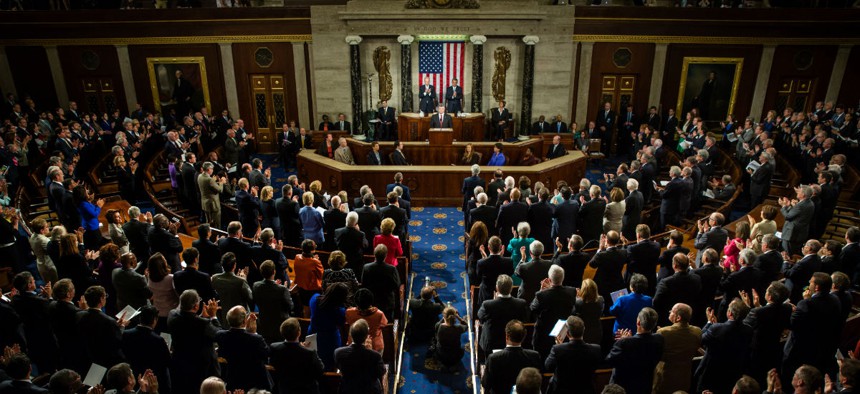

A joint session of the Senate and House of Representatives in 2014. Drop of Light/Shutterstock.com

Hidden In the Partisan Budget Divide: An Agreement on Evidence-Based Policy

So far, much of this has flown below the radar.

Presidential budgets are often greeted with little enthusiasm when Congress is controlled by the opposite party. This year's Obama budget is no exception. But buried within the president's $4.15 trillion budget are recommendations on evidence-based policymaking that may prove more influential than some expect.

This may not be readily apparent from the initial reactions on Capitol Hill. House Speaker Paul Ryan called the president’s budget "a progressive manual for growing the federal government at the expense of hard-working Americans."

In a significant departure from past practice, congressional Republicans declined to invite OMB Director Shaun Donovan to explain the president's proposals. Instead, Ryan is working to quell a rebellion among House conservatives who want to roll back a modest spending increase that was previously negotiated by former Speaker John Boehner.

Given the escalating partisanship in Congress, the president’s budget might seem not just dead on arrival, but completely buried. Those sentiments, however, are not shared by administration officials.

"The conventional wisdom is wrong," Donovan told The Washington Post. “We think there are a lot of proposals that can get bipartisan support.”

So what might those be? One possible area of agreement is evidence-based policy, a wonky bucket of issues that includes rigorous evaluations of federal programs, expanding the use of administrative data, and steering a greater share of federal funding to programs with strong evidence of success.

So far, much of this work has flown below the radar. The House passed legislation that would create an Evidence-based Policymaking Commission last year and the Senate is poised to pass it in the coming weeks. Evidence-based policy also played a substantial role in a major K-12 education bill that was enacted at the end of last year.

This progress may also continue in the coming year. Ryan has signaled that he wants the House to pass a legislative agenda that would articulate a larger Republican vision for government. In recent days, he has set up six legislative task forces on taxes, national security, regulatory reform, health care, congressional-executive branch relations, and addressing poverty.

The last of these may substantially advance evidence-based policymaking all by itself. Ryan has called for changes that he says would both give states and local communities greater flexibility to innovate while simultaneously subjecting their innovations to rigorous evaluation. Ryan doubled down on the issue as recently as last month, when he hosted a poverty forum that was attended by most of the Republican presidential candidates.

The Obama administration seems willing to meet him halfway. There is some agreement between them on expanding the earned income tax credit, a tax subsidy for low-income workers, although they have not yet agreed on how to pay for it. Any final deal, if it occurred, would probably tap at least some of the president’s evidence ideas.

Nicole Truhe, government affairs director for America Forward, a coalition of results-oriented nonprofit organizations, says there are also other evidence-based proposals in the president’s budget that command bipartisan support, including high quality pre-school programs, home visiting, and programs to end veteran homelessness.

She also points to several low- or no-cost proposals, including consolidating existing evaluation funding streams, expanding the use of administrative data, and increasing the transparency and relevance of federal research clearinghouses.

Her optimism is not shared by everyone, however. "The president is obviously looking for a fight," said David Muhlhausen, a research fellow for the conservative Heritage Foundation who specializes in evidence-based policy. "When he puts forward these huge spending increases, it poisons everything to such a high degree that there is no way any Republican could agree."

Jeremy Ayers, vice president for policy at Results for America, an organization that supports the increased use of evidence in government, has a different view.

"Picking which problems to solve is a political decision," he said, "but data and evidence are the tools policymakers should use to solve those problems. That's why evidence is ultimately a bipartisan solution that deserves more support."

Will such bipartisanship materialize? Perhaps, but it may be as much about the low profile of these issues as anything else.

Evidence, data, and increased government efficiency rarely elicit much attention among diehard partisans. As Congress enters an election year, that may turn out to be their biggest strength.

Patrick Lester is the director of the Social Innovation Research Center.

(Image via Drop of Light/Shutterstock.com)