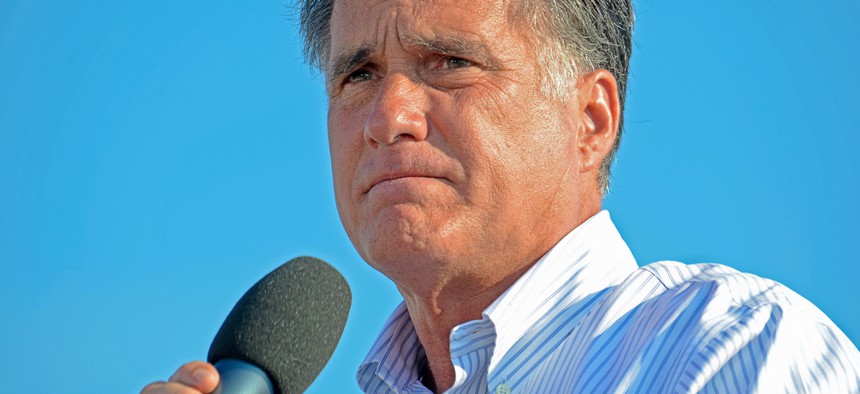

Maria Dryfhout / Shutterstock.com file photo

Four Reasons Why Romney Is a 2016 Long-Shot

The 2012 nominee's biography, baggage, and recent history seem a toxic cocktail for another run.

When Mitt Romney speaks at the Republican National Committee's winter meeting Friday evening, it will be the first time that he's addressing his newfound interest in another presidential campaign. It will also be his first chance to offer party stalwarts an effective argument for why he thinks he'd be able to run a competitive race the third time around. It's an extremely difficult case to make.

If he decides to run, the odds of him struggling from the outset are high. Romney has lost many of the advisers, donors, and supporters who backed him four years ago. The field is much more crowded and talented than it was in the last nomination fight. He'd have to dramatically retool his message, while giving fresh fodder for attacks that he's a flip-flopper (yet again). The last time an unsuccessful presidential nominee ran after losing was in 1984, when George McGovern mounted a quixotic bid—a hint of how much of a challenge Romney faces.

"This will go one of two directions—either he crashes and burns early in the process, or he's right and GOP primary voters say they made the right choice last time and the country didn't get it, but this time they will," said one veteran Republican strategist.

Expecting Republicans to be looking for a Romney revival is a very risky bet, especially considering how long it took Romney to lock up the nomination against a second-tier field in 2012. Here are the four biggest reasons Romney would struggle to compete for the presidency on his third try, if he decides to reenter the political arena:

1. To win the nomination in 2016, Romney would need to pander to the Right more than he did last time. That would be toxic in a general election.

For all the grief Romney got for moving too far to the right in the 2012 primary, he had the luxury of facing a weak crop of conservative challengers while being the only establishment-approved candidate. That won't be the case in 2016, with the establishment side of the field looking awfully crowded. To distinguish himself to GOP primary voters, Romney would have to again prove his conservatism—and that's what dogged him in the last general election.

One of the most telling comments from Romney's inner circle was that the candidate would run more conservatively on immigration than Jeb Bush. To those who remember Romney's self-deportation line at a primary debate, it was reminiscent of a tin-eared campaign that dogged him throughout. In the primary, it would certainly offer Romney an opportunity to contrast himself from Bush and several other candidates with more-moderate records on the issue. But for a candidate who performed dismally with Hispanic voters and struggled to broaden the GOP electorate, it's hard to see how he could campaign more conservatively and perform any better in a general election than he did last time.

2. Romney ran on his business credentials as the economic fix-it candidate in 2012. The economy is looking in better shape for 2016.

For all his political challenges, Romney presented a persuasive argument for why voters should back him over President Obama—his business experience is what's necessary to boost a stagnant economy. But there are signs that the economy is improving, with gas prices down, the stock market near record levels, and consumer confidence inching upwards. It was notable that Jeb Bush's exploratory-committee statement acknowledged that the economy was in good shape for some Americans but wasn't helping the middle class—a statement referencing income inequality that would never have come from Romney.

If he was the nominee, what would he run on? If the economy improves enough, the GOP nominee's strongest arguments will be over more polarizing issues—foreign policy, the president's health care law, excessive environmental regulations, to name a few. Not to mention a desire for change after eight years of a Democratic president. On most of those counts, Romney is a weak messenger. On health care, Romney struggled to articulate his case against the president's health care law, given that he championed similar reforms as governor of Massachusetts.

And while Romney's foreign policy debate performance burnished his commander-in-chief chops, Romney never made the subject a central issue of his campaign.

3. Economic mobility is emerging as a leading issue, even for Republicans. Romney's biography (and his "47 percent" gaffe) is a fundamental handicap.

Economic mobility is the cause celebre in both parties these days. (Democrats, like Elizabeth Warren, prefer to use the rhetoric of income inequality.) Sens. Paul Ryan, Marco Rubio, and Rand Paul have all focused on tackling poverty in recent years. The name of Jeb Bush's PAC, "The Right to Rise," suggests it's going be the central focus of his presidential campaign. Even the hard-line-conservative Heritage Action for America is talking about solutions to help struggling middle-class voters.

Romney is expressing a renewed interest in the subject, but he didn't demonstrate it enough in the last presidential campaign. His "47 percent" comment at a fundraiser, separating the American electorate into makers and takers, has been condemned by Republicans of all ideological stripes since the election. When Paul Ryan wanted to spend more time on the campaign trail highlighting poverty, Romney's campaign resisted.

One of the biggest reasons Romney lost is because Americans didn't view him as relatable—and much of that problem was fundamental to his biography. Democrats had a wealth of material to use in portraying his successful business background as something far more sinister. That won't change if he runs again, even if he campaigns on a different message.

4. The Republican electorate wants change. Romney is a symbol of the past.

Bush's biggest vulnerability is also Romney's. Voters from all parties are dissatisfied with the current state of politics, and want to see fresh faces emerge. That desire for change is a major handicap for Hillary Clinton, who's an all-too-familiar symbol of the past. By nominating a Romney (or Bush), Republicans would be taking away Clinton's biggest vulnerability.

Romney understood this political reality better than anyone in the wake of his defeat. When asked if he was interested in running again, he emphasized that it was time for a new generation of GOP leaders, even citing many of them by name. "We have a very strong field of leaders who could become our nominee—and could stand up for the kind of leadership I think America wants," Romney told CBS's Face the Nation last March. Now, by running, he's suggesting that the large field of candidates is uninspiring. He was right the first time.

(Image via Maria Dryfhout / Shutterstock.com )