Obama and Biden speak with a solar company official in 2009 amongst solar panels. Pete Souza/White House file photo

How Will Obama's Clean Power Plan Affect Low-Income and Minority Communities?

A significant chunk of the plan focuses on “community involvement and environmental justice.”

President Obama’s formal announcement Monday of his finalized Clean Power Plan puts the responsibility on states to come up with their own strategies for reducing climate pollution. But states are already charged with monitoring and mitigating air pollution flowing from their borders, which hasn’t always boded well for cities and the communities residing close to pollution-heavy facilities. Which is why it may be relieving for many families to know that a significant chunk of the Clean Power Plan focuses on “community involvement and environmental justice.” From a White House fact sheet on the plan:

The White House

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the federal principal custodian of the Clean Power Plan, has also pledged to conduct air quality evaluations in neighborhoods that have historically been saturated with both pollution and poverty. Still, it remains to be seen how much of a venue such neighborhoods—which are often predominantly African-American and Latino—will be granted to air out their problems with the state.

In the lead up to the plan’s unveiling, environmental and civil right advocates were already concerned with this issue. Here’s how the NAACP’s environmental and climate justice program director, Jacqueline Patterson, put it on a conference call Monday:

In the period between the release of the proposed Clean Power Plan and today’s release of the final plan, we have been pushing for reform from what was originally proposed, including stringent [environmental justice] analysis and mandatory engagement of oft-marginalized communities in the state implementation plan design and decision making. We also expressed concerns about the fact that the proposed plan included credit being given for still hazardous practices, including use of nuclear energy, natural gas, biomass, and carbon capture and sequestration which fails to address the cradle to grave dangers of coal.

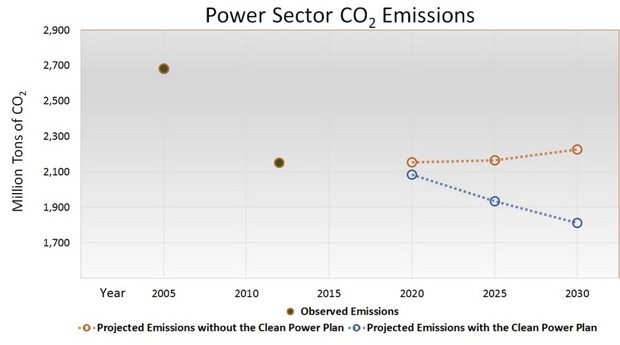

In other words, advocates like Patterson want to be sure that states won’t find yet more ways to concentrate pollution in already over-burdened neighborhoods. The Clean Power Plan calls for a 32 percent decrease in carbon pollution (based on 2005 levels) across the nation. Each state has its own unique target for carbon reduction based on how it produces energy. Up to this point, some states have clustered their polluting facilities in vulnerable, “fenceline” communities—low-income, often minority neighborhoods situated close to the bordering fences around power plants—as seen in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley” and the east end of Texas.

EPA

There’s no telling how robust each state’s public participation processes will be until they begin hammering out plans. And climate justice won’t exactly be delivered swiftly here, given that states have until as late as 2022 to implement plans—a two-year extension on the originally proposed start date. If the plan survives legal challenges and states comply, EPA anticipates other benefits beyond taming climate change, like preventing 90,000 asthma attacks and 300,000 missed work and school days annually.

“As we turn to the state implementation plan processes, we must establish aggressive targets for climate action including emphasizing community engagement, ramping up pollution reduction for each plant,” said Patterson, “and significantly increase our focus and action on energy efficiency and clean energy—meaning solar, wind, geothermal, and ocean energy—while creating good jobs.”

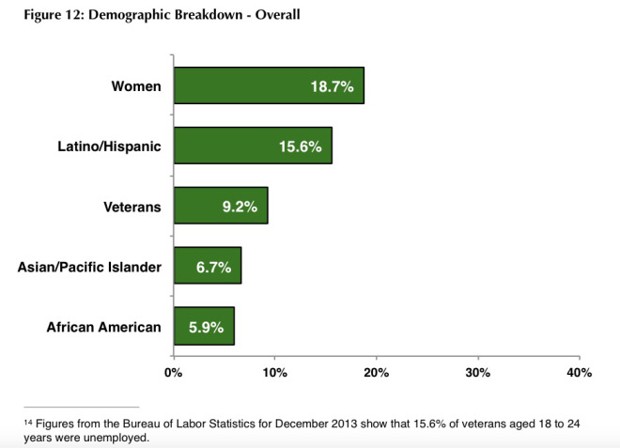

Jobs are another huge part of the equity factor that civil rights groups like the NAACP are seeking. The solar industry is taking off, creating jobs at a much more accelerated pace than the oil and gas industry. But African Americans represent the smallest portion of the solar labor force.

Solar Foundation

There’s also the concern that low-income families and renters haven’t been enjoying the same access to solar power for their homes, which can reduce electricity bills. The Clean Power Plan includes a new measure that credits states for developing energy efficiency programs for low-income communities. It also features a new Clean Energy Incentive Program, which will reward early investments made in wind and solar generation. But there’s nothing explicit in the plan that incentivizes renewable energy programs specifically for low-wage earners. President Obama is addressing this separately in a program he announced last month that will deliver solar power to renters and 300 megawatts of renewable energy to public housing by 2020.

Another snag spotted by environmental justice advocates: The EPA is allowing, in fact encouraging states and power plants to reduce carbon pollution by emissions trading, aka “cap and trade.” In such market-based trading programs, companies can obtain pollution allowances from other firms that have found ways to reduce their own pollution load, say by converting a coal plant into a solar farm. In similar trading schemes, firms can obtain additional pollution allowances by paying for environmentally friendly projects in other places, or “offsets”—a scheme that has already caused some controversy in California.

Environmental justice advocates say that such programs lead to inequities by letting companies continue to pollute as long as they can afford to purchase allowances, which provides no relief for families living near plants. Under the Clean Power Plan, states and companies that choose to utilize trading programs would still have an overall cap on how much carbon pollution they can emit annually. But the family living next to a coal plant that can continue polluting thanks to purchasing additional allowances would suffer, unlike a family living next to a power plant that has converted to solar. This could prove problematic for communities in states where coal companies dominate the economy, and have no desire to change that.

Civil rights groups have the next seven years to work with states on how to implement a trading system in more equitable ways. EPA, meanwhile, hasn’t been super responsive to civil rights concerns, as a Center for Public Integrity report released Monday revealed.

Fortunately, there are a few models for states to consider in pursuing equity factors in the Clean Power Plan roll-out. Last month, New York’s public service commission created new renewable energy policies that give renters better access to solar-sourced electricity and prioritize energy projects where at least 20 percent of benefactors are low-wage earners. And the aforementioned cap-and-trade program in California requires that 25 percent of revenue from emissions trading goes to assisting low-income communities. The 2012 report “Facing the Climate Gap,” from the University of Southern California’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity, lists a number of other models for incorporating racial and economic equity while pursuing climate change reduction goals.

At a ceremony yesterday announcing the new Clean Power Plan, President Obama said he already anticipated the opposition’s arguments, namely that it will hurt the economy and kill jobs.

“Even more cynical,” said Obama, “we’ve got critics of this plan who are actually claiming it will hurt minorities and low-income communities, even though climate change hurts those Americans the most. … So if you care about minority, low-income communities, start protecting the air that they breathe.”

It registered his longest ovation during his speech.