The museum construction site in October 2014. Dorian Shy/Smithsonian Institution

9 Things You Need to Know About the National Mall's Newest Museum

When it finally opens its doors, the National Museum of African American History and Culture will be one of the most contradictory institutions on the National Mall.

Ten years ago, the National Museum of African American History and Culture had a staff of two. There was no site locked down for the building. No design attached to it. And no stuff to put in it.

"We knew we were going to have to raise millions of dollars, but we didn't have a penny to our name," said Lonnie G. Bunch III, the museum’s director since 2005, during a press conference this week. ”And also, unlike most museums, we didn’t have a single artifact in our collection.”

The latest addition to the National Mall is, as Bunch put it, “Ten years in the making, and 100 years in the making.” Today, the National Museum of African American History and Culture already employs 120 full-time staffers. Its collection numbers around 33,000 artworks and historical objects. And the museum’s leadership has raised nearly $476 million in public and private funds.

Still, the Museum—that’s what NMAAHC staffers call it, “The Museum”—lacks a concrete opening date. A press conference held Thursday to introduce the new museum fell just shy of a hard-hat tour. While construction crews are working day-in and day-out, the building is unfinished and behind schedule.

Nevermind, Bunch said. There’s no question: It will open in fall 2016, and there’s a reason for that.

“This museum will be opened by President Barack Obama,” he told reporters. “That you can go to the bank on.”

When it does open its doors, the National Museum of African American History and Culture will be one of the most contradictory institutions on the National Mall. The history told by the museum is marked by moments of sweeping uplift and achievement, yet it’s framed by the wickedness of institutional terrorism. Its narrative is particular to a single proud people, but at the same time this history is core to every American’s experience, whether they recognize it or not.

“[The museum] continues to grapple with the question: What is real freedom?” said Rex Ellis, associate director for curatorial affairs, during the presentation. “It takes more than a document. It takes more than a formal piece of paper.”

The museum is not quite ready for a close look just yet. But here are some facts about the building, its collection, and its curators that make it a stand-out even now, 18 months from being finished—give or take.

The Museum Borrowed a Page From Antiques Roadshow

a rendering for the National Museum of African American History and Culture (Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup)

A decade in, the museum has amassed a striking collection. It owns a Jim Crow–era segregated railcar that viewers will be able to walk through to experience first-hand. It owns shards of stained glass from the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing (which are harrowing to see even in a slideshow). The museum owns a Hymn book carried by Harriet Tubman that dates back to 1876—surely a sacred object without peer in most collections.

When the museum acquired the Mothership—the funkdafied flying object that George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic used as a stage prop for their concerts—the Dogfather of Funk himself told The Washington Post, "I'm about to cry!" And of the 1973 candy apple–red convertible once owned by Chuck Berry, Bunch said, “There are stories we probably can’t tell about that Cadillac.”

Acquiring the popular history that’s well-known is one thing. Building the history that’s still invisible is another story, and another part of the contradiction of the museum. “So much of our heritage is still in the basements, attics, and trunks of people’s homes,” Bunch said.

So to discover those stories, starting in 2008, museum conservators and historians set out on a tour. “Save Our African American Treasures” has traveled from Chicago to Charleston, Atlanta, Topeka, Dallas, Houston, and a host of other cities since. The museum “borrowed” the idea from the PBS seriesAntiques Roadshow, according to the director.

The Museum Is Divided Into 10 Major Galleries

Richard Ansdell, The Hunted Slaves, 1862. (National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Ellis explained in some detail how the galleries will unfold in the history and culture sections of the museum. “Community” is a third chapter heading.

This is just a brief summary of how those galleries will be organized thematically (along with the curators primarily responsible for them), but it gives a sense of the flow of the museum.

History Galleries

- Slavery and Freedom (curator: Nancy Bercaw)

- Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom: Era of Segregation (1876–1968) (curator: Spencer Crew)

- A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond (curators: William Pretzer and Michelle Wilkinson)

Culture Galleries

- Musical Crossroads (curator: Dwandalyn Reece)

- Cultural Expressions (curator: Joanne Hyppolite)

- Visual Arts Gallery (curators: Tuliza Fleming and Jacquelyn Serwer)

Community Galleries

- Power of Place (curator: Paul Gardullo)

- Making a Way Out of No Way (curators: Michèle Gates Moresi and Kathleen Kendrick)

- Sports Gallery (curator: Damion Thomas)

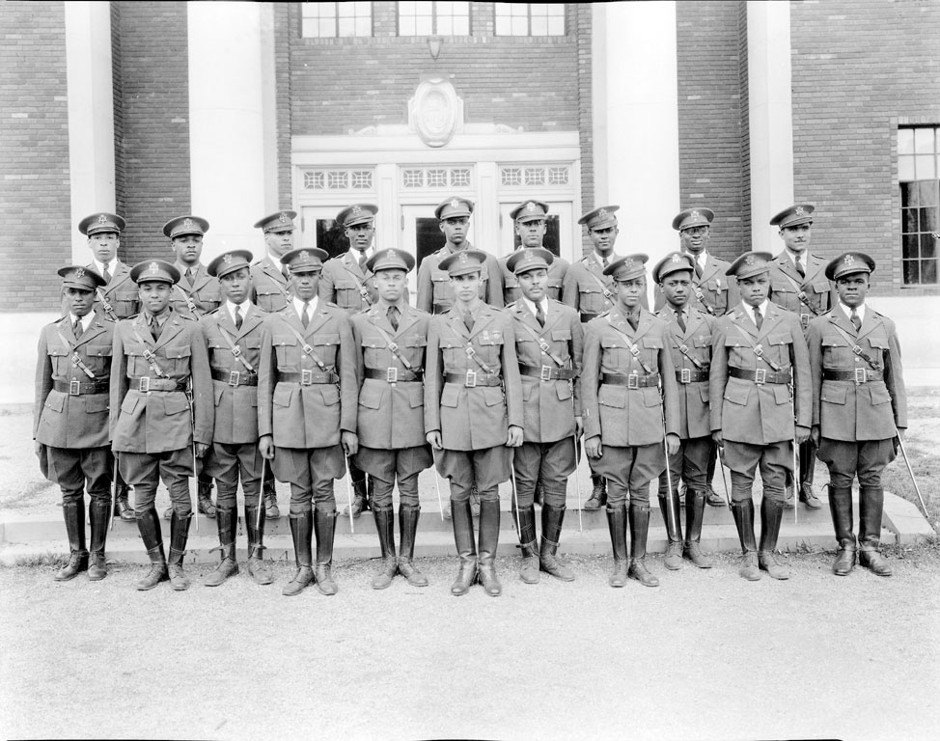

- Military History Gallery (guest curator: Krewasky Salter)

Ellis took pains to say that the culture galleries would not be mere halls of awards and paraphernalia. The Sports Gallery, he said, “is about how [athletes] used that gift that they had to look at the social and political and economic realities that they lived under,” for example. The Military History Gallery concerns the black soldiers who fought for freedom, thinking that would make them free.

From a glance—really, just renderings in a slideshow, which is not much to judge by—it looked as though some galleries leaned heavily on digital kiosks and touch-screen tables. This has been a problem with two new Smithsonian galleries at the National Museum of Natural History (the Human Origins wingand the Sant Ocean Hall).

But it’s way too early to judge the National Museum of African American History and Culture on this score. These galleries don’t exist yet.

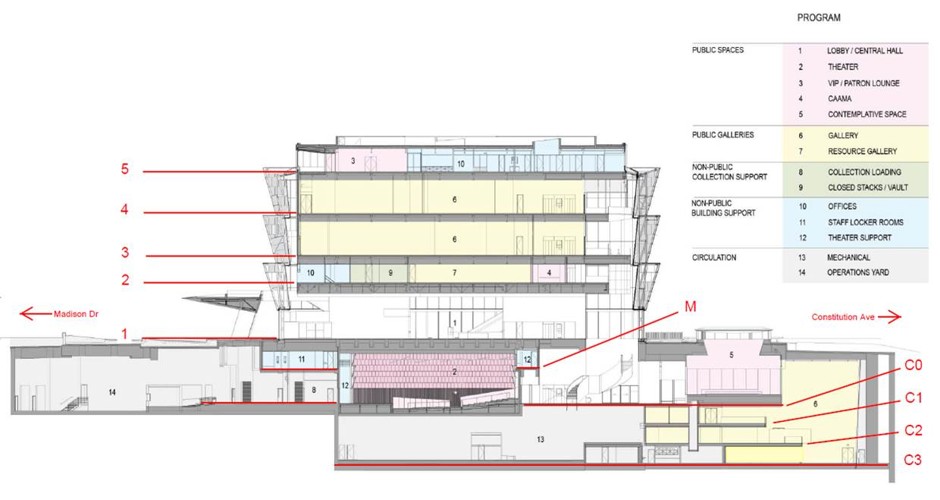

There’s As Much Museum Below Ground as Above Ground

Forty percent of the museum’s programming will be found in the five stories that rise above ground. But 60 percent of the 400,000-square-foot building is actually below grade. The National Museum of African American History and Culture rises five stories up and plunges five stories down.

The museum will encourage viewers to start at the bottom, in the history section, then travel upward via a grand staircase into the culture galleries. But the linear format isn’t the only way to see the museum.

“One of the things Dr. Bunch always wanted to do with the museum was have this freedom so you could explore multiple levels in any kind of sequence,” said Robert Anderson, director of the D.C. office for Davis Brody Bond, during a visit to the construction site.

Incidentally, the design team is Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup, comprising architects from the Freelon Group (Research Triangle, North Carolina), Adjaye Associates (London), and Davis Brody Bond (New York and D.C.), with engineers from SmithGroup (D.C.).

Cross-section of the museum. (NMAAHC/Smithsonian Institution)

Lonnie Bunch Has One of the Sweetest Offices in D.C.

Refer back to the diagram. See the space for offices? The museum director’s corner office has a straight line of sight to the Lincoln Memorial. There’s no view from the Castle that’s as good. This isn’t worth anything more than a footnote, but it may be the nicest office across the entire Smithsonian Institution.

The Museum’s Bronze-Colored Wrapper Is Called the ‘Corona’

Workers install the panels to create the museum's “Corona.” (Eric Long/Smithsonian Institution)

Bunch said that he’s been greeted by one question more than almost any other: “Is this building going to look African American?"

The question is fascinating—and basically, the answer is yes. Bunch and Phil Freelon, one of the principal design architects, explained that the building’s façade is, in fact, a true tribute to black craftsmen.

The signature exterior feature—the metal screens enclosing the museum—is called the “Corona.” Each customized, bronze-colored, cast-aluminum panel (3,600 all in all) reflects the design of iron work by enslaved craftsmen in both Charleston and New Orleans.

The façade system weighs 230 tons, which is remarkable, since it’s essentially draped from the top of the building—not stacked, as it might physically appear. The panels come on a pre-assembled frame; the frames hang on a series of outriggers, which are the supports that give the exterior its sawtooth shape; and the outriggers are suspended from a belt-truss system joined to the fifth floor.

"It's a very simple, repetitive puzzle," said Anderson. "The biggest challenge is getting the right panels in the right locations, because different panels have different degrees of porosity."

Left: One of the mock-ups used to test the coloring and patina of the metal panels. Right: The backside of a panel

These panels accomplish several things at once. They prevent glare and heat gain inside the building. The “variegated transparency of the panels,” as Freelon put it, “privileges certain views” and obscures others—meaning that the size of the holes or apertures vary from panel to panel. The architects achieved this useful but complicated differential “porosity” using algorithmic design software.

The creative achievement may in fact overshadow the technical wizardry. This façade is both modern and narrative. It’s relevant. Bunch described the building as a “monument to the work of the people who made this country possible, but whose work is hidden in plain sight.”

The Theater Is Named After Oprah Winfrey

No surprise there: Oprah Winfrey has served on the advisory board of the National Museum of African American History and Culture since 2004, just a year after Congress passed the legislation creating the museum. She’s put at least $13 million toward the fundraising effort.

Individual donors like Oprah don’t make up the bulk of the museum’s funders, though. Congress paid 50 percent of the costs for the building and staff. Of private money raised, 43 percent came from corporate sources.

Here’s What the Museum Looks Like Today

Construction progress on May 7, 2015.

The Museum Has Already Mounted a Bunch of Exhibits

Back in 2009, I saw the very first exhibition put on by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “The Scurlock Studio and Black Washington: Picturing the Promise” showed at the National Museum of American History as a pop-up exhibit.

Unlike many shows, this one’s stayed with me ever since. “The Scurlock Studio” was a survey of more than 100 portraits by Addison Scurlock, a black portrait photographer who, in 1911, put out his shingle on U Street NW in Washington, D.C. (close to where I lived almost a century later). His sons, George and Robert Scurlock, kept the family business going until 1994. Anyone who was anyone in black middle-class D.C. (and beyond) had their picture taken by the Scurlocks.

That’s just one of the pop-up exhibitions that the National Museum of African American History and Culture has mounted. The museum presented “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty” with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation in 2012, a breakthrough exhibition.

Friday marks the opening of “Through the African American Lens: Selections from the Permanent Collection” at the National Museum of American History. The show includes, among other artifacts, the dresses that En Vogue wore in the video for “My Lovin’ (You’re Never Gonna Get It).” (What do you got, Hirshhorn Museum?)

Real-Time Curating Is One of the Museum’s Goals

The museum building hadn’t yet topped out when Michael Brown was shot and killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, last August. The nationwide protests that have erupted since then pose a different question for this museum than most. How will the National Museum of African American History and Culture account for the ongoing #BlackLivesMatter demonstrations?

The museum has already answered. To start, on April 25, the museum hosted an all-day symposium, “History, Rebellion, and Reconciliation,” featuring speakers such as Mychal Denzel Smith, Jasiri X, and Jamilah Lemieux. Once the museum opens, part of at least one gallery will touch on the protests.

Relive @NMAAHC's stirring & timely- History, Rebellion & Reconciliation symposium #HRRlive https://t.co/ywe8U3dWeQ #museumsrespondtoferguson

— LaTanya S. Autry (@artstuffmatters) May 4, 2015In a way, the National Museum of African American History and Culture already has in its collection the resources that will serve as context for any discussions about the value of black lives and black bodies: from a bill of sale, dated December 23, 1835, for a black girl named Polly ($600), to a 20-foot-tall prison guard tower once used to monitor inmates at the maximum-security Louisiana State Penitentiary.