Then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton arrives in Melbourne, Australia in November 2010. State Department file photo

What Feds Thought About the Clinton Team's Honesty, Leadership at the State Department

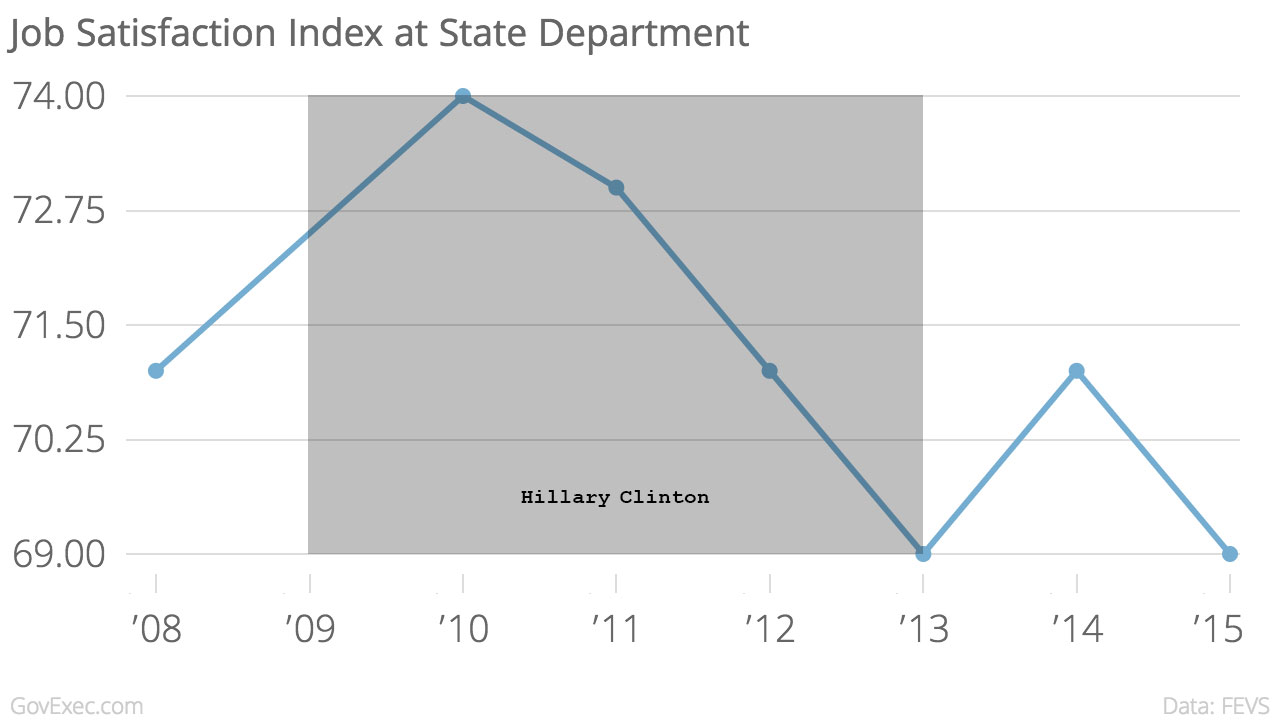

A review of employee viewpoint surveys shows employees were generally happy with how the department was managed under Clinton, with a slight decline toward the end.

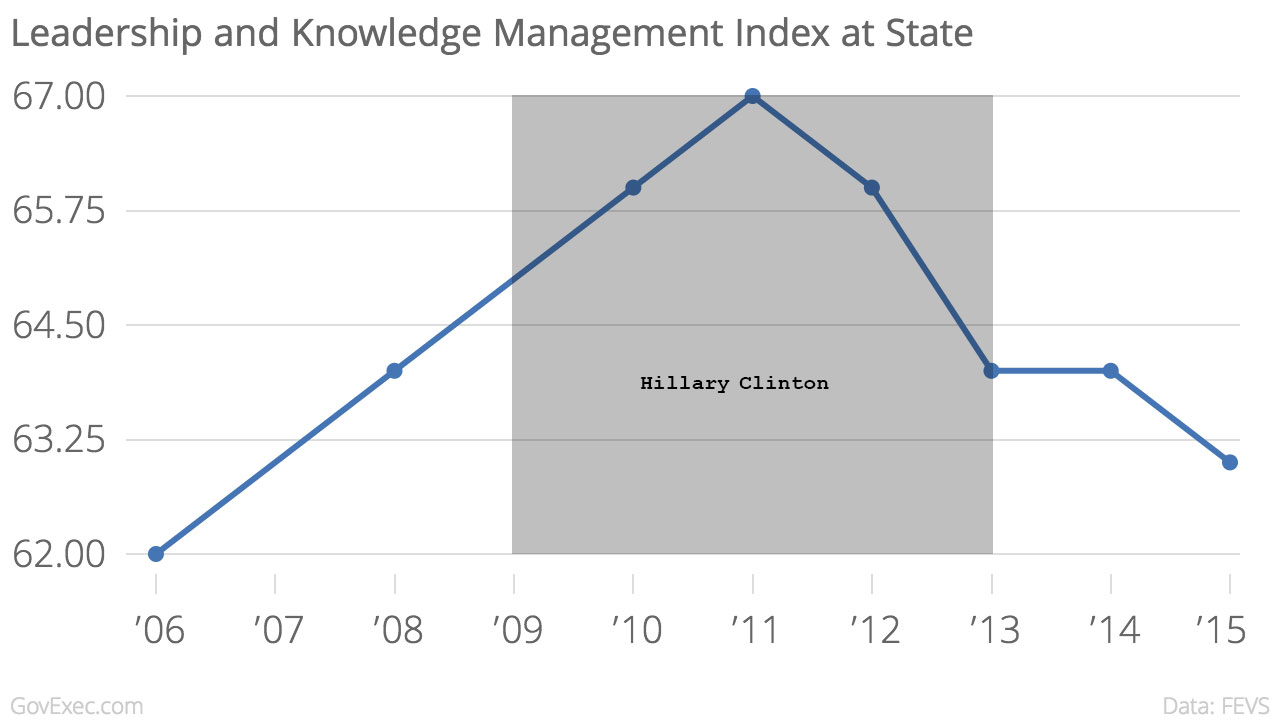

Ask Americans today to evaluate Hillary Clinton’s time as secretary of State and you’re apt to get answers colored by their attitudes on whether she deserves the presidency. But a look at contemporaneous federal employee survey results and specialty groups’ assessments from 2009-2012 offers a glimpse of a Clinton tenure that began with great promise and then faded slightly, though the department consistently ranked highly compared with the rest of government on a range of leadership and management measures.

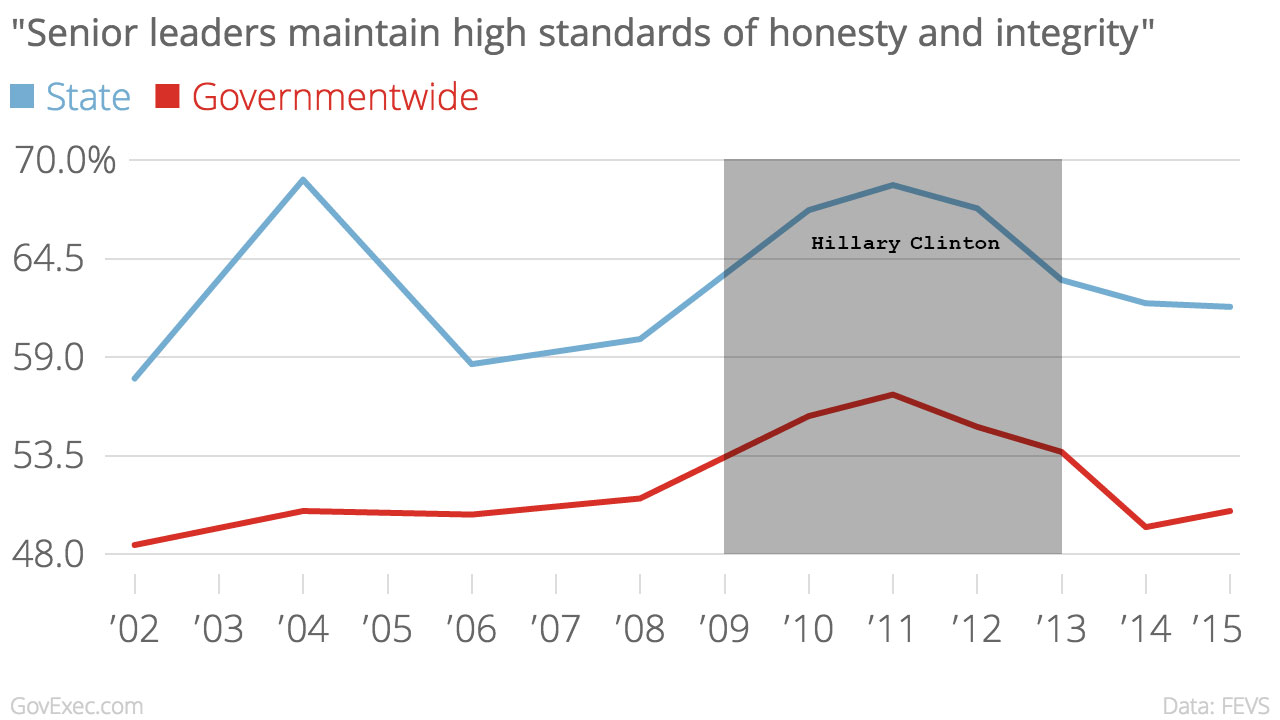

A Government Executive review of State Department responses to the Office of Personnel Management’s annual Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey shows that Clinton in her first two years managed to raise the rank-and-file appreciation for leadership in such areas as whether the agency was succeeding in its mission. Somewhat surprisingly, given national polls showing distrust of Clinton’s ethics among many voters, department employees under Clinton agreed that their leaders conducted themselves with honesty and integrity at higher rates than federal employees governmentwide. (The survey did not specifically ask about Clinton, but rather about leaders in general).

The State Department’s’s approval numbers dipped, however, in Clinton’s final year, particularly in such categories as job satisfaction and satisfaction with leadership’s policies and practices, perhaps a reflection of budget cuts and the still-controversial deaths of four Americans in 2012 in the U.S. compound in Benghazi, Libya.

As a prelude to reviewing Federal Employee Viewpoint surveys from Clinton’s time in office, Government Executive sought an analytical assessment by qualified State Department observers.

Clinton won highly positive commentary in the Foreign Affairs Council’s June 2011 task force report titled, “Managing Secretary Clinton’s State Department: An Independent Assessment.” Written by a committee summarizing the views of 11 foreign policy and diplomatic associations concerned about budget cuts, the assessment “documents dramatic progress on a variety of managerial fronts,” during Clinton’s first two years. “Secretary Clinton has energetically and appropriately pressed for the resources necessary to give the United States the civilian tools it needs for conducting foreign relations in the 21st century,” the diplomats wrote.

There was more effusion after the department under Clinton created a Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review. Among other recommendations, the review -- begun in 2009 and released at the end of 2010 -- stressed the need to give chiefs of mission at embassies “the tools they need to oversee the work of all U.S. government agencies working in their host country.” And it committed the U.S. Agency for International Development to becoming the government’s leading development agency.

The Foreign Affairs Council “believes this first QDDR and its reforms and recommendations together represent the most significant management initiatives in the operation of the Department of State and USAID in many decades,” the report said, adding that much would depend on Congress and future follow-through. “The secretary and her team will be required to demonstrate the strong leadership and stamina that has characterized Secretary Clinton’s leadership thus far. This leadership and her concern for the institution and its people have won their respect and buttressed their morale.”

Retired Ambassador Thomas Boyatt, who was lead writer on the Foreign Affairs Council assessment, told Government Executive: “The problem is every secretary has to do two things -- manage foreign policy and manage the institution. As manager of the institution, I’d say, [Clinton] was a failure. She didn’t manage it, which is not an unusual style for a secretary of State. She turned it over to her longtime retainers, and while she was flying around the world doing the foreign policy management, the people management was deteriorating.”

Clinton’s top deputies “were not there long enough to learn how things operate,” added Boyatt, who briefly served as president of the American Foreign Service Association 46 years ago. “The overall structure was that her personal aides, such as Cheryl Mills and Huma Abedin, had positions of authority in the State Department and could intervene in personnel and other matters on behalf of the secretary. That was not always in the national interest, but in the interest of the secretary of State.”

Clinton herself, in her 2014 memoir of State Department life titled “Hard Choices,” wrote, “When I became secretary, the career professionals at State and USAID had been facing shrinking budgets and growing demands, and they were eager for leadership that championed the important work they did. I wanted to be that leader. To do so, I would need a senior team that shared my values and was relentlessly focused on getting results.”

She went on to describe the promise she obtained from the White House to be able to select her team. On Mills, her counselor and chief of staff, Clinton said: “She helped me manage ‘the Building,’ which is what everyone at State calls the bureaucracy, and directly oversaw some of my key priorities, including food security, global health policy, LGBT rights and Haiti. She also acted as my principal liaison to the White House on sensitive matters, including personnel issues.”

Compared with other large departments, State under Clinton fared well in agency rankings in the Federal Employee Viewpoint survey. The survey’s methodology provides an inexact measure of a secretary, given that Clinton’s name is never mentioned in the survey questions. But FEVS did ask specific questions about department “leaders” and “senior leaders,” providing insight into employees’ views on Clinton and the team she assembled.

In 2011, the survey ranked the State Department third in job satisfaction among 37 large agencies, sixth in leadership and knowledge management and seventh in talent management.

Based on that assessment, the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service ranked State third among large agencies (behind NASA and the Intelligence Community) on its “Best Places to Work in the Federal Government” list, a slight drop since 2011.

State’s scores were above the large agency median in all the “Best Places” studies from 2009-2013, Mallory Barg Bulman, director of research and evaluation at the Partnership, told Government Executive. In the category of effective leadership, “once again the entire time she’s there, the score is higher than the large agency median,” Bulman said.

Employees responding to the survey distinguish senior leadership from their own supervisors, Bulman noted, and tend to rank their own supervisors higher. “But for the State Department during Clinton’s tenure, senior leaders were ranked in the top quarter and higher than the median.”

In the Federal Viewpoint survey’s specialized indices, State in 2012 ranked sixth among large agencies for leadership and knowledge management. Its approval in that area rose from a score of 62 out of 100 in 2006 to 64 in 2008 to 66 in 2010 to 67 in 2011, before ticking down to 66 in 2012.

In the survey’s talent management index, State in 2012 ranked ninth among 37 large agencies, and its score rose slightly from 65 in 2008 to 66 in 2010, before dipping to 65 in 2011 and to 63 in 2012.

On individual questions, Clinton’s employees were most enthusiastic on the question, “My agency is successful at accomplishing its mission.” Eighty-one percent of respondents either strongly agreed or agreed in 2010. That rose to 84.3 percent in 2011, dipping to 82.5 percent in 2012.

The same pattern of an initial rise shows up in the question, “I have a high level of respect for my organization’s senior leader.” Employees who strongly agreed or agreed rose from 64.9 percent in 2010 to 67.5 percent in 2011, before dropping again to 64.7 percent in 2012.

Perhaps the most important question in the survey’s measure of employee views of top State Department leadership under Clinton, given the recent debate over her decision to use a private email server for work and her overall trustworthiness as a presidential candidate, is: “My organization’s leaders maintain high standards of honesty and integrity.”

But respondents to the honesty question at the time she was in office gave her leadership team high marks. Those who strongly agreed or agreed leaders were honest rose from 67.2 percent in 2010, to 68.6 in 2011, dipping to 67.3 in 2012 and 63.3 percent in 2013, when Clinton left office.

Those percentages, too, were consistently higher than governmentwide numbers over the past decade, often by more than 10 points.

Amelia Gruber and Ross Gianfortune contributed to this article.

This story was amended to add context to Boyatt's position as president of AFSA in 1975. AFSA does not comment on political matters.