LoloStock/Shutterstock.com

Exposing Organizations That Pay Women Less Than Men

How the British government is addressing a global problem.

It’s often considered gauche to ask people about their salaries, but the British government is planning to do just that. In a bid to combat the gender pay gap, Prime Minister David Cameron announced on Tuesday that his government will institute a measure requiring companies with more than 250 employees to publicly disclose information on the average pay of their male and female workers. The move, the prime minister hopes, “will cast sunlight on the discrepancies and create the pressure we need for change, driving women’s wages up.” Some critics believe he’s overestimating the power of that sunlight—and underestimating the structural inequities behind such discrepancies in the workplace.

The regulations, which were passed in March but initially opposed by Cameron’s Conservative Party, will now be subject to public consultation until September. The consultation will determine “exactly what, where, and when information should be published,” and the government is “working closely with business and others to find the most workable and effective way of implementing the regulations,” according to a British Embassy spokesperson. The legislation won’t come into force until October 2016 at the earliest.

It’s a British solution to a global problem. There are many different ways to measure the pay gap between genders, leading some to even assert that the whole concept is a myth. But official statistics from a variety of sources suggest that women’s compensation continues to lag significantly behind men’s around the world.

In the United States, for instance, women earn less than men who work in the same field and have the same academic qualifications, according to a 2013 congressional report. In their first year of work after getting a bachelor’s degree, women make roughly $7,600 less per year than men. These wage discrepancies often persist throughout a woman’s career and make it harder for women to pay off student loans (which women are more likely to have, and to have more of) and save for retirement. Closing the pay gap wouldn’t just help create a fairer society and workplace; it could also halve the poverty rate for working women in the United States, according to the Center for American Progress.

In the United Kingdom, meanwhile, the pay gap—as measured by the difference between men’s and women’s hourly earnings as a percentage of men’s earnings—is at just under 10 percent for full-time employees and just under 20 percent for all employees, according to a 2014 report by the Office for National Statistics. That puts the U.K. in the bottom quartile for gender wage equality in the European Union. A 2014 World Economic Forum (WEF) report, which takes a more global view, places the U.K. at 48 out of 131 countries on gender pay equity; by comparison, the United States is ranked 65th. The most equitable country in this regard? The small East African nation of Burundi.

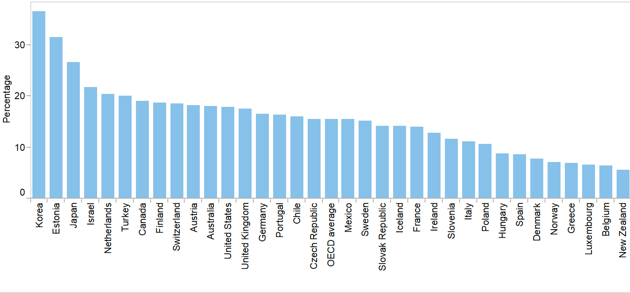

Here’s how the wage gap between men and women in the U.S. and U.K. compares with those in other countries within the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The gap is largest in South Korea and smallest in New Zealand.

Gender Wage Gap by OECD Country

Britain’s new approach to this challenge isn’t entirely novel among its neighbors in Europe, according to a breakdown of the continent’s policies by Shirley Wright of the British law firm Eversheds LLP. The Swedish government requires employers to carry out (but not publish) a pay survey every three years; if unjustifiable pay differences between genders are found, the differences must be remedied within another three years. The Austrian government mandates an annual gender pay report for all companies with 150 employees or more, with the findings occasionally shared with employees. In Denmark, employers must discuss gender pay audits with employees. In Belgium, firms are required to include gender wage differences in annual audits, and companies with more than 50 employees must draft a plan of action when a pay differential is discovered. Federal contractors in the United States are required to monitor and report data on compensation by gender to the Department of Labor, but there are no such requirements for the private sector as a whole.

It’s not always clear how effective these innovative policies are, but the good news is that in much of the world, the pay gap between men and women is slowly shrinking. Still, the emphasis should be on the word “slowly.” According to the United Nations, it will take 70 years to close the gender gap in pay around the world. That’s over half a century more of less income, less savings, and less dignity. Sunlight only moves so quickly, and reaches so far.

(Image via LoloStock/Shutterstock.com)