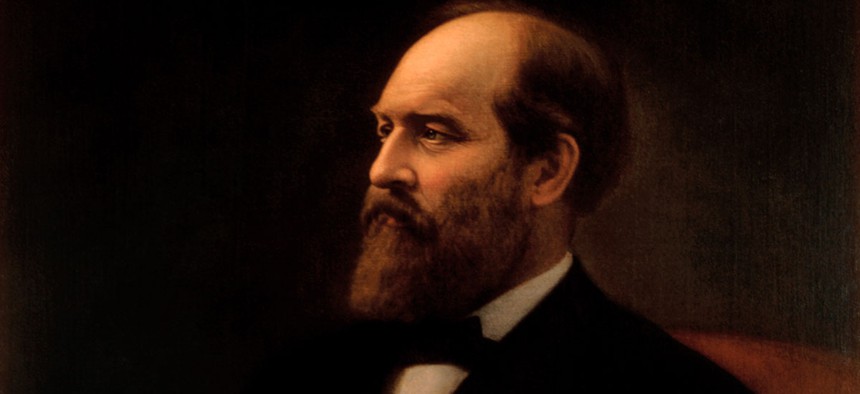

Garfield's White House portrait.

The Man Who Killed a President Over a Political Appointment

Charles Guiteau assassinated James Garfield in 1881. But, why?

Walking into the main exhibit hall of the Mütter museum in Philadelphia is like entering a mausoleum. The remains of the departed are encased in its walls, but instead of marble nameplates obscuring the view, glass panes allow visitors to look in and marvel. Each specimen tells a story of a life not normal: From the skeleton of a man whose muscles turned to bone, to the world’s largest human colon (it looks like a gnarly root of an oak tree), and the attached livers of conjoined twins. All found their way here through donation or because doctors of yore would take souvenirs from their autopsies. I’ve come to check out one specimen in particular.

“These are all my brains,” curator Anna Dhody says, scanning a shelf in the museum’s cellar. We’re in the wet specimen room, a restricted area that resembles a walk-in pantry from hell. Cold like a grocer’s freezer aisle, its shelves are crammed with jars of assorted human viscera shining sickly under fluorescent lighting. “Theoretically he should be here with all my brains,” she says. A few beats pass in silence. “Ahh, here we go.”

Next to a shallow dish of kneecaps, that’s where we find it—“Charlie,” as Dhody calls him. (Ten years curating a museum of medical oddities and you too will be on first-name basis with the specimens, she says.)

In a slender jar, several sections of century-plus-old brain float—like marinated artichokes in a jar—in a solution of 70 percent alcohol and 30 percent water. A label reads: “Portions of brain of Charles Guiteau, assassin of President Garfield.”

The brain of Charles Guiteau is more than an historical oddity. Scientists at the time of his death thought it could unlock a mystery that had plagued and terrorized humanity from the beginning: What separates a normal man who lives by the law from a man motivated senselessly to murder? Guiteau’s murderous act, his apparent insanity, and the ensuing diagnosis of his brain came at a point in history where society was shifting away from the idea of sin being a black and white question, to one where we recognize there’s a great field of gray obscuring these answers.

One hundred thirty years ago, those pieces of gray matter resided in the body of a five-foot-five man with a crooked smile and a damned destiny.

Charles Guiteau, born September 8, 1841 in Freeport Illinois, was, by all accounts, not a stable person. Guiteau bounced around from being a failed lawyer, a charlatan preacher, and a sticky fingered bill collector. He dodged rent his whole life, and subsided mainly from the sympathy of his sister. He abused his wife, and when he wanted to divorce her, he slept with a prostitute to speed up the proceedings. Guiteau was quick to jump on bandwagons, just to abandon them in a fury. Like that time he joined the infamous Oneida community, a utopian-religious (and sex) commune in upstate New York. Guiteau worshipped its leader John Noyes—”I have perfect, entire and absolute confidence in him in all things,” Guiteau wrote of him—before fleeing (twice) and threatening Noyes with blackmail. Guiteau would later plagiarize Noyes’s writings as his own.

By 1875, Guiteau’s father thought his son had been possessed by the devil. His sister’s physician had declared him insane after he threatened her with an axe. Even Noyes—a man who practiced a life of free-love polyamorism, and preached that Jesus had returned to Earth in the year 70 A.D.—later wrote prosecutors that “Guiteau’s insanity had always consisted of vicious and irresponsible habits.”

As he aged, Guiteau increasingly felt the divine dictating his actions. “Like Paul, he had been chosen to preach a new Gospel,” The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau, a 1968 history of the case, explains of his mental state.

Guiteau was crazy by many accounts, but not debilitatingly so. Acquaintances often mistook him for an eccentric. He was able to make it through life without being picked up by police or restrained in asylum.

That was, until 1880, when the voices inside his head led him to the Grand Old Republican party.

)

Before Guiteau murdered Garfield, he was a die-hard supporter. In the lead up to the 1880 election, Guiteau would haunt Republican party offices, begging to contribute to the election effort. He was relentless, and party officials caved and allowed him to deliver one incoherent speech to a small group of black voters in New York City.

The contribution was minimal, but in Guiteau’s mind, “It was this idea that elected General Garfield,” he wrote. And what should be his reward? A cushy European diplomatic post. First, he thought Vienna. No: only Paris would do.

After the election, Guiteau moved to Washington to collect his imagined prize. These were the days when any ordinary citizen could pay visits to officials. Guiteau roamed the halls of the State Department and White House, imploring anyone who would listen that he deserved a diplomatic post.

Meanwhile, he was wasting away. The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau describes his state:

He had no source of income, no lecturing, no books to sell, no bills to collect; he had no family; he never had any friends. His clothes, shabby enough when he reached Washington, were deteriorating. Even in March, with snow on the ground, he went about without boots or an overcoat. By June, his worn sleeves were pulled down over his hands and his coat buttoned up to his neck, for he had no collar and possibly lacked a shirt as well.

The words stung, and set Guiteau off on a bizarre chain of logic which would result in his demise. Blaine was a menace to the Republican party. To get rid of Blaine, he reasoned, he had to kill the president. After all, it was Garfield’s fault that such a man served in the State Department. Guiteau heard these instructions from God himself. It wouldn’t be an assassination, but a divinely ordained “removal.” The plan was essentially motiveless, as the the death of the president wouldn’t stand to benefit Guiteau or any Republican. “In the president’s madness he has wrecked the once grand old Republican party; and for this he dies,” Guiteau wrote in a letter of admission.

After weeks of careful stalking, Guiteau shot Garfield, twice, at the Baltimore and Ohio train depot in D.C. Upon being shot Garfield said “I am a dead man.” He’d lay in agony for 80 more days before that assertion became true.

Guiteau never really had a shot of going free in trial. He was the most hated man in America, and the only person to come to his defense with his brother-in-law, an attorney with very little courtroom experience. During the trial, Guiteau—who served as his own co-counsel—would shout obscenities and broke out into song on one occasion. He also declared “The doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him.” (Which sounded crazy at the time, but actually has some truth to it. “His doctors were ‘the best doctors’ meaning old school,” Dhody explains. “They had trained before the theory of antisepsis, so they were not taking the necessary precautions, they were not sterilizing instruments they were not sterilizing hands.” They also believed a person could be fed rectally, and would give Garfield regular beef broth enemas. Garfield died many pounds thinner and riddled with infection.)

The trial became less about Guiteau’s guilt or innocence, and more of a battleground for the day’s leading mental health researchers to debate a deep, dark question that stretched beyond the sad circumstances of the accused’s life: What was wrong with Guiteau and criminals like him?

The media covered the case in a similar fervor as, many years later, it would the O.J. trial. Each day newspapers would publish transcripts of the proceedings. On the first day of the trial, the courtroom was packed, standing room only, with more waiting outside. This was the biggest stage possible for physicians working in the murky science of the mind. “No single problem divided American psychiatrists more sharply than the proper definition of criminal responsibility,” Rosenberg writes in The Trial.

On trial with Guiteau were two theories of culpability.

The one supported by the prosecution was called the M’naghten test, which stipulated that if the accused simply knew the difference between right and wrong, he could be held accountable for his actions. Guiteau was intelligent enough to know that murder was a crime, and therefore should be sentenced. Maybe it was a life of sin that led him to his consistent erratic behavior, the prosecution admitted. But like an alcoholic taking a first swig, that was on Guiteau. In the mind of John Gray, the superintendent of the Utica State Hospital and the chief medical witness of the prosecution, Guiteau was simply a depraved individual. “I see nothing but a life of moral degradation, moral obliquity, profound selfishness, and disregard for the rights of others,” Gray said at trial. “I see no evidence of insanity, but simply a life swayed by his own passions.”

The defense’s physicians proposed a much more radical theory: That even though some people may know the difference between right and wrong, they aren’t capable of processing reality. Edward Charles Spitzka, a cocky 30-year-old who was a fierce opponent of the M’naghten rule, testified on Guiteau’s behalf.

Spitzka agreed with Gray: Yes, Guiteau had lived an immoral life. But in Spitzka’s view, Guiteau suffered from a mental condition that prevented him from understanding morality in the first place. He called this moral insanity—something we might regard today as sociopathy—which he described as “a person who is born with so defective a nervous organization that he is altogether deprived of that moral sense.”

To Spitzka, Guiteau’s condition was “analogous in that respect to the congenital cripple who is born speechless, or with one leg shorter than the other, or with any other monstrous development, that we now and again see.” These poor souls should be pitied. Throughout the trial, Guiteau believed that the American people and the newly sworn in President Chester Arthur would rally to his side, realizing Guiteau was an instrument of the divine. How is that based in any understanding of reality?

“When people brought up the notion of moral insanity, it was a way of broadening the notion of ‘what is a legitimate illness,’” Rosenberg says on recent phone call. “And it was saying, in effect, that you could be seemingly rational [but still mentally ill]—cognition was not enough of a test of health. Of course to many people that was subversive. It pushed the boundaries of what you could be held responsible for.”

Spitzka believed that this moral insanity was the result of a deformity in Guiteau’s brain, which he likely acquired through heredity. If only doctors could open him up, they’d plainly be able to see the difference.

Doctors did open him up. That is, after he was found guilty and sentenced to hang from a noose until dead. The chance to autopsy an infamous criminal was irresistible to top doctors at the time. “You had all these illustrious, well known physicians, they all wanted to get their hands on his body, because they wanted to be the one who could say ‘hey, this is what did it,’” Dhody says. “They were trying to find any visible, physical reason for why he did what he did.” One of the examiners was a fellow at the college that runs the Mütter museum, which is why “Charlie” is in its collection.

The autopsy didn’t completely vindicate Spitzka’s ideas, but it did lend them some evidence. “Several medical journals, previously hostile to any suggestion that the assassin might have been insane, now reversed their position” after the autopsy, Rosenberg wrote.

The autopsy hinted that Guiteau may have contracted syphilis during one of his encounters with prostitutes. In its later stages, syphilis infects the brain and causes mental instability. “The dura mater that surrounded his brain was thicker than normal, that is sometimes a characteristic of neurosyphilis,” Dhody says. The autopsy also found damage to blood vessels in several areas.

But that diagnosis doesn’t hold up under modern-day scrutiny. George Paulson is the former chair of Neurology at the Ohio State University who, in 2006, reviewed the autopsy records for the journal Historical Neuroscience. Looking back, he says, the evidence for neurosyphilis is inconclusive. “Most people with third stage syphilis—even though they can be grandiose and paranoid and get demented, usually it doesn’t hang on slowly for four or five years,” Paulson says. There’s usually a dramatic loss of cognitive function, he says. Guiteau was crazy for decades. Doctors now could definitely prove whether he had syphilis post-mortem, Paulson says, but not in the 1880s. It’s more likely Guiteau was schizophrenic, with a side of grandiose narcissism.

The law likes hard rules, which mental health avoids. We can all know crazy when we see it, but the line between a culpable mind and an insane one isn’t so easily drawn. These events occurred more than 13 decades ago, but similar dramas play out in courtrooms every year. Who of sound mind could act like James Holmes, who knowingly and without much reason opened fire in a crowded Colorado theater? His insanity plea was rejected by a jury, though he was spared a death sentence. “In a way [diagnosis] makes it simple, but it doesn’t make the social process about ‘what do you do about the guy’ simple,” Rosenberg says.

Guiteau willed his body to a local minister who felt some sympathy for him, on the condition that he would receive a proper burial. Grave robbing, especially of the notorious, wasn’t unprecedented. A secret gravesite was selected in the sub cellar of the Army jail. A 1890 New York Times investigation recalls what happened next. “The body lay there undisturbed for a few days… It had been cemented into its resting place, and the stone flags covered it so that is was profoundly hidden.” But “unknown and mysterious men were constantly prowling around.” Prison officials feared that a guard or convict may exhume Guiteau and sell his body.

So Guiteau’s body was dug up by the authorities in secret. It was boiled in a chemical solution and reduced to a skeleton. “Upon the skull,” the Times recalled, one could still see Guiteau’s “sardonic leer.” The remains were boxed up, “and, without ceremony or fresh service, put away.”

The Mütter museum has another famous brain in it’s collection: Albert Einstein’s. In the main collection room, a slice of his cauliflower-shaped cranial tissue is mounted on a slide under a magnifying glass.

Scientists have been speculating for years what might have been different about it, what clues it holds to the secret of his singular genius. Most apparent was that is showed few signs of the neurodegeneration that come with aging. His autopsy also noted that his brain lacked a sylvian fissure, which may have allowed for increased neurological connections across his mind. But for the most part, it was a normal brain. Even a little lighter than average.

What in the brain separates a man like Einstein from a man like Guiteau is not always possible to discern post-mortem. Genius or psychosis can only be seen in life. “In so many cases, you have these incredibly mentally ill people but the brain is not physically different upon gross examination,” Dhody says. “That’s why studying the brain is much easier to do on living individuals than on dead; a dead brain is a dead brain. It’s static—all the electricity, all the spark is gone.”

I think of that, staring into the glass jar with Guiteau’s brain. It’s just dead matter. The scaffolding of a house, not its contents. I take out my camera and start to take pictures.

“He would have loved this,” Dhody says, as I start, trying to capture his best angles.