Sledding as a Revolutionary Act

The children who defied the rules to play in the snow on Capitol Hill stand in a grand American tradition.

"If you are up for a bit of civil disobedience," read the invitation , "meet at the west front of the Capitol lawn at 1:00 today. Come armed with sleds!"

It was a small protest, scaled to match the size of the injustice. "There are really serious problems out there in the world," its organizer told the National Journal . "I thought this was one little thing I might be able to change." The sledders were met on the snow-covered slopes in the shadow of Congress by the Capitol Police, politely distributing notices that they were in violation of the law.

The ban on sledding took effect in the winter of 2001, along with a slew of other security restrictions. The rule is stern and unambiguous: "No person shall coast or slide a sled within Capitol Grounds."

Children, parents, and even D.C. Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton appealed to the compassion and common sense of Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Frank Larkin, who exhibited neither. "For security reasons," he replied , "the Capitol grounds are not your typical neighborhood hill or playground."

Indeed, they are not. The United States Capitol, and its grounds, belong to the people. Its occupants are public servants. If American children can fairly lay claim to any hill on which to sled and play, surely it is Capitol Hill.

As for security reasons? The threat posed by the sleds and coasters is confined to bruised shins and the occasional broken limb. It does not extend to the safety of Congress. Perhaps that is why Larkin also cited a law dating back to 1876, obliging him "to prevent any portion of the Capitol Grounds and terraces from being used as playgrounds or otherwise, so far as may be necessary to protect the public property, turf and grass from destruction or injury."

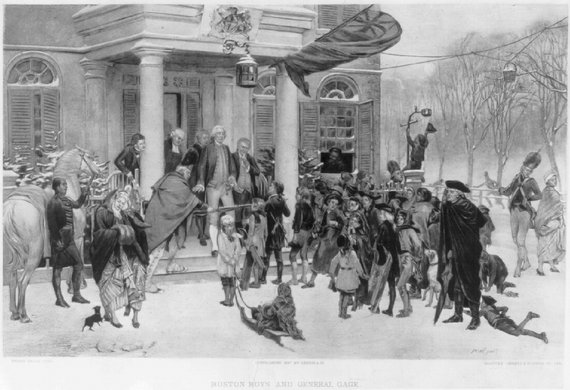

Henry Bacon/Library of Congress

But those rules were long honored only in the breech. In the early twentieth century, one local boy recalled , "the Capitol was our playground." Children had the run of the grounds, skated on the steps, and hid in the niches beneath the stairs. The turf and grass survived.

The inexorable extension of security perimeters has largely put an end to that. Official Washington is now a jumble of fences and cameras and magnetometers. Congress is no longer anyone's idea of a playground, except, perhaps, for lobbyists. Ordinary citizens are excluded from more and more of the buildings and facilities operated in their name, and at their expense.

Thursday was not the first time American children have confronted self-important security forces encroaching on their fun. Back in 1775, on the eve of the American Revolution, the schoolboys of Boston had to contend with the red-coated British soldiers quartered in their city.

Their favorite sled-run, carefully constructed each winter, ran from Sherburn's Hill down to School Street. It went directly past the residence of General Frederick Haldimand, whose servant deemed the slick, packed snow a threat to his safety. He scattered hot ashes, melting the sled run, ignoring the protests and pleas of the boys, and spoiling the route.

Then, as now, the children decided to protest. The boys elected a committee, and dispatched it to wait upon the general. Met at the door by his servant, they insisted on speaking with the general himself. The chairman of the committee laid out their case, as the astonished general listened. They, and their fathers before them, had used the land as a sled run, the boys explained. Reason carried the day. The general ordered his servant to fix the damage.

Later that night, Haldimand dined with General Gage, the colonial governor. He told the story of this remarkable encounter. Gage replied that the children had "caught the spirit of the times." They were willing to stand up to the British Army, demanding recognition of their traditional liberties, just like their parents. "What was bred in the bone," Gage said, "would creep out in the flesh."

It was the arrogance of the security forces, above all, that rankled the people of Boston. Other colonists were equally determined not to live in a country in which the forces charged with protecting them could shoulder them aside at will, a decision they later ratified in the form of the Third Amendment .

Thursday's protest was a small act, but it stands in that grand tradition. The story of the sledding children was retold for years after the event, because their defense of freedom illustrated a broader truth about Americans. "It was impossible to beat the notion of Liberty out of the people," General Gage reportedly mused about the sledders, "as it was rooted in ’em from their Childhood."

On Thursday, the kids gleefully sliding down Capitol Hill proved him right.