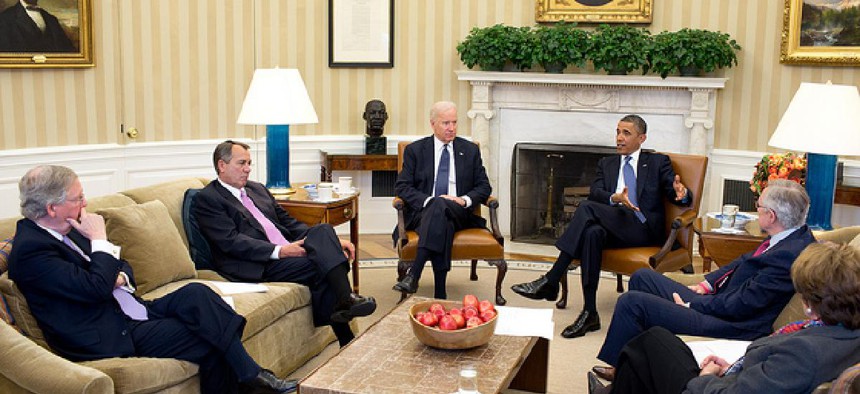

After returning early from his Christmas vacation, the President with the Vice President meets in the Oval Office with the leadership of Congress to discuss the fiscal cliff, Dec. 28, 2012. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Analysis: Obama and the Perils of Being Aloof

Willingness to schmooze can make the difference between a good and great presidency.

There is a delicious scene in the movie "Lincoln" in which the first couple discuss an upcoming dinner party at the White House. Mary Todd Lincoln can't figure out why her husband, a famed loner who openly loathes Washington society, invited rival Democrats and radical Republicans to his home. Suddenly, it dawns on her: the 13th Amendment!

Abraham is going to try to wipe slavery from the U.S. Constitution, Mrs. Lincoln concludes with an accusatory glare, and he's going to start by schmoozing key lawmakers!

It's a lesson Barack Obama could learn from history.

"This is one of the biggest failures of his presidency, the inability ... to work with his adversaries, to work with the press, to pay people the respect they're due or that they think they're due," said John Baick, professor of history at Western New England University in Springfield, Mass. "Sometimes, the smallest gestures go a long way. There is an impatience for playing the game that shines through with President Obama."

In his book, "The Price of Politics," Bob Woodward portrays the president as a distant character who spends little time forging relationships with members of Congress, and who has equally cool relationships with the business community.

Obama considers himself above deal-making and back-slapping, political necessities he often delegates to Vice President Joe Biden and other lesser sorts.

By Woodward's account, the supremely self-confident Obama thought he had House Speaker John Boehner pegged as the type of Republican he knew in the Illinois legislature. "John Boehner is like a Republican state senator," the president told staff, according to Woodward. "He's a golf-playing, cigarette-smoking country-club Republican who's there to make a deal. He's very familiar to me."

But several sources involved in the most recent budget negotiations between Obama and Boehner tell me that the president failed to connect with Boehner. The president dominated conversations and had a habit of describing the speaker's political options at length, which Boehner found both boring and insulting.

Obama rarely invested time in getting to know Boehner. Woodward reported this telling anecdote: After the 2010 elections made Boehner the incoming speaker, Obama couldn't make a congratulatory call until the White House scrambled to find his telephone number, eventually turning to a fishing pal of somebody who worked for Boehner.

Obama might do well to remember that his fast rise from the state senate in Illinois was due in large part to an uncanny ability to make friends and find mentors. In Springfield, Ill., he played in regular poker game with lawmakers and lobbyists, and impressed elders with an ability to see things through others' eyes, a natural empathy that helped him reach across party lines and forge hard compromises on the death penalty, racial profiling and ethics legislation.

One of Obama's most impressive attributes is his quiet confidence: Voters sense that he is comfortable in his own skin, a dedicated father and friend who won't waste time with the phony rituals of Washington. But his above-it-all style comes at a price.

That steep cost led me to write yesterday that Obama shares an unhelpful attribute with his Defense secretary nominee, Chuck Hagel: Both men are aloof contrarians who don't suffer fools well. Some readers objected, saying Obama shouldn't be criticized for holding Washington at arm’s length. "It's not a bad thing" to be aloof, one reader tweeted.

While it may be understandable, even admirable, to keep a distance from an unpopular Congress, my point is that it's not good politics.

For Hagel, he now faces a rocky confirmation in part because he lacks allies on Capitol Hill: During his two terms in the Senate, Hagel rankled Republican and Democratic colleagues with a demeanor that suggested he was too good for them and their views.

For Obama, learning how to schmooze could mean the difference between a good and great presidency. Franklin Roosevelt, Lyndon Johnson, Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton (to name just a few) were masters at building relationships that furthered their political aims. They dined and drank with lawmakers, and they ventured to Capitol Hill out of respect. Johnson was an aggressive phone-caller. Roosevelt mixed cocktails for guests. Clinton flattered House Speaker Newt Gingrich.

In her masterpiece on Lincoln, "Team of Rivals," Doris Kearns Goodwin, said the great emancipator "displayed uncommon magnanimity toward those who opposed him." In a new book on Lincoln, "Rise to Greatness," author David Von Drehle writes about a party the Lincolns threw in 1862 for cabinet members and selected lawmakers. A few invitees refused to attend, protesting festivities in a time of such peril. "Are the president and Mrs. Lincoln aware there is a Civil War?" sniffed one senator.

But the party was a success. "It was Mary's triumph as first lady," Von Drehle writes, "and it gave her husband a valuable lift among Washington's elite at a moment when that small but influential world harbored great doubts about his fitness to lead the country out of the wilderness of war."

At the start of his second term, one wonders less about Obama's fitness than his willingness: Why doesn't he do more to build and maintain the relationships required to govern in era of polarization?