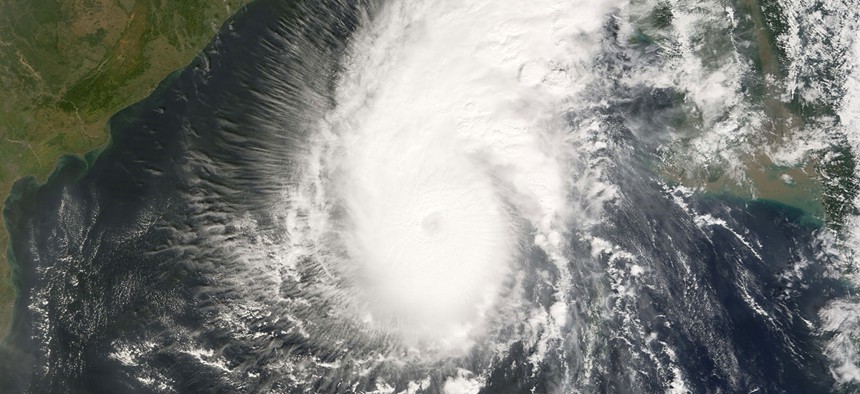

NASA's satellites capture images of weather events like 2007's Tropical Cyclone Sidr. NASA file photo

NASA Data From Space Could Help the Developing World Prepare for Climate Change

The agency’s satellites have a unique vantage point.

When we think of NASA, we think of deep-space exploration. We expect the agency to be working on questions like what life would be like on Mars or how to build a city on the moon. But researchers—and astronauts—have been on another kind of mission: to bring space down to Earth and to the developing world.

In 2003, the agency teamed up with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to form SERVIR, an initiative to use data gathered in space to help developing countries combat problems arising from climate change. Its name comes from the Spanish word meaning “to serve.”

The satellites that NASA launched years ago for research are now sending back information that can help Kenyan farmers protect their crops from frost, Nepalese officials monitor forest fires, and policymakers in Botswana prevent land degradation. The projects, which are active in more than 30 countries around the globe, are based on extensive needs assessments conducted by USAID. And the satellite data doesn’t replace on-ground monitoring; rather it serves as an additional resource.

In Bangladesh, for example, NASA has been helping cities prepare for floods up to eight days in advance. The country—with its low elevation and tropical storms—sits at the mouth of the Ganges river and is prone to severe flooding come monsoon season. In places like the capital Dhaka, the world’s densest city with more than 14 million people, floods have the potential to displace tens of thousands every year. The cities rely heavily on warning systems, which predict how high the water level will rise based on how much rainfall the country gets and which way the water flows.

“But Ganges and Brahmaputra [river basin] is not only in Bangladesh; it extends into India, Nepal, and China,” says Ashutosh Limaye, project scientist for SERVIR. “So if those countries don’t share their water data, then Bangladesh cannot predict when the flood might come.”

That’s where Jason-2, NASA’s satellite launched in 2008 to study the ocean’s topography, comes into play. “Anybody can look at that NASA data … and figure out what the changes of water level are and deduce if there is a flood wave coming from India, even though India doesn’t share its data,” he continues. “So you can extend that forecasting window.” And for a densely populated country, those extra few days means more time to get millions, particularly those living along the coast, onto higher ground.

A map showing the thousands of images captured by NASA’s satellites, which can be used to help countries fight climate change. (SERVIR)

In another example, NASA is using satellite imagery of vegetation health, or “greenness,” and real-time rainfall measurements to help East African countries monitor for potential crop failures. That way, policymakers know if they have enough food to feed the population or if they have to import grains from outside markets months in advance, before prices start to peak.

“What makes the relationship [between NASA and USAID] so important is that it’s two very, very different agencies that have come together,” says Dan Irwin,program manager of SERVIR. “It’s something that not one agency can do alone.”

Indeed, bringing new technology into developing countries has its set of own challenges. “It’s not like you can just say, ‘We’ve done it,’ and throw it over the fence and say, ‘Here you go,’” Irwin tells CityLab.

Limaye adds: “Convincing them [to use] these additional data sets is a bit of a challenge because you’re challenging the status quo.”

It involves working with USAID, ministries, non-governmental agencies, and “regional hubs” made up of locals to train people on how to use the data and to help policymakers understand the benefits of using satellite data. And that can get difficult, especially when governments have high turnover rates. “I can’t emphasize this enough, but these regional hubs are where rubber meets the road,” says Irwin.

He adds that extending a hand—or in this case, satellites, maps, and data gathered from space—has always been part of the agency’s broader goal: “to travel into space and use that unique vantage point to look back on our own planet—I would argue probably the most important planet for us."