Flickr user Tim Evanson

Can HUD's New Rule Fix Residential Segregation?

The Obama administration issues a new rule—and a mapping tool—that are designed to help communities address segregation.

Ever since the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the federal government has been obligated to try and foster inclusive, diverse communities. In practice, that means moving poor, black families into richer, white neighborhoods and providing grants for improving areas of concentrated poverty.

But for decades, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, has fallen short of these goals, and at times its efforts have even backfired,perpetuating patterns of segregation by building more housing for America’s poorest in America’s poorest neighborhoods. Deep racial and economic segregation continues to dictate where Americans live.

“One of the problems with the failure to really give this statutory provision meaning and teeth up until now is that people could pretend it didn’t mean anything, and failure to comply with it didn’t have consequences,” said Betsy Julian, the president of Inclusive Communities Project, a Dallas non-profit that recently won a Supreme Court case protecting parts of the Fair Housing Act. (Julian also served as HUD’s Assistant Secretary for Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity in the Clinton Administration.)

On Wednesday, HUD took a big step toward fixing its own ineffectiveness, releasing a new rule that requires that cities and regions evaluate the presence of fair housing in their communities, submit reports detailing the presence of segregation and blight, and detail what they plan to do about it. Communities will be required to hold meetings or otherwise solicit public opinion about housing planning and integration every five years, and will have a new trove of resources to assess their progress.

“This important step will give local leaders the tools they need to provide all Americans with access to safe, affordable housing in communities that are rich with opportunity,” said HUD Secretary Julian Castro.

Parts of the new rule will take effect in 30 days.

By law, communities are expected to affirmatively further fair housing through the way they use federal funds, including Community Development Block Grants (used for a variety of development initiatives), public-housing-authority programs such as Housing Choice Vouchers and housing complexes, and HOME grants, which fund the development of affordable housing.

But the law previously only required that, to get these funds, communities certify that they have a document called an Analysis of Impediments outlining why people could not find affordable housing, and that they are taking actions to overcome these impediments. Many communities don’t update their Analysis of Impediments, though; a 2010 GAO report found that some grant recipients didn’t have a document at all, and in other communities, the reports were from the 1990s.

The new rule replaces this process with a tool that allows participants to assess fair housing issues in their communities with the aid of data provided by HUD. Cities, regions, or housing authorities will submit a document called an Assessment of Fair Housing to HUD, which will review and accept the document. That document will analyze integration patterns and disparities in access to high-quality affordable housing, and will include input from the community on what to do about it. HUD can choose to reject parts of a community’s Assessment of Fair Housing if it determines that that plan is incomplete or is inconsistent with fair-housing laws.

This may all just sound like a change in the way housing authorities do their paperwork, but for housing advocates, this is a big deal.

“This is going to be an incredibly important and positive step to changing things over the long run,” said Ed Gramlich, a special advisor to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Previously, there had been no definition of what, exactly, an impediment to fair housing is, and what communities should do about it. The county of Westchester, in New York, for example, took millions of dollars of federal housing money andclaimed to comply with fair-housing mandates. It signed a consent decree in 2009 to settle a lawsuit about this, but still has not taken any steps to comply with fair-housing laws, and the county executive there has spoken publicly about his opposition to integration.

Now, HUD will be hopefully able to spot such misuses of funds before the money is spent. Jurisdictions have guidance for how they can “affirmatively further fair housing,” and administrations that want to enforce the Fair Housing Act have more tools at their disposal.

The tools and data that jurisdictions will use to figure out whether they are promoting fair housing are the “centerpiece” of the new rule, according to the Washington Post’s Emily Badger.

“The premise of the rule is that all of this mapped data will make hidden barriers visible—and that once communities see them, they will be much harder to ignore,” she writes.

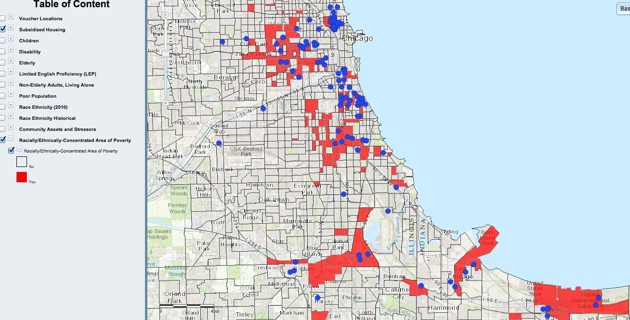

The mapping tool will include data about housing, voucher locations, subsidized housing, income, limited income proficiency and other factors. A prototype of that map, released last year, is a stark reminder of the segregation that exists across the country today.

The new rule comes on the heels of the Inclusive Communities decision by the Supreme Court, in which the Court ruled, 5-4, that housing policies that have a disparate impact on minority populations are illegal, whether or not discrimination is present. Disparate impact is a separate issue than policies that “affirmatively further fair housing,” but both concern what the law has to say about integration and fairness in the nation’s housing stock.

Taken together, said Julian, of Inclusive Communities, the new HUD rule and the Supreme Court decision require public entities that administer federal funds to take a hard look at whether their programs are working to integrate their residents..

These entities don’t just include HUD—they also include states that distribute Low Income Housing Tax Credits, which were the subject of the Supreme Court case, as well as transportation entities that administer urban development funds and city housing authorities that build in urban and suburban areas.

They’ll have to look at whether “those programs have been operating with the effect of perpetuating segregation, containing people in neighborhoods and communities marked by conditions of slum and blight, and excluding people from well-resourced neighborhoods and communities,” she said.

The new rule makes communities look at their segregation and poverty patterns, Julian said, while at the same time holding them accountable for remedying them. That was the goal of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Now, it might just begin to happen.

“The imperative to appropriately address those conditions of distress becomes a civil rights and fair housing imperative, not just a feel good community development policy,” she said.(Top image via Flickr user Tim Evanson)