g-stockstudio/Shutterstock.com

There Really Are More Pregnant Women at the Office

In the past fifty years, more Americans have decided to work during pregnancy.

The case of UPS driver Peggy Young , which was decided by the Supreme Court two weeks ago, highlighted the issue of pregnancy discrimination in the workplace. Pregnant women often face latent discrimination and unfriendly workplace policies—Young's employer wouldn't lighten her workload when she was pregnant—but federal agencies are taking note. Complaints to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) about pregnancy discrimination have steadily risen in the last two decades, and just last year thethe EEOC issued new guidelines on the problem for the first time in 30 years.

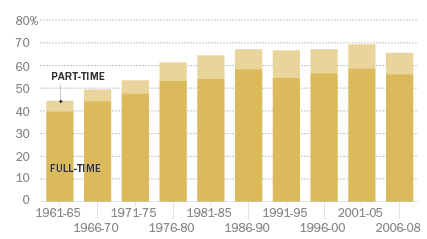

These developments are crucial given that, as a report from Pew Research (based on Census data ) shows, working while pregnant is increasingly popular. In the early 1960s, the percentage of women having their first child who had ever worked for six months was only 60 percent. That number has increased to 72.3 percent within the last decade. And the percentage of women working full-time during pregnancy has jumped from 40 percent in the early 1960s to 56 percent in the late aughts, with that figure for part-time workers jumping from 5 percent to 10 percent.

Percentage of Women Who Worked During Pregnancy

The Pew report also found that women are working longer into their pregnancies. 82 percent of female workers pregnant with their first child continued to go to work until they were within one month of their due date. The labor-force participation rate of women who have given birth in the last 12 months is at an all-time high of above 60 percent; that number was just 17 percent in the early 1960s .

So what are the outcomes of a workforce increasingly involving pregnant women? International data gives a blurry picture of whether the number of weeks of paid leave has any connection to a country's gender pay gap. But one thing is certain: Having as many women in the workforce as men is estimated to bring a 5 percent increase for America's GDP , and studies have shown that working (especially full-time) during pregnancy both increases the likelihood of a mother returning to work and of that return being sooner.

Another proposed way to get women back to the workforce after having a baby is universal childcare, as costs in the U.S. become untenable for many families . Research has shown that providing women with incentives, such as universal childcare, to return to their jobs after having a baby can yield tremendous results. In Quebec, up to 86 percent of mothers are in the workforce , the highest rate in Canada. Economists estimate that the province's policy to provide universal access to cheap childcare induced 70,000 more mothers to hold onto their jobs after giving birth and increased Quebec's GDP by nearly 2 percent.

Hopefully, these changes will be accompanied by shifts in attitude, in that pregnant workers might provide inspiration to other women in the workplace . Having more pregnant women in the workplace will hopefully help to shatter norms that reinforce discrimination, and maybe in another 20 years no one will think it's weird that a woman is choosing to work until two weeks before her due date.

( Top image via g-stockstudio / Shutterstock.com )