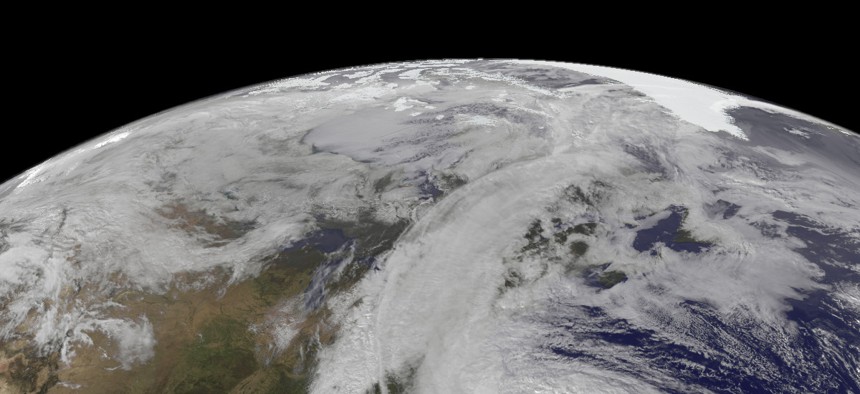

Satellite image of Hurricane Sandy (NASA)

Why Climate Change Joined GAO's High-Risk List

The Government Accountability Office has stepped into new territory by adding climate change to its list of the 30 most high-risk challenges facing the federal government.

Typically, we think of the GAO focusing on territory familiar to auditors, which is what most of the high-risk list does: managing federal property, DOD supply chain management, NASA acquisitions management, modernizing federal disability programs, etc. But it has now added a politically-charged topic to its list: climate change.

First, some background. The GAO High Risk List was first compiled in 1990. Since then, about one-third of the issues have been removed, and new ones added. It has created a web page devoted to tracking these issues. In testimony before the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee last week, Comptroller General Gene Dodaro reported that GAO removed two programs and added two new ones to the list.

The media captured the details of the overall list and his testimony, but I’d like to focus on one of the two new ones: “Limiting the Federal Government’s Fiscal Exposure by Better Managing Climate Change Risks.”

How does an issue get onto the GAO High Risk List? GAO has four criteria:

- whether the program or function is of national significance;

- whether it is key to government performance and accountability;

- whether the risk involves public health or safety, service delivery, national security, national defense, economic growth, or privacy or citizens’ rights;

- whether it could result in significant impaired service, program failure, injury or loss of life, or significantly reduced economy, efficiency, or effectiveness.

GAO concludes: “Climate change poses risks to many environmental and economic systems—including agriculture, infrastructure, ecosystems, and human health—and presents a significant financial risk to the federal government.”

Possible policy responses to climate change range from: prevention or reversal (which would require reducing carbon emissions, as envisioned by several global conventions, such as the Kyoto Protocol); adaptation (which would be accepting that climate change will happen, and the goal is to reduce the impact); or no action. GAO selected the middle option. Rather than focusing on the climate effects, it focuses on the fiscal effects it will have on the federal budget.

What is its rationale for doing this? GAO says: “Climate change adaptation—defined as adjustments to natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climate change—is a risk-management strategy to help protect vulnerable sectors and communities that might be affected by changes in the climate.”

Policymakers increasingly view climate change adaptation as a risk management strategy to protect vulnerable sectors and communities that might be affected by changes in the climate, but, as we reported in 2009, the federal government’s emerging adaptation activities were carried out in an ad hoc manner and were not well coordinated across federal agencies, let alone with state and local governments. . .the impacts of climate change can be expected to increase fiscal exposure for the federal government in many areas:

Federal government as property owner. The federal government owns and operates hundreds of thousands of buildings and facilities, such as defense installations, that could be affected by a changing climate. In addition, the federal government manages about 650 million acres––29 percent of the 2.27 billion acres of U.S. land––for a wide variety of purposes, such as recreation, grazing, timber, and fish and wildlife. . . .

Federal insurance programs. Two important federal insurance efforts—the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation—are based on conditions, priorities, and approaches that were established decades ago and do not account for climate change. . . .

Technical assistance to state and local governments. The federal government invests billions of dollars annually in infrastructure projects that state and local governments prioritize and supervise. These projects have large up front capital investments and long lead times that require decisions about how to address climate change to be made well before its potential effects are discernable. . . .

Disaster aid. In the event of a major disaster, federal funding for response and recovery comes from the Disaster Relief Fund managed by FEMA and disaster aid programs of other participating federal agencies. The federal government does not budget for these costs and runs the risk of facing a large fiscal exposure at any time.

GAO’s Conclusion and Recommendation. GAO concludes: “The federal government would be better positioned to respond to the risks posed by climate change if federal efforts were more coordinated and directed toward common goals. . . In May 2011, we found no coherent strategic government-wide approach to climate change funding and that federal officials do not have a shared understanding of strategic government-wide priorities.”

It goes on to recommend “a government-wide strategic approach with strong leadership and the authority to manage climate change risks that encompasses the entire range of related federal activities and addresses all key elements of strategic planning.”

It will be interesting to see how both the executive and legislative branches respond.