Few people know more about performance metrics than Harry Hatry, director of the Public Management Program at the Urban Institute. Government Executive Deputy Editor Katherine McIntire Peters spoke with Hatry in August at his office in Washington.

When you talk about “performance management” what do you mean?

It’s a lot of common sense. It’s regularly tracking the outcomes of government programs—what have they done and how have they helped citizens? The basic building block of that is performance measurement. You can’t do much performance management if you don’t have good performance data.

You say that in the early days, the technology wasn’t there and people weren’t really ready for this. What do you mean?

The focus in the last century was primarily on outputs and unit costs. From a management viewpoint, they did not feel the need to get into the results of that effort. There always were exceptions. You had police departments collecting crime data and there always have been some health departments that were collecting data, but the use for management purposes was highly limited. It just wasn’t the way people were thinking.

What’s happened is since 1993 there’s been tremendous acceptance that you should be doing this. How well you’re doing it, that’s the real problem.

The 1993 Government Performance and Results Act changed that. Did agencies welcome the law?

Probably not. Agencies are naturally skeptical about what’s being imposed on them. In part it’s that a lot of the performance measurement work in the last century was top down and probably still is mostly today. The legislation plus the GPRA Modernization Act in 2010 have been very important in moving this along.

Is this a bipartisan effort?

In general yes. If the Republicans come in they’ll rename it or make changes. But it’s been a progression. There’s no question there’s been an underlying theme of good performance measurement and evaluation that has been sustained over the years and has grown. Ideology often gets into and will drive out the use of the data. But managers throughout any agency make hundreds of decisions that involve some form of resource allocation. Many of those can be aided by good performance data.

Your new report, “Transforming Performance Measurement for the 21st Century,” says most PM systems are shallow. What do you mean?

The information on outcomes and results is scarce. It was more on collecting data on response times, which is important but it doesn’t tell you whether the response is good or effective. There was a lack of feedback from those affected by government services. That’s now beginning to receive attention. In addition, information on the sustainability of good outcomes for customers has been neglected. In many health and human services, the issue is not simply to get the person to complete the service, but you want their health or income or employment to be sustained afterwards.

Most performance measurement systems, which primarily are reported annually, do not provide enough detailed information. It really becomes much more useful to a manager if they can look at outcomes for various populations or various types of services—if they can collectively look at that they can make much more informed decisions.

There’s considerable data out there, but what also should be part of a performance measurement process, to help performance management, is to require explanations—why the data is worse than last year, why one ethnic group or gender is not doing as well. There has not been a really decent process that asks for and gets explanations for unexpectedly poor or good results.

You say technology is creating new tools and opportunities.

The ability to get quick, accurate data on outcomes potentially is a major advancement. We’ve entered a period when a manager, perhaps in his car or at home or sitting at his desk, can obtain outcome data he needs. If he’s talking to a group of citizens, he can potentially pull down that data, sorted by location or demographic characteristics, he can look at service alternatives—the technology is wonderful. Data visualization is another part of this—being able to present the material in a way that managers can easily understand is very important.

A key issue is to have software that is user-friendly. I can’t overstate that problem.

Do managers have the right skills to do this well?

It’s a good question. Some managers, maybe most of them, are people people, not data people. Program managers should be able to handle the basics—they need to know how to be able to use the data. It gets back to the user-friendliness of the software. We’re not completely there yet, but we’re awfully close. That will ease the burden on the manager to have special knowledge of computers and software.

Your report talks about measuring the right things. You cite how the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services collects data on patients who smoke and patients who receive cessation intervention, but no data on whether smokers give up the habit as a result. How common is that sort of omission?

It’s quite common. How often after you visit a doctor does that doctor follow up and call to find out whether you’re now in good shape? We just don’t do it. Partly it’s the cost issue. Certainly CMS is doing an awful lot of work in the evaluation area, but important information such as what happens to people after they exit government services often has been neglected. I still can’t believe that example exists.

How can agencies avoid incentivizing the wrong behavior, as seemed to happen at Veterans Affairs with the scheduling scandal?

Managers, for good reason, don’t like to show poor performance against their targets. They get besieged by the press and [the Office of Management and Budget] and Congress. They haven’t learned how to handle poor data. It’s difficult. One way to handle it is to ask for more money. In the case of the VA, it’s clear they were understaffed. In any case, agencies need adequate data quality control. And when poor results have occurred the agency should itself report the data and also identify its plan for correcting the problem.

NEXT STORY: Around Government