How Mass Surveillance During the Drug War Helped Justify Spying on Citizens

How justification for programs during the war on drugs turned into rationalization for spying on citizens in the war on terror.

It's been a long 22 months since the first of thousands of classified government documents became public in what has turned into a drumbeat of astonishing revelations about the scope of mass surveillance carried out by the United States government.

On Tuesday evening, USA Today detailed a massive surveillance operation, run by the intelligence arm of the Drug Enforcement Agency, that began in 1992. The DEA revealed the existence of the now-discontinued program back in January, and USA Today 's account offers remarkable details about how it worked.

The program, which enabled the United States to secretly track billions of phone calls made by millions of U.S. citizens over a period of decades, was a blueprint for the NSA surveillance that would come after it, with similarities too close to be coincidental, according to USA Today . Officials didn't collect the content of Americans' calls, the newspaper reports, but it gathered extensive data that enabled agents to stitch together detailed communications records and "link them to troves of other police and intelligence data" from the FBI, Customs, and other agencies.

The latest details are striking, not only because they reveal new depths of secret government surveillance, but also for how they reveal a continuum from the pre-9/11 War on Drugs to the post-9/11 War on Terror. That connection emerged almost immediately after the terrorist attacks—and it wasn't just rhetorical, it was literal: "Since the start of their bombing campaign [in Afghanistan]," The New York Times wrote in November 2001, "allied officials have tried to link the new war on terror to the old war on drugs." Taxes on poppy farmers who supplied Afghanistan's opium trade helped finance terrorist groups, the newspaper reported at the time.

Since then, both wars have become political shorthand. Both are brutally expensive and arguably un-winnable. And in both cases, use of the word "war" is a deliberate and calculated language choice. Americans are taught that a war is something an entire nation must fight, and something that requires sacrifice for the greater good. Considered in the context of government surveillance, both "wars" are euphemisms for a specific kind of government rationalization.

“The government has repeatedly tried to justify its spying activities on national security grounds, but it turns out it was doing much the same thing for years in aid of ordinary criminal investigations," said the ACLU attorney Patrick Toomey in an email via a spokesperson Tuesday night. "These new revelations are a reminder of how little we still know about the government's surveillance activities—including dragnet programs that operated for decades in secret."

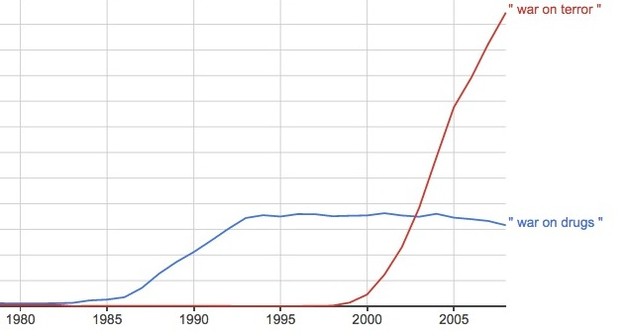

We might actually be able to pinpoint the moment—sometime in 2002—when the rhetoric switched from "drugs" to "terror" as a reason officials gave to citizens who might question their actions. Take a look at Google's count of published incidences of the phrase "war on drugs" versus published incidences of the phrase "war on terror" over a 50-year period.

Published Incidences of the Phrases 'War on Terror' and 'War on Drugs' Over a 50-Year Period

It's clear now that officials looked to their surveillance tactics in the 1990s as a playbook for how to carry out—and, crucially, how to legally justify—mass surveillance after 9/11. From USA Today :

Both operations relied on an expansive interpretation of the word "relevant," for example—one that allowed the government to collect vast amounts of information on the premise that some tiny fraction of it would be useful to investigators. Both used similar internal safeguards, requiring analysts to certify that they had 'reasonable articulable suspicion'—a comparatively low legal threshold—that a phone number was linked to a drug or intelligence case before they could query the records.

And in both cases, government officials—first with the DEA and later with the NSA—coerced technology companies to share data about their customers, sometimes even paying them for information. In most cases, they didn't push back. None challenged subpoenas in court, USA Today reported.

But while the NSA queried its secret phone databases hundreds of times in a given year, DEA analysts "routinely performed that many searches in a day," USA Today found. Over a two-decade period, the DEA and the Justice Department used Pentagon-installed supercomputers to log "virtually all telephone calls from the USA to as many as 116 countries"—the majority of countries recognized by the United States—including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Italy, Canada, Mexico, most of the countries in Central and South America and the Caribbean, plus other countries in western Africa, Asia, and Europe.

"It has been apparent for a long time in both the law enforcement and intelligence worlds that there is a tremendous value and need to collect certain metadata to support legitimate investigations," USA Today quoted George Terwilliger III, the former deputy attorney general, as having said.

Legitimacy, though, is a matter of debate. The government apparently took painstaking measures to keep its actions secret. The DEA was careful to keep the data it gathered out of criminal prosecutions so the program could continue without the public knowing about it. The DEA trained its agents to conceal from judges and defense lawyers the source of their intelligence.

Mark Rumold, an attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said the government will have a tough time making the case that the DEA program was legal. "Whatever constitutional wiggle room that might exist in the national security context vanishes when the surveillance program is aimed at enforcement of domestic criminal laws, like drug trafficking laws," he told me.

The ACLU is seeking documents related to the DEA's bulk collection of Americans' phone records under a Freedom of Information Act request ("nothing received so far," a spokesman told me Tuesday night). In the meantime, the drumbeat of information about government tracking of American citizens carries on.

"The government short-circuited any debate about the legality and wisdom of putting the call records of millions of innocent people in the hands of the DEA," Toomey said. "This pattern of extreme executive secrecy must come to an end."

NEXT STORY: CEOs Need Mentors Too