“This is a process that is expected—you’re not opening some Pandora’s Box that’s been unheard of,” Fletcher said. “It shows maturity ... it shows confidence.”

Prasit Rodphan/Shutterstock.com

Graduation season—replete with lengthy ceremonies and their (sleep-inducing) commencement speakers—is in full swing. Across the country, recent grads have traded in their anxiety about getting their diplomas on time for new kind of stress: finding employment. And for the lucky ones

who actually land a good job

, new data suggests they’ll probably settle for far less money than they’re worth.

A recent study by the online financial resource

NerdWallet

, in conjunction with

Looksharp

, a job-search tool, shows that fresh-out-of-college students tend to become quite shy when negotiating their first salaries. The survey—which reflects responses from 8,000 recent grads and 700 employers—was conducted over a three-year period starting in 2012. It found that 62 percent of recent graduates didn’t negotiate their salary at all even though 75 percent of employers said they had room to bump of their original offer—and even though “most of them” expected to do so. The data also showed disparities based on gender and college major.

Salary negotiation is tough for anyone, regardless of age. ( The Atlantic even recently ran a Q&A with a hostage negotiator for advice on navigating salary deliberations.) But these fears are particularly widespread among recent college grads, perhaps because of the harsh economic climate . And many college students may be accustomed to unpaid or low-paying internships as a precursor to their first official job offer.

“They were just happy to have an offer, any offer,” said Abbey Stauffer, one of the analysts who worked on the study. “Any kind of money can seem like a lot after being a student for four years. They didn’t have much of a concept about how much the dollars on the page would translate to real life.”

The economic climate during the years covered by the survey certainly has its psychological effects. Most of the students featured in the survey would have entered school some time during the recession, which may have taken a toll on their perception of the job market. This is a group that’s been characterized as “ overeducated and unemployed ”—a.k.a., “ recession generation .” Compound that with the fear that an offer will be rescinded, the increasing cost of college, and the burden of student debt, and a perfect cocktail of uncertainty and doubt emerges.

Unemployment Rates for College Graduates

“They are just unaware that this opportunity is available to them and even if they are [aware] they lack the confidence to face these questions,” Stauffer said. “A lot of what we heard was ‘I didn't know that I could do it.’”

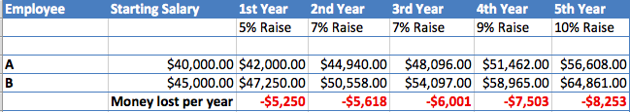

Meanwhile, a person’s first salary

is critical

: Missing out on an extra $5,000 that first year, for example, can really add up.

Potential Salary Lost Over Time

“You could be setting yourself up to be perpetually behind,” Stauffer said.

The survey found, perhaps unsurprisingly, that women were less likely to negotiate than men were.

Some of this could be attributed to deep-rooted gender roles, or the “

confidence gap

,” the theory that men are far more confident in the workplace than women are. But the exact reasons are complex, Stauffer said: “It could be from the instruction that those [female] students get from university staff, whether there are biases there. Or differences in how their parents have approached them along the way.”

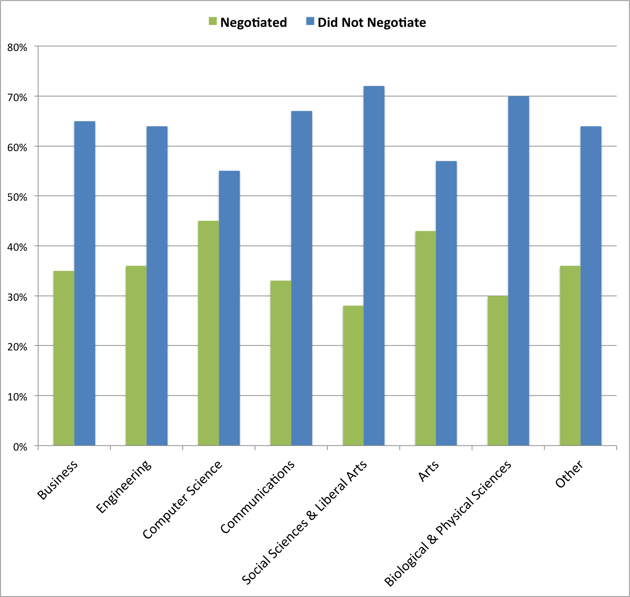

But there are caveats to the findings about gender. It turns out this confidence gap isn’t as prevalent in certain industries. For example, according to the study, women entering the computer-science field—in which they are

traditionally underrepresented

—were generally more likely to negotiate than women in other fields.

Percentage of Women Who Negotiated Salary, by Industry

“They are thinking, ‘I know that I am sought after and I have leverage,’” Stauffer suggested.

Regardless of the gender disparities, the data suggests colleges’ career centers could do more to prepare students for salary negotiation, according to David Fletcher, the career advisor at American University. “We spend a lot of time with the other facets: Resumés, cover letters, interview prep, job fairs,” he said. “But I don't think there is enough emphasis on salary negotiation.”

But perhaps that’s largely because of the timing of many employment offers, which often occur in either the weeks immediately preceding or proceeding graduation. Some career centers are closed during the summers, and students may not know that the ones that are year-round are available, Fletcher said.

The survey also asked employers about their thoughts on salary negotiations.

As the data shows, inquiring about a salary increase is rarely a game-changer.

“They should always ask ... Employers work very hard to identify a strong candidate—the last thing they are going to do is toss out a top candidate because someone wanted a few thousand dollars more,” Fletcher said. “An HR person has all the leverage … up until they make that salary offer.”

Some employers were even surprised that the topic never came up.

( Image via Prasit Rodphan / Shutterstock.com )