Apostolos Mastoris/Shutterstock.com

The Invention of Telecommuting

Working remotely long predated third-wave coffee shops and sleek co-working spaces.

According to the latest Census numbers, 4.5 percent of Americans, or about 6.5 million people, are working from home most of the time. That’s up from 3.2 percent in 2000, and roughly double the proportion in 1980.

This uptick is new, conjuring images of freelancers hunched over laptops—but telecommuting isn’t. The concept of working away from the main office is much older than mobile technology; in fact, it predates the personal computer.

The founding document of telecommuting was a 1973 book called The Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff. Lead author Jack Nilles, a former NASA engineer, proposed telecommuting as an “alternative to transportation”—and an innovative answer to traffic, sprawl, and scarcity of nonrenewable resources.

Research for the book began in 1973, in the midst of a national energy crisis. “Coincidentally, the OPEC oil embargo had begun and the object of our research seemed a little more pertinent nationally,” Nilles told CityLab. Meanwhile, the Clean Air Act had just been passed in 1970. The term “gridlock” entered urban planning parlance, as headlines warned of an impending traffic apocalypse. For years, Americans drove to work in central business districts without a second thought about the environmental consequences. Now, the costs of America’s love affair with the automobile could no longer be ignored.

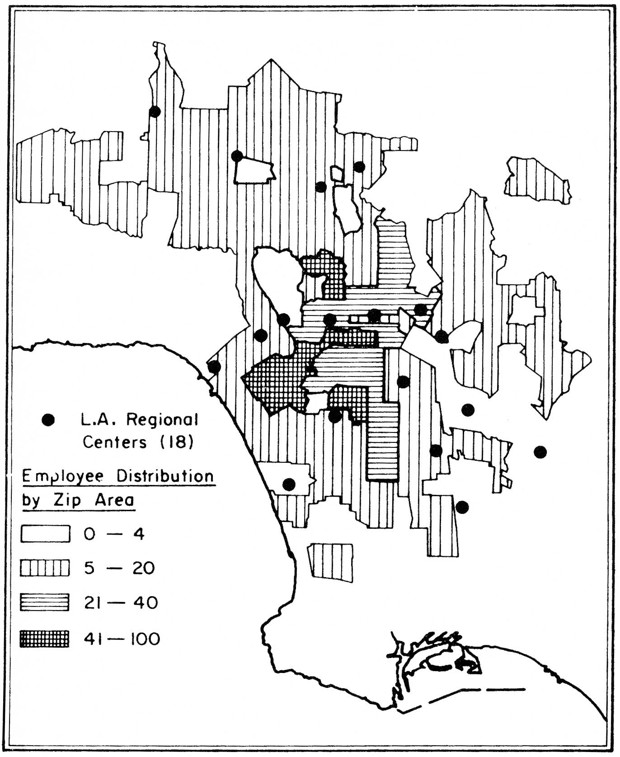

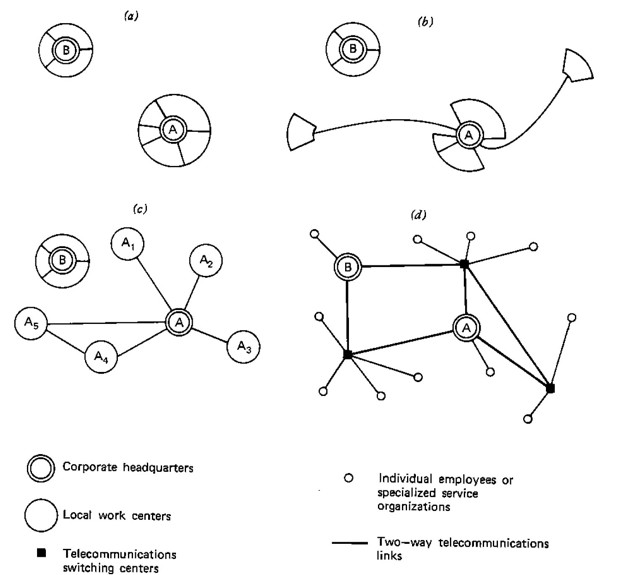

Nilles’s solution to these contemporary concerns was telecommuting, but not quite telecommuting as we know it today—after all, this was before the advent of the Internet. He envisioned firms broken up into satellite offices, where employees could work remotely when they didn’t need to be physically present at headquarters.

Instead of commuting to a central location downtown—and clogging up the area’s already congested streets—clerical workers would report to whichever office was closest to their homes to receive and complete assignments there. “Our primary interest, and the greatest impact on traffic and energy consumption, was reducing the commute to work,” Nilles says.

The authors wrote that “either the jobs of the employees must be redesigned so that they can still be self-contained at each individual location, or a sufficiently sophisticated telecommunications and information storage system must be developed to allow the information transfer to occur as effectively as if the employees were centrally collocated.” We know, with the benefit of hindsight, that both changes took place.

The Internet and the personal computer transformed the workplace, creating new jobs while rendering others obsolete. Nilles’ team predicted this, noting that new technologies “have the potential for acting as catalysts that could radically change the structure of American society in much the same way that the automobile acted as a catalyst on our way of life during the first half of this century.”

But way back in 1973, they couldn’t see exactly was coming—and some of their loftier projections for the impact of telecommuting reflect that. In a chapter on the indirect impacts of telecommuting, the authors posited:

“With a decrease in commuting time and distance individuals would be able to spend more time with their families and friends and use healthier means of getting to work, such as bicycling and walking.”

The number of Americans walking and biking to work has increased in recent years, and telework can increase job satisfaction and employee loyalty in some cases. But working from home also erodes the barrier between work and life on the whole, obligating employees to stay connected and available at all times. That “always on” mentality can take a toll on worker health as well as business outcomes. But some hold out hope that this flexibility can benefit working moms and even help to close the tech gender gap. Nilles and company:

“The existence of local offices could, with the schedule flexibility afforded by interactive computer networks, allow much more part-time job mobility, as discussed earlier. A reduction in human frustration with traffic congestion could have beneficial effects not only on the temperament of employees but also on their productivity.”

Jobs have become more mobile, but they’ve also become more unstable. Just look at the ongoing court battles over worker’s rights in today’s so-called “gig economy.”

The authors of The Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoffacknowledged even then that some of these notions were “quite speculative.” But they were right on a number of crucial points, anticipating the rise of mixed-use developments—which they called “rural cities”—and the political difficulty of building new transit systems. The team’s forecasts for the future of computing were “rosy” and “right in general,” Nilles says. Indeed, the book opens with a visionary look at E.M. Forster’s science fiction story “The Machine Stops,” in which human life is sustained by a vast telecommunications machine. “At the time the story was written,” the authors note, “such technological wonders were fantasy; today, they are becoming accepted as commonplace by many Americans.”

Nilles realized early on that “technology was not the limiting factor in the acceptance of telecommuting.” Instead, he says, “organizational—and management—cultural changes were far more important in the rate of acceptance of telecommuting. That was the case in 1974 and is still the case today. The adoption of telework is still well behind its potential.”

Some studies have shown that telecommuting can contribute to a significant reduction in vehicle miles traveled—and, consequently, in greenhouse gas emissions. But it’s difficult to quantify the effects on traffic and energy usage, the forces that directly inspired Nilles’ book.

Whatever the ultimate impacts of telecommuting, the authors were right in recognizing the need for action. “Until the early 1970s, the United States’ economy was operating as if expansion of the automobile industry and increasing dependence on the automobile were destined to be continued indefinitely,” they wrote. But the Arab oil embargo and ensuing energy crisis exposed America’s dependence on finite oil reserves. Forty years later, their words still ring true:

We are now at a decision point as a society; we must decide whether the way of life made possible by the automobile since the turn of the century will (or can) continue, or if we should consider alternate or modified modes of working, communicating, and living.

(Top image via Apostolos Mastoris/Shutterstock.com)

NEXT STORY: The False Promise of Meritocracy