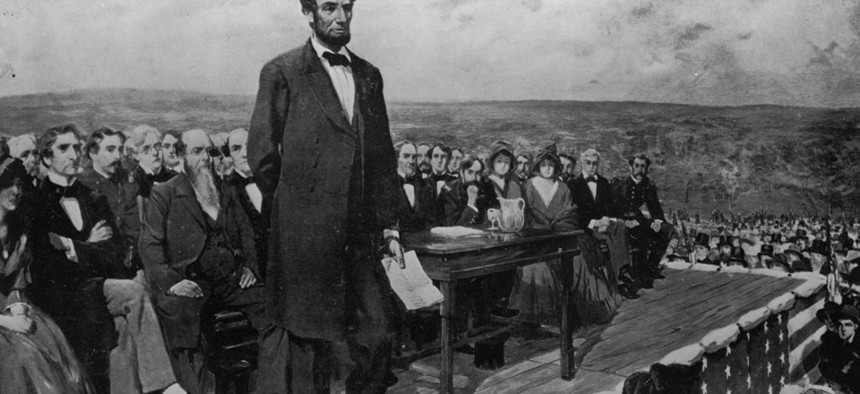

Library of Congress

Presidential Speeches Were Once College-Level Rhetoric—Now They're for Sixth-Graders

Are the presidents dumbing down? Or are their speechwriters smartening up?

Is political rhetoric becoming less sophisticated over time? One interesting way to answer the question is to study the complexity of presidential speeches, from George Washington's first inaugural to the recent addresses of Barack Obama.

To do that, the site Vocativ used the Flesch-Kincaid readability test, which was developed by the U.S. Navy in the 1970s to ensure the simplicity of military instruction manuals. The Flesch reading formula is not a measure of vocabulary or the technical construction of sentences. Instead, it measures two variables—syllables per word and words per sentence. So a cryptic sentence like this:

As mist slunk in, the oiler on the rig slewed the boom of the crane.

actually has a lower (simpler) Flesch score than this sentence of equal words:

The cat was so happy after eating the goldfish that it made a big smile.

because happy , after , eating , and goldfish have two syllables, even though they're far more common than one-syllable words like slunk , rig , slew , or boom .

With that caveat out of the way, here is a look at presidential-speech complexity over time. Lower scores mean simpler speeches. Bigger circles mean longer speeches.

Simpler Times: Presidential Speeches Through History

The upshot is that up to the 1850s, most presidential addresses were what modern Flesch scores would consider college-level rhetoric. Since the 1940s, presidential addresses have often been at a sixth-grader's level.

And despite the impression that Obama restored old-fashioned flourishes to the White House after George W. Bush, Flesch scores grade both candidates at about the same upper-elementary-school level. (If you object to the comparison for whatever reason, recall that Flesch measures words and syllables, not quality of inspiration.)

Modern Presidential Speeches: GWB vs. BHO

Three observations for the road:

1. Presidential rhetoric is becoming simpler because the country is becoming more democratic.

“It's tempting to read this as a dumbing down of the bully pulpit,” says Jeff Shesol, a historian and former speechwriter for Bill Clinton. “But it’s actually a sign of democratization. In the early republic, presidents could assume that they were speaking to audiences made up mostly of men like themselves: educated, civic-minded landowners. These, of course, were the only Americans with the right to vote. But over time, the franchise expanded and presidential appeals had to reach a broader audience.”

Indeed, the major shift downward in presidential complexity happens around 1920, which coincides with at least four positive developments: (1) the 17th Amendment allowing direct election of senators in 1913; (2) the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote in 1920; (3) the movement to make public education mandatory in the 1920s; (4) the invention of radio, which passed 50 percent penetration among US households by the 1930s. TV passed the 50-percent threshold in the early 1950s. *

2. Complex speeches aren't better speeches. In fact, they're worse.

The most memorable lines in modern rhetoric—"Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country"; "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself"; —are remembered precisely because they're simple enough to understand, memorize, and talk about. Practically every modern sage of language—George Orwell, Steven Pinker, William Safire, Strunk & White—advises non-fiction writers to express themselves with simple language. Even if you like purple prose in your long-form narrative non-fiction, you'll agree that it's pleasing to hear complex policy points in clear sentences and parallelisms. (It's hard to rule out that the dense language of the 19th century was pleasing and cogent in its own time.)

3. Even if you think that democratization and simple language aren't always good, there is no chance you want presidential candidates talking like George Washington.

Here is the beginning of President Washington's first inaugural address, which he delivered to a joint session of Congress, where there were no recording devices to beam the words to a broader audience. The Flesch reading-ease formula ranks it as one of the most difficult speeches in American history. We'll go sentence by sentence. (W arning : These are absurdly long, excruciatingly overwrought, unforgivably dense sentences)

Among the vicissitudes incident to life, no event could have filled me with greater anxieties than that of which the notification was transmitted by your order, and received on the fourteenth day of the present month.

Okay so: "I received a letter a few weeks ago that made me conflicted."

On the one hand, I was summoned by my Country, whose voice I can never hear but with veneration and love, from a retreat which I had chosen with the fondest predilection, and, in my flattering hopes, with an immutable decision, as the asylum of my declining years: a retreat which was rendered every day more necessary as well as more dear to me, by the addition of habit to inclination, and of frequent interruptions in my health to the gradual waste committed on it by time.

"You interrupted my exquisite and much-needed retirement by electing me as your president."

On the other hand, the magnitude and difficulty of the trust to which the voice of my Country called me, being sufficient to awaken in the wisest and most experienced of her citizens, a distrustful scrutiny into his qualifications, could not but overwhelm with despondence, one, who, inheriting inferior endowments from nature and unpracticed in the duties of civil administration, ought to be peculiarly conscious of his own deficiencies.

"Folks, it's hard to be the president."

George Washington deserves to be remembered. But this, the first chapter of U.S. presidential-speech history, is duly forgotten. The gradual simplification of political rhetoric is, even Washington might agree, one of the less despondent vicissitudes incident to life.