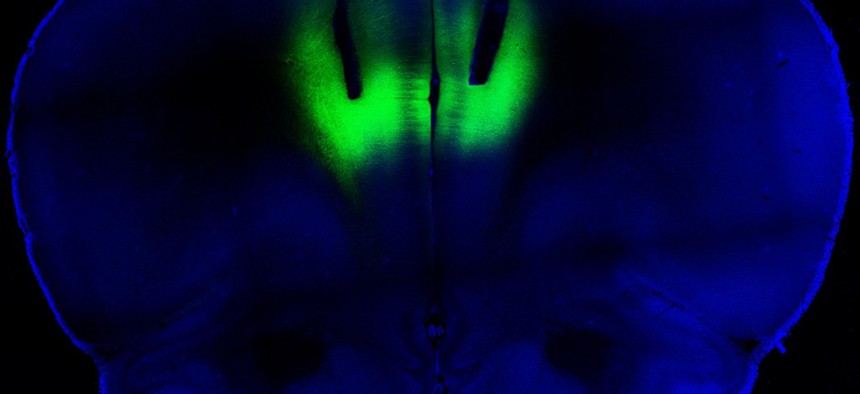

Optogenetic stimulation using laser pulses lights up the prelimbic cortex. Courtesy of Billy Chen and Antonello Bonci

NIH Shines a Bright Light on Cocaine Addiction

New research technique uses lasers to reveal root of addiction.

Wow—there is a lot of exciting brain research in progress, and this week is no exception. A team here at NIH, collaborating with scientists at the University of California in San Francisco, delivered harmless pulses of laser light to the brains of cocaine-addicted rats, blocking their desire for the narcotic.

If that sounds a bit way out, I can assure you the approach is based on some very solid evidence suggesting that people—and rats—are more vulnerable to addiction when a region of their brain in the prefrontal cortex isn’t functioning properly. Brain imaging studies show that rat and human addicts have less activity in the region compared with healthy individuals; and chronic cocaine use makes the problem of low activity even worse. The prefrontal cortex is critical for decision-making, impulse control, and behavior; it helps you weigh the negative consequences of drug use.

Addiction is an enormous public health issue. Currently, 1.4 million Americans are addicted to cocaine—and no treatment has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, making it one of the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s top research priorities.

So let me first say that nerve cells, or neurons, don’t typically respond to laser beams. The rats in this experiment were engineered to carry light-activated neurons within a part of their prefrontal cortex called the prelimbic cortex. The rats were then fitted with optic fibers to transmit the laser pulses. This technique, called optogenetics, was actually invented by a recipient of the NIH’s Pioneer Award, and it will likely contribute significantly to the BRAIN initiative just announced by President Obama.

The researchers studied rats that were chronically addicted to cocaine. Their need for the drug was so strong that they would ignore electric shocks in order to get a hit. But when those same rats received the laser light pulses, the light activated the prelimbic cortex, causing electrical activity in that brain region to surge. Remarkably, the rat’s fear of the foot shock reappeared, and assisted in deterring cocaine seeking. On the other hand, when the team used a different optogenetics technique to reduce activity in this same brain region, rats that were previously deterred by the foot shocks became chronic cocaine junkies.

Clearly this same approach wouldn’t be used in humans. But it does suggest that boosting activity in the prefrontal cortex using methods like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which is already used to treat depression, might help. In fact, clinical trials at the NIH are scheduled to begin soon. The researchers plan on using TMS to bump up activity in the prefrontal cortex and see if it decreases addictive behaviors in people.

Want to learn more? Check out these two resources from the NIH’s National Institute on Drug Abuse.

NEXT STORY: Obama Budget Would Increase Federal Workforce