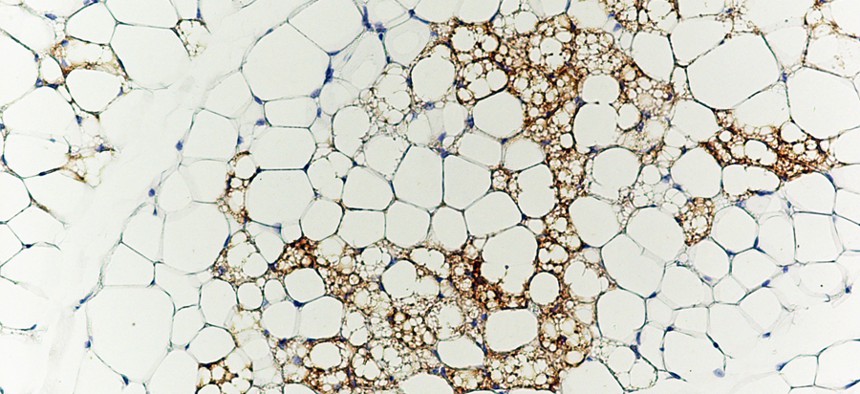

Patrick Seale, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Brown fat cells (stained brown with antibodies against the brown fat-specific protein Ucp1) nestled in amongst white fat cells.

Fat has been villainized; but all fat was not created equal. Our two main types of fat—brown and white—play different roles. Now, two teams of NIH-funded researchers have enriched our understanding of adipose tissue. The first team discovered the genetic switch that triggers the development of brown fat, and the second figured out how the body can recruit white fat and transform it into brown.

Why would we want to change white fat into brown? White fat stores energy as large fat droplets, while brown fat has much smaller droplets and is specialized to burn them, yielding heat. Brown fat cells are packed with energy generating powerhouses called mitochondria that contain iron—which gives them their brown color. Infants are born with rich stores of brown fat (about 5 percent of total body mass) on the upper spine and shoulders to keep them warm. It used to be thought that brown fat disappeared by adulthood—but it turns out we harbor small reserves in our shoulders and neck.

In mice, brown fat does something remarkable: it burns more calories when mice are overfed, protecting them from obesity. (Don’t you wish eating a plate of fries did that for you?) Furthermore, mice genetically predisposed to have with extra brown fat are actually leaner and healthier. In humans, there is evidence that more brown fat is associated with a lower body weight. So, how might we increase our brown fat production?

The team led by the University of Pennsylvania figured out the switch for creating a brown fat cell—a protein called early B cell factor-2 (Ebf2). Comparing the active genes in brown and white fat cells, they discovered Ebf2 is present in larger quantities in brown fat. This protein seems to mark which genes will later be turned on to transform certain types of precursor cells into brown fat. When the team engineered mice lacking this protein, the animals had white fat cells on their upper back and spine rather than the typical brown. When the team expressed high levels of Ebf2 in white fat, these cells turned brown and consumed more oxygen—a sign they were producing more heat.

The second team, led by Harvard’s Joslin Diabetes Center, noted that mice have two types of brown fat: constitutive brown fat, which they have from birth, and “recruitable” brown fat, scattered throughout the muscles and white fat. When researchers engineered mice lacking a protein called Type 1A BMP-receptor (BMPR1A)—which is needed for the correct development of brown fat—the mice were born with just a tiny bit of constitutive brown fat on their back.

You would think that these mice would be terribly cold. Surprisingly, they kept a normal body temperature. How did they manage this feat?

The lack of brown fat apparently sends a signal via the brain to the recruitable fat cells, telling them to make the switch and transform into brown fat. The mice stayed warm, and the recruited brown fat even protected them from obesity.

In humans, too much abdominal white fat promotes heart disease, diabetes, and many other metabolic diseases. It would be potentially therapeutic if we could transform some of our white fat into brown. Determining which genes control the development of white and brown fat may be the first step toward developing game changing treatments for diabetes and obesity.

NIH funding: the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences