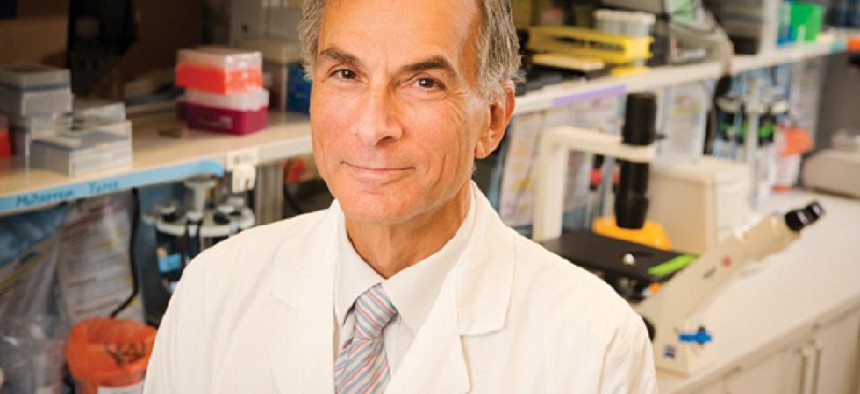

Sam Kittner/Kittner.com

The NIH Doctor Who Pioneered Life-Saving Treatments

Dr. Neal Young of the NIH saved the lives of thousands of people suffering from a deadly blood disorder.

For years, patients with severe aplastic anemia died within months of developing the rare blood disease. Dr. Neal Young has increased the survival rate to 80 percent.

In his work at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Young has combined pioneering basic laboratory science, clinical research, and direct patient care to save the lives of thousands of people suffering from a blood disorder that wipes out the cells in the bone marrow, including red blood cells that carry oxygen, white blood cells that fight infection and platelets that help clot the blood.

Young conceived, designed and headed the first multicenter clinical trial in the United States for immunosuppressive therapy for aplastic anemia. The regimen he developed for this blood disease has become standard therapy for patients all over the world. This disease strikes about 600 to 900 people a year in the United States, and thousands across the globe.

“Neal has completed an amazing series of landmark clinical trials and published results that have taken what was a fatal disease in the early 1980s to one that now has a survival rate of 80 percent or more in the long-term,” said Dr. Cynthia Dunbar of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute at NIH.

Because of Young’s efforts, his clinic at NIH is today considered one of the world’s major referral centers for patients with bone marrow failure syndromes.

As chief of the Hematology Branch of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Young is continually building on his significant accomplishments. He developed an understanding of how the highly contagious B19 parvovirus infects cells of the bone marrow and showed its role in disease among patients, especially those with sickle cell anemia and others with defective immune systems. He developed ways to test for and diagnose this virus, came up with a treatment and currently has a vaccine in clinical trials that, if successful, will protect vulnerable patients.

Young also has made landmark discoveries linking genetic defects—mutations or mistakes in the DNA sequence—to the break down in cells and as a cause of aplastic anemia. In addition, Young has implicated the same type of genetic mutations linked to aplastic anemia much more broadly to liver cirrhosis, lung fibrosis and leukemia. These findings may offer clues to improving treatment and patient outcomes for these common and devastating diseases.

Dr. Ching-Hon Pui, chairman of the Department of Oncology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Tennessee, said Young’s work in hematology “has totally transformed the field.”

“His impact has been truly global,” said Pui. “I cannot think of another hematologist with comparable accomplishments.”

This is the fourth in a series of profiles featuring the recipients of the 2012 Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals. Presented to outstanding public servants by the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service, and sponsored in part by Bloomberg, Booz Allen Hamilton, The Boston Consulting Group, Chevron and United Technologies Corporation, the prestigious Sammies awards are offered in nine categories. To nominate a federal employee for a 2013 medal go to servicetoamericamedals.org.NEXT STORY: 6 Tips for Giving Effective Critical Feedback