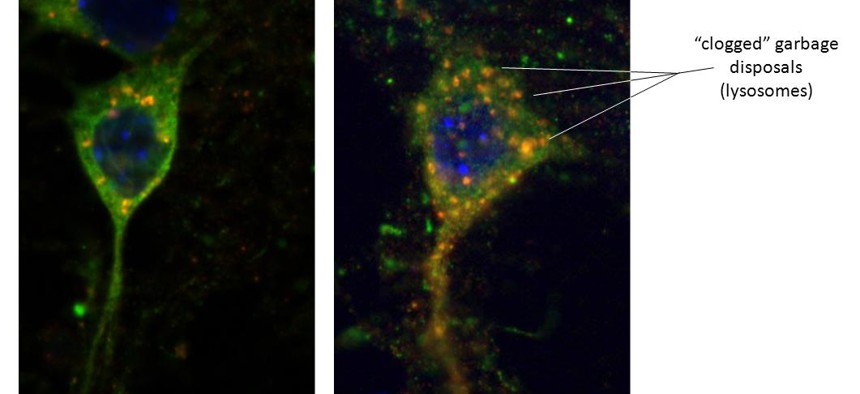

Left - Healthy neuron with alpha-synuclein (green) protein. Red dots are trash lysosomes with alpha-synuclein entering, hence an orange hue. Right - Sick neuron from LRRK2 brain. Lysosomes are enlarged as the alpha-synuclein is unable to enter the trash. Image courtesy of Samantha Orenstein and Dr. Esperanza Arias, Department of Developmental and Molecular Biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York

NIH Gains New Insight Into Cause of Parkinson’s Disease

NIH-funded research may have discovered a key cause of the disease.

I’m blogging today to tell you about a new NIH funded report describing a possible cause of Parkinson’s disease: a clog in the protein disposal system.

You probably already know something about Parkinson’s disease. Many of us know individuals who have been stricken, and actor Michael J. Fox, who suffers from it, has done a great job talking about and spreading awareness of it. Parkinson’s is a progressive neurodegenerative condition in which the dopamine-producing cells in the brain region called the substantia nigra begin to sicken and die. These cells are critical for controlling movement; their death causes shaking, difficulty moving, and the characteristic slow gait. Patients can have trouble swallowing, chewing, and speaking. As the disease progresses, cognitive and behavioral problems take hold—depression, personality shifts, sleep disturbances.

The disease affects 1 in 100 people over the age of 60, but it can strike earlier, too—as it did for Michael J. Fox. Recent detailed studies of the brain in Parkinson’s disease have shown that the dying nerve cells are filled with toxic blobs of a protein called alpha-synuclein, which is an important component of nerve cell health. But what causes this protein to form clumps? That’s what this new study may be revealing.

While most forms of Parkinson’s are sporadic, there are rare familial types in which a misspelled gene raises the likelihood of developing the disease. Rare families have misspellings in alpha-synuclein itself, causing the protein to be stickier and more likely to form aggregates. But the most common cause of the familial form of Parkinson’s disease can be traced to misspellings in the LRRK2 (pronounced “lark-2”) gene—which then produces an abnormal LRRK2 protein. The authors of this new study, led by a team at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, found that healthy versions of the LRRK2 protein are rapidly degraded in a disposal compartment in the cell called a lysosome—but the mutant forms are not. How might mutations in LRRK2 eventually cause the alpha-synuclein protein to accumulate?

Cells need to get rid of their used up byproducts. When they don’t, the “trash”—old and damaged proteins—builds up and becomes toxic, just like your house would be if you never took out the trash. In one disposal method, a “chaperone” protein targets the unwanted or damaged protein and escorts it to the lysosome, where it is digested by enzymes, broken down, and the building blocks are recycled. But when the LRRK2 protein is mutated, it apparently gums up the entire system. Lots of proteins targeted for disposal (including LRRK2 itself) are blocked from proper processing. The most serious consequence is that alpha-synuclein is prevented from entering the lysosome and being recycled—causing it to build up as toxic aggregates in the cells.

An exciting aspect of this research is that investigators in other fields have identified certain compounds that might be capable of re-booting the chaperone-mediated garbage disposal system, potentially facilitating the breakdown of the toxic alpha-synuclein bundles. Though it will require many more steps to test that idea, this is an intriguing new approach to tackling this crippling disease.

References:

Interplay of LRRK2 with chaperone-mediated autophagy. Orenstein SJ, Kuo SH, Tasset I, Arias E, Koga H, Fernandez-Carasa I, Cortes E, Honig LS, Dauer W, Consiglio A, Raya A, Sulzer D, Cuervo AM. Nat Neurosci. 2013 Mar 3.

For more information:

Parkinson’s disease, A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia, National Library of Medicine, NIH

Parkinson’s Disease Information Page

Parkinson’s Disease Research Overview (recommended for scientists)

Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research

NIH funding: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke